Exploring the revolutionary sounds and technology that defined the golden era of rock and roll: the ’50s.

Following World War II, there was a disruptive opening in democracy during the ’50s which cried to be filled with the burgeoning rights of all men. But how does one start a revolution? Often the subtlest, most easily digestible forms of rebellion are in art.

Music can sound revolutions before they begin; can syncopate heartbeats in their heavy vibrations before the song even ends. The sounds made in the ’50s, by new instruments and techniques, were a tearing up of different parts of traditional musical genres – rhythm and blues, and country and western – and the sewing together of a new one, rock and roll; although it was hard to see where the seams lined up, and what parts had been lost or transformed altogether.

Rock and roll screamed over the old order until it was sung and enjoyed by both black and white people in America, and then worldwide.

The Sound That Noise Makes

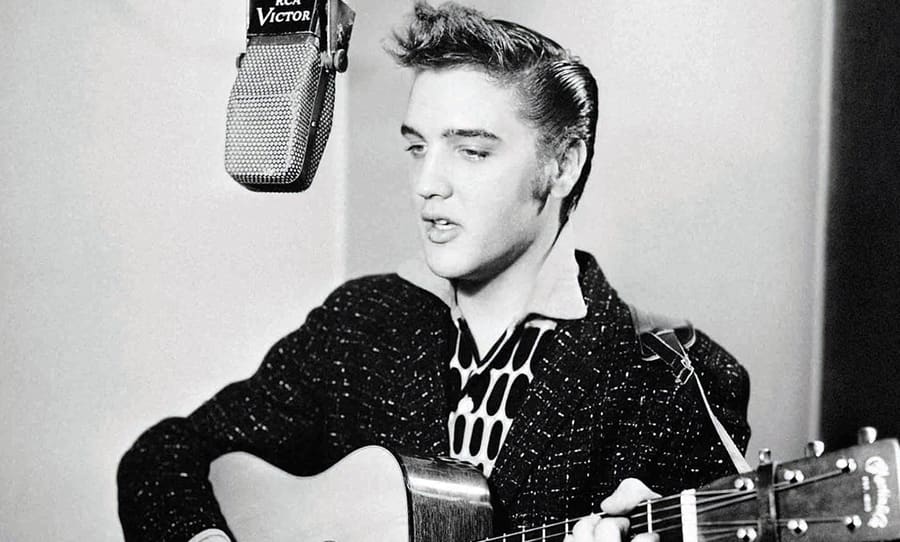

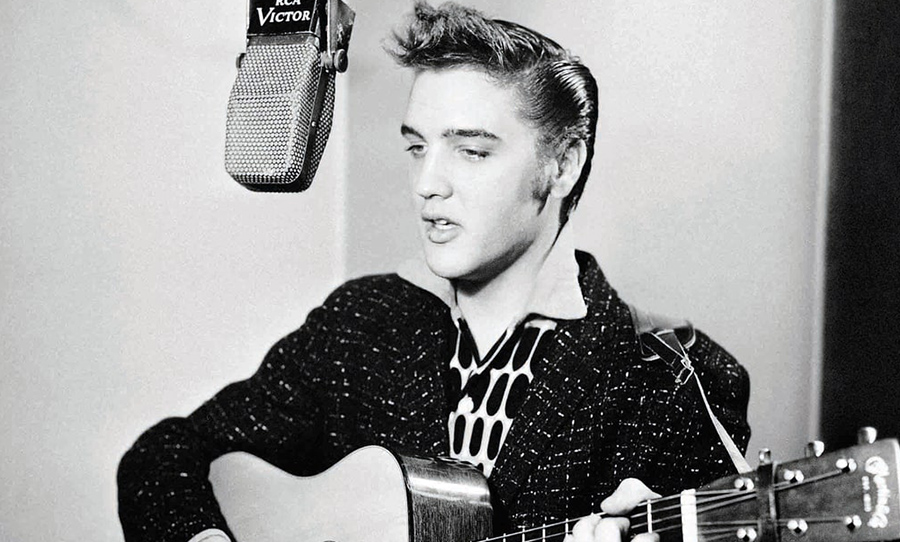

It might be intuitive to say that a new sound can cause a ruckus. Sometimes a sound can be so shocking that it can irk people into change. When Elvis Presley’s That’s Alright (1954) was recorded, the sound seemed so new, that it made people feel and think differently. Like, they didn’t know this kind of sound could exist. It reflected a something that the American youth were trying to express, but couldn’t quite figure out how to do so.

A big part of Elvis’s rockabilly sound was the slapback echo (72-250 ms). The sound decayed quickly, had short time delay and no feedback, creating the feeling of space and a wide open room.

The effect was first devised by Sam Phillips of Sun Studios in Memphis by feeding a signal through two alternate tape machines. Phillips wanted to evoke the atmosphere of live music, and at the same time reflected the rawness of the slowly-developing rock and roll movement. The echo stretched out the music so that it could be softened and loosened, while also being syncopated and intense.

This opened up a gulf of anxiety in the lack of an easy definition for rockabilly itself; with the quality of rhythm and blues, but the rhythmic and lyrical styles of country and western. What this really was, was a lack of definition between black and white music; a new questioning of what was popular. Sam Phillips used slapback echo in his recordings in a way that purposefully blurred racial lines. He recruited Elvis in his production, as the white provocateur of black music.

This sense of space was emulated later in the decade with the wet, splashy sounds of a spring reverb, fundamental in surf music. The vibrations are made as the sound moves through a spring, creating feelings of the breadth, depth and noise of the ocean.

