Omar Musa’s new collection of poetry, Killernova, is an innovative, form-blending exploration of identity, history, and healing.

Killernova (Penguin Random House) is an incredibly creative work. Blending visual and written art to create a unique, fresh artistic language, Omar Musa’s newest poetry collection is a nuanced exploration into the boundaries of language, history, fantasy, and a journey of self-healing.

An outstanding aspect of Killernova is the writer’s exploration into the mythologies that we hold with food, family, and love. His examinations are dazzling, particularly in interrogating the idiosyncrasies of these emotionally textured, oft-nostalgic bonds we create with those that we choose, and those that we must, love. With the pace of an experienced performance poet and a hip-hop artist, Musa’s words carry internal rhymes and rhythms that never stray offbeat.

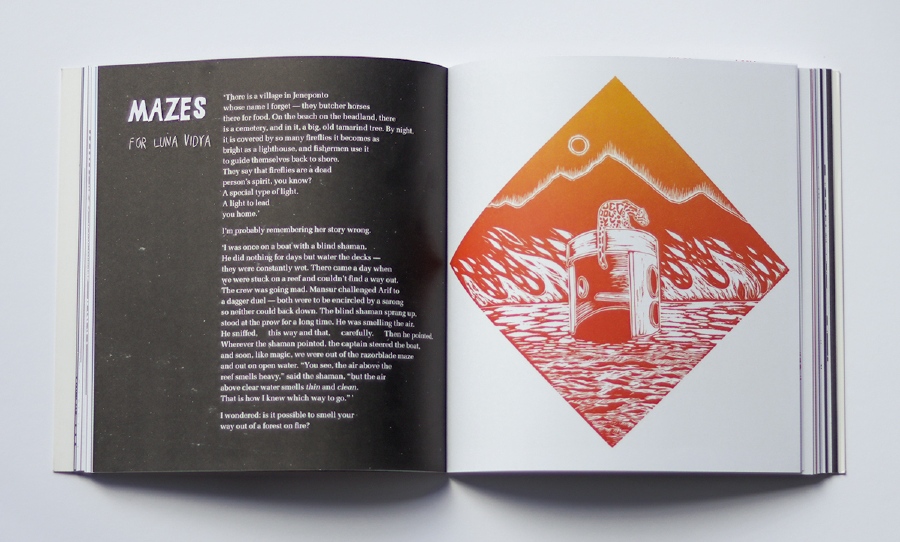

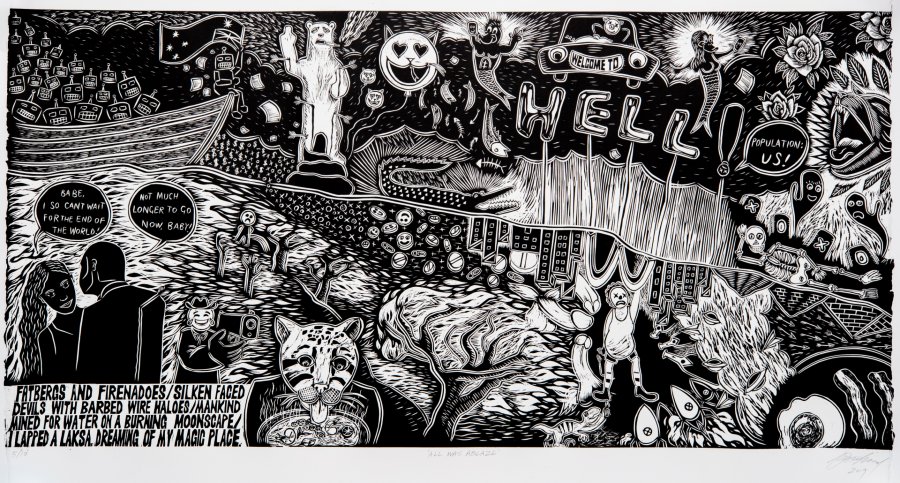

Accompanied by woodcut prints created by the writer himself, the poems of Killernova navigate the crossroads of two locations — Borneo and Australia — adeptly shifting through the consciousness of the narrator, as easily as they slip between their two worlds. Acutely self-aware, and constantly questioning his own beliefs, Omar Musa’s poetry collection is as impressive as the man himself.

A truly multifaceted artist (who else could include: playwright, novelist, musician, poet, and visual artist, on their resume?), we sat down with the writer to discuss his inspirations for writing Killernova, reconnecting with artistic purpose and his heritage, as well personal philosophies of writing.

HAPPY: Hey Omar! How are you?

OMAR: I’m good. Keen to share the new book with the world, and definitely a little nervous.

HAPPY: What are the nerves about?

OMAR: Oh it’s always nerve-wracking. Showing something new where you bare your soul, explore different ideas, and experiment with form. It’s always a big act of risk-taking. I think I wouldn’t be human if I wasn’t a little bit nervous about sharing that.

HAPPY: Fair enough! Well, if it alleviates your nerves at all, I really loved Killernova. It was such an enjoyable read. Being South Asian myself, and despite the differences in our cultural heritage, I feel like you really transcended those borders with the work. I had a really emotional reaction to it.

OMAR: Amazing. Thank you so much, did you manage to get your hands on a physical copy of it?

HAPPY: Yeah, I