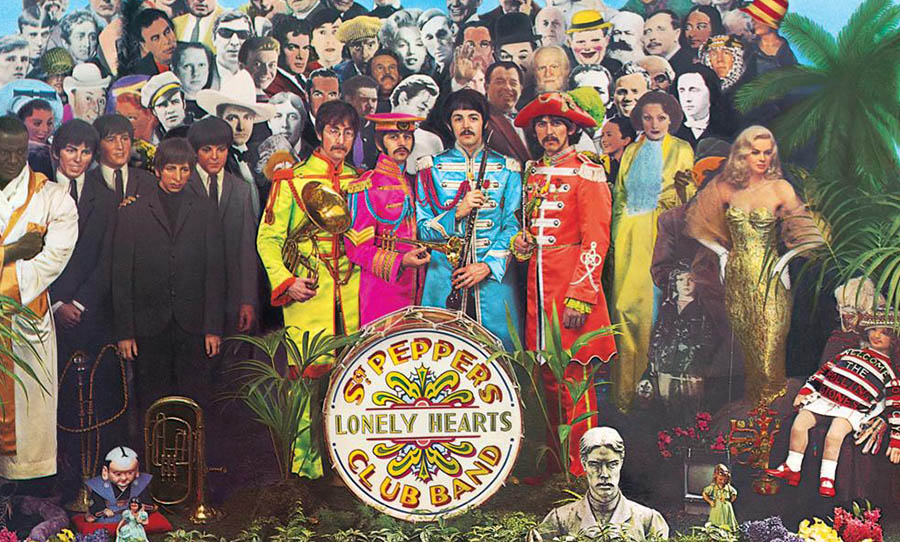

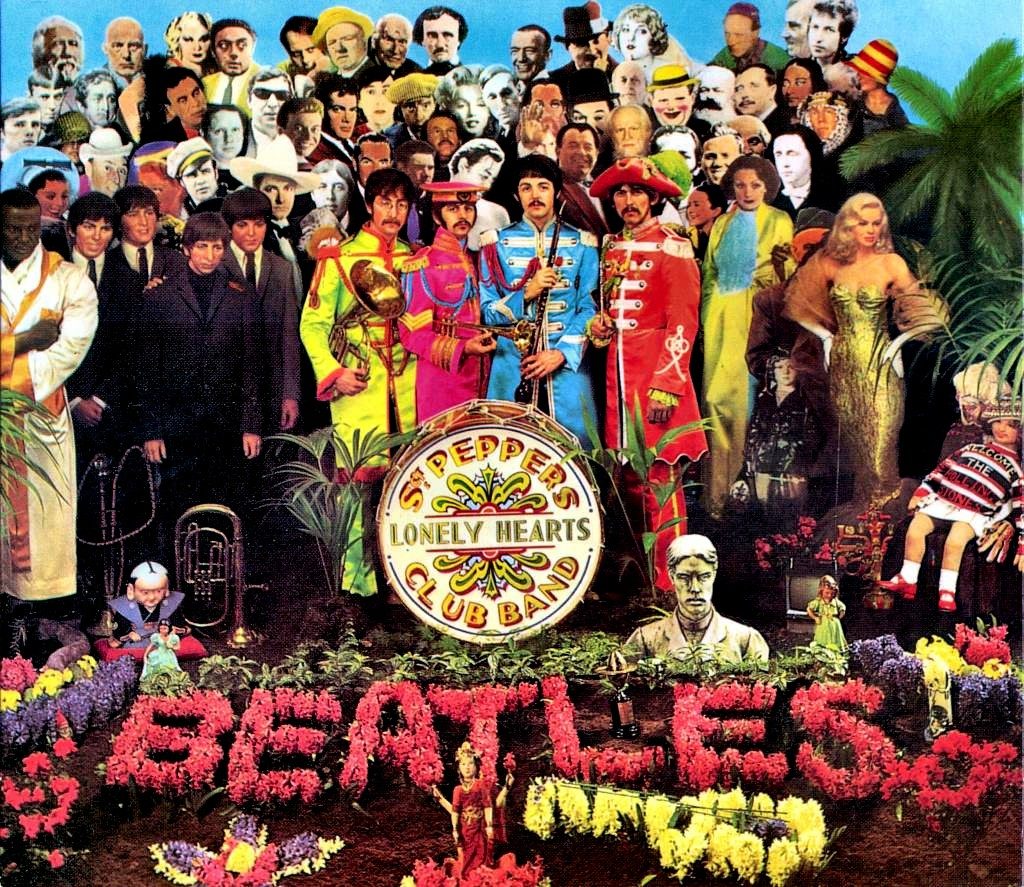

Riding in on the crest of a wave of counterculture, rock idealism and recording innovation Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band broke ground in nearly every direction. Nearly half a century since its release, audiophiles and fans alike still venerate The Beatles’ eighth record as one of the greatest albums of all time.

Yet it wasn’t just the Fab Four and George Martin who were present at the marathon sessions in which the album was created. Amongst those assisting the star talents was 19-year-old sound engineer Richard Lush.

From 1965 onward, Lush would assist in the recording of 55 Beatles’ tracks and participate in 100 recording sessions with the iconic Liverpudlians.

Following his stint at Abbey Road Lush relocated to Sydney in the mid-70s. Here he would work with the likes of Sherbet and Air Supply, creating a series of international hits which helped define an emerging Australian sound.

Ahead of one-of-a-kind Beatles Q&A The Masters of Sgt. Pepper we caught up with the veteran recordist to gain insight into the studio practices of the Fab Four, recording solo with John Lennon and his later career down under.

Almost half a century ago Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released. Richard Lush was one of the 9 people on the planet behind the scenes.

HAPPY: You kicked off your recording career at Abbey Road Studios as a tape op…

RICHARD: I did indeed. That was basically my job when I started. Like all the jobs there you did it for a period of time then you were promoted. The normal path was to go on to cutting to what is now known as mastering. So once you learnt how to record everything you then went on cutting and then you went on to balance engineer or recording engineer. But I didn’t make that jump; I went straight from a tape op to being an engineer!

HAPPY: It sounds like a very labour intensive job to start out in…

RICHARD: It was. The hours, working with The Beatles for instance, were very long! 12-14 hour days, we worked bloody hard!

HAPPY: I’ve read that first time you crossed paths with The Beatles was assisting with the recording of Paperback Writer in 1965…

RICHARD: It could well have been. I remember that Paperback Writer was the first time I met [The Beatles’ famed Svengali manager] Brian Epstein. He came in on that session to hear the track.

HAPPY: What were some of your first impressions of the band?

RICHARD: Well I guess the first impressions were that they would try different things, especially John. At the time the process with other bands was more like a live performance. They would come in play their song to a producer and then go in and record. An hour and a half later it would be finished. The Beatles used to layer things and, basically from Revolver onwards, would do things which would have been impossible for them to play on stage live. I mean there were half-speed pianos, guitars and voices run through Leslie speakers as well as all these backward recordings. They were always after something unusual.

HAPPY: In terms of songwriting, did you have a favourite Beatle?

RICHARD: Oh gosh! Not really! I mean George had his moments, I quite liked the innocence of George in a way. He was a very kind person, he was very thoughtful. John and Paul… They both had good points and bad points!

HAPPY: It’s been nearly 50 years since Sgt. Pepper’s was first released. What is it about the album which has continued to resonate with music fans after all these years?

RICHARD: I think, hopefully, that all the hours spent on it really extracted everything out of each song. We made a point of making each song different. It’s not a kind of a typical album. It’s not like, let’s just say, a Crosby Stills and Nash album. Most of their songs have… not a similar feel necessarily, but you can kind of listen and go: “Oh, that’s Crosby Stills and Nash!”

With Sgt. Pepper’s all the songs were so different! You couldn’t just pick it straight away as The Beatles. But then again you might have to ask kids today who are 16. What do they like? They’ll probably like Help! or the other older stuff that was all done very quickly (laughs). My Daughter has never gotten into The Beatles for some reason…

HAPPY: She hasn’t!?

RICHARD: Maybe they’ll get there at some stage. But she did have a dinner party a while back and wanted to play all my records. She’s having all these people over for dinner and there’s all this Sinatra and Simon and Garfunkel playing.

HAPPY: People are always coming back to that period of music. What is it do you think that draws them there?

RICHARD: Well it was such a great period. Many, many people far wiser than me have labelled it as a golden period. When rock and roll started it was new! It was a whole new scenario. We’d gone from classical music to big bands and then to Sinatra and people like that. Then rock and roll: Gene Vincent, Buddy Holly and Elvis. A whole new world opened up. Whereas now we’ve had rock and roll for 60 years!

HAPPY: It’s kind of in a holding pattern…

RICHARD: Everything is repeated now. Back then it was new and exciting, certainly for us making the records. When we finished them we thought: ‘Wow, I can’t wait for people to hear this!’ Especially with things like A Day in the Life! Everybody was so proud of that song. We thought that it was something people were really not going to expect.

HAPPY: It sounds like you were really gelling with what The Beatles were doing. Their most iconic albums came out during the height of psychedelia and ‘60s counterculture. These movements were really shaking things up in London and other areas of the world. Was it affecting you as an engineer?

RICHARD: Well, I didn’t go around in bright red trousers or dye my hair, but we were definitely influenced by The Beatles. Even the little things like the fact that they dressed differently to everybody else, especially John! When you saw the rest of the bands that came in to the studios they were pretty straight in comparison.

Consequently, we looked pretty straight too! George Martin looked especially straight, he always had a tie and shirt and suit. Every now and again he’d take his tie off and we go like “Wow! Gosh! What’s going on here?” They were funny times; we had a lot of fun too.

HAPPY: You continued to work with the members of The Beatles on a number of solo albums. You worked on, John Lennon’s initial solo album, Plastic Ono Band….

RICHARD: The very first Lennon solo album was very interesting. I’d already worked with [producer] Phil Spector on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. We had some fabulous sessions; I mean Billy Preston came in to play the piano on God; we had both John and Billy playing piano! The fabulous Ringo was on drums and Klaus Voorman was on bass. It was a great little unit! Phil Spector was his inimitable self, pulling the strings, and Yoko was there nodding her head along too.

There were some extremely funny moments and some good songs. It really was John speaking from the heart. He didn’t want the huge Phil Spector ‘wall of sound’ on everything; he wanted it to be pretty straightforward. It was good, we didn’t end up doing hundreds and hundreds of takes, which is probably what would have happened if Spector had had his way!

HAPPY: The dynamic between John and Phil! Both had such big personalities.

RICHARD: Oh yes! I guess they were both… one could call them ‘out there in their own way.’ They were great sessions, the total opposite of George Martin.

HAPPY: During the mid-1970s you relocated to Australia to work as a producer at EMI studios in Sydney. Here you worked with bands like Sherbet and Air Supply on some of their biggest international hits. What prompted you to move?

RICHARD: Well it’s funny you should ask. We had a noticeboard at Abbey Road and somebody put a note up saying ‘Engineers Wanted in Australia’. I wish I still had a copy of it! Everybody laughed; you know they thought “Oh my god. Who wants to go all that way?” Me included. So I went home and said to my mother, who I lived with at the time, “they’re looking for an engineer in Australia.” It was her who half-talked me into it; she regretted it because I didn’t come back!

HAPPY: You were still quite young at this point?

RICHARD: I was 24, but I had worked with quite a few Australians. Bruce Welch from The Shadows, his girlfriend was Olivia Newton-John at the time, so I’d worked with her. I did some stuff with The Masters Apprentices at Abbey Road too.

I came to Australia for two years at first, then went back to Abbey Road but didn’t last that much long back in good Old Blighty. The weather was driving me crazy so I came back. Fortunately, my job was still here at EMI. I left EMI in 1980 and went to work with Billy Fields at Paradise Studios, did the Bad Habits record and then went freelance…

HAPPY: The ‘70s and ‘80s were a big period in Australian music. In a sense, Australia’s music found its identity. Artists started to become recognised on a bigger scale, most importantly by those living outside of the country. Beforehand the most successful local bands would leave the country for UK or the US. Most would come back with their tail between their legs. What was it like during that time? Was it an exciting period for you being behind the scenes?

RICHARD: It was because people, Sherbet particularly, wanted to use me to record. Summer Love was the first record I did with them. I had briefly gone back to England by the time it got out and received these letters from Roger Davies, their manager, saying: “It’s gone to number #1! Come back!” I did, in fact, come back and the year later we did the Howzat album.

It was interesting in the sense that at that time LRB [Little River Band] were using an American producer to do their records in Melbourne. They had a guy called John Boylan who was from LA and very cool. So he was there, I was doing Sherbert in Sydney and also there was Ross Wilson producing The Skyhooks. We were kind of these three people doing most of the records in the country at that time. It was all very friendly, that was one thing that didn’t happen in London! You never met anybody else from the studios. It was a weird situation having Decca Studios just down the road from Abbey Road but never meeting anyone from there! In Australia it was more casual, it was good! You saw other bands too, EMI had two studios. We’d be in one studio and the Divinyls would be in another. It was a really good vibe.

HAPPY: You’re co-hosting a Q&A for The Masters of Sgt. Pepper, a one-off multimedia event celebrating the release of Sgt. Pepper’s, with fellow Pepper engineer Geoff Emerick in February. Is there anything you can share with fans ahead of the event?

RICHARD: Well gosh I’m not sure what they’re expecting or what we’re going to say! We haven’t got secret recordings or anything like that. We were good boys back then. We never slipped outtakes the band didn’t end up using into our pockets. Geoff’s career went in another direction. He’s mainly known for The Beatles but he’s also recorded with Jeff Beck, Art Garfunkel, America and goodness knows who else. So he’s got thousands of stories. Hopefully, we’ll get to go through some of those too.

But the main thing is for people to hear what it was like doing stuff behind the scenes. I mean there are books out there that explain what we did, but they’re all kind of second-hand knowledge. Unfortunately there used to nine people that were privy to what went on when we recorded the album: The four Beatles, George Martin, Geoff, myself and two road managers. Two Beatles are gone, George Martin is gone and the Road managers are gone now too. There’s only Paul, Ringo, Geoff and I left now, which is a bit sad really. There are not many people left to tell the story, it’s a bit poignant when you think about it like that.

HAPPY: But is it heartening in the sense that these days people, both producers and fans, really do want to know about all this behind the scenes information?

RICHARD: It is. When I first started EMI had a policy in England that engineers shouldn’t be credited on the label’s records. We used to see records in America where both the engineer and studio had been credited. When Pepper came out the cover just read “produced by G.H. Martin”. We’d spent all that time and were a bit miffed! It wasn’t until the album came out 20 years later as a CD that we actually had proper credit. It’s good nowadays, although now we’ve got people who download records! You download something and it’s hard to tell who played what on them!

HAPPY: Liner notes are going the way of the way of the dodo in the digital age! It’s a big issue in some areas of the industry.

RICHARD: I hope that people are interested. I meet quite a few young people and they are interested in what went on. We did a fun project in London about 10 years ago now; 40 Years of Pepper. Bob Geldof had the idea that we recorded today’s bands singing the songs of the album on a four-track. Geoff and I went over and it was the funniest experience. Well, Geoff found it frustrating when he found out that people sang separately, they never sang their harmonies together!

So we made them stand there, learn them and then sing them all together. We put the bands under a bit of pressure, but I think in every case it made a better version of the song. They were so used to playing three average versions then having someone chop it all up and edit it where something wasn’t perfect. Here they had to do it in a day! A lot of the bands came up at the end and thanked us, they’d learnt a lot from the process.

All the details for The Masters of Sgt. Pepper can be found on the Facebook event, but the basics are below:

February 24 and 25 – Planetshakers Centre, Victoria – Tickets