Play it Loud and Clear

The solid-body electric guitar was the centrepiece around which rock and roll was encased. The instrument was radical because it changed the format of the band. The increase in volume of the guitar gave the player an entire band in his two hands. It was made by one solid piece of wood and used a magnetic pickup to amplify only the string vibration, removing the undesirable feedback and distortion present in hollow-bodied electric guitars when the volume was turned up.

There was a newfound freedom in the guitarist’s ability to shape the sound before it reached the amplifier too, with tone and volume controls ever within reach. The formula for a band was no longer written. The brash, gritty, simple guitar could stand alone, and the brash, gritty, simple guitarist could lead the ensemble.

These new designs were first mass produced in the forms of the Fender Telecaster (1951), the Gibson Les Paul (1952) and the Fender Stratocaster (1954). They were relatively cheap and were therefore purchased by many young people, who subsumed the guitars into their culture, as a way to emulate their new idols.

The Telecaster pioneered new cost-effective features, such as the bolt-on neck, relying heavily on functionality in its simple construction and aesthetic. It is a slim guitar with a single cutaway design, one volume and one tone dial, and a three-way pickup switch. This inherently ‘American’ machine was durable and easily repairable. By altering the tone and switching between the dual pickups on the guitar, it’s possible to get two divorced sounds: a bright, twangy country-style tone, and a deep, warm jazz sound. As such, it was consumed by both country and rockabilly artists.

Gibson’s response to the Telecaster was the Les Paul (1952), which had a warmer, heavier tone. Still utilitarian in design, it has two dials for volume and tone respectively, and a three-way pickup toggle.

Fender’s 1954 Stratocaster was different to the Telecaster mainly in terms of comfort and structure. Its deep body and double cutaway design helped guitarists reach up the fingerboard and play higher notes. And its futuristic design appealed to America’s fixation with space and futurism. The chest and forearm contours and rounded edges gave it a level of comfort lost to the Telecaster. The three pickups, the tremolo system and the five-way switch gave it a greater level of versatility. Though first produced in 1954, it only began to climb towards the popularity it enjoys today in 1957 when Buddy Holly performed Peggy Sue with the Crickets on The Ed Sullivan Show, Strat in hand.

The Sounds the Instruments Make

Rock and roll music defined something of Western society in the ’50s in its search for grittiness. When you are able to find fidelity in the imperfect sounds of an overdriven electric guitar, you speak to a generation who seeks rawness over beauty. You strip back the frivolity by exaggerating the flaws of the sounds through volume; by screaming through broken amps to uncover the uneven, dirt of the thing.

Distortion of the sound was achieved through overdrive or ‘clipping’ (since the sound wave was ‘clipped’), which added to the growling, fuzzy sounds prominent in all corners of rock and roll music in the ’50s and beyond. The overdrive used in the rockabilly version of Train Kept A Rollin’ by Johnny Burnette, added something of anxiety in its growling, fast, dissonant composition.

Early artefacts of the now ubiquitous ‘fuzz’ effect were stumbled upon by artists using broken equipment; for example the damaged vacuum tube in the amplifier used in the recording of Rocket 88 by Ike Turner and the Kings of Rhythm. The rough guitar contrasts with the conversational lyrical tone, the wild tenor saxophone and jumpy blues piano. This grit made the RnB tune beloved by white youths, and as such, it is often called the first rock and roll song.

As a result, guitarists began to purposefully emulate the distorted sound. Grit was conjured by turning the amps up to a point that they were literally screaming, such as in Pat Hare’s I’m Gonna Murder My Baby. The voice screeches distressing lyrics through while the distorted guitar howls an ugly dissonance. The song has heavy metal undertones, said to have bred the general riff-construction of the heavy metal band.

Something’s in the Airwaves

Usually, the music reflects a disruption in the social moment because the people are ready to hear something different, even if they do not know it yet. There is some frequency already in the air to which the music is attuned. Audiences are willing to accept the sounds that, at first, they might wince or whine at. Young people force alternative music into the mainstream.

What is ‘cool’ is noble. The music that carries a message or the sound of a message taps into the ideological monotony of youth. In the ’50s, ‘feel good’ music became ‘feel great’ music. Music was no longer just about love but about sex; no longer just about life but about youth; no longer black or white but biracial.

White youths carried the ’50s rock and roll movement with the loose change in their pockets. The advent of the vinyl 45 record or the ‘single’ meant that young people could now choose and purchase the music they wanted to listen to at a cheap price. As many as three songs could be recorded on the record. Therefore, artists altered production to make approximately three-minute singles; a format which still persists today. The records were also more durable, gave a clearer sound and had better noise reduction.

The widespread popularity of rock and roll music pushed for accessibility in the marketplace. Both the pocket-sized transistor radio, such as the Regency TR-1 (1954) – a small, portable device – and the hi-fi Seeburg Select-O-Matic Jukebox (1953) – with one hundred selections – helped make music more communal and available to marginal groups. These items were successful both commercially and culturally, due to widespread disposable incomes and many young baby-boomers, who could listen to music away from their parents and in groups.

The Music Reflects the Children

Young people lacked prejudices in their musical choices. As young country and Western fans began to listen to black music, country musicians were invigorated to make RnB songs. Black audiences gratified black RnB artists who played jazz or hillbilly blues.

This era of music used the variety of sounds made by the electric guitar – the warm and spacious and growling and rough – to appeal to black and white audiences alike. The younger generation was making musical choices, different to their parents, by sharing specific physical spaces in which they could listen to new music. From the ’50s, many forms of music collided into a mainstream channel and musical taste was based on a feeling rather than a colour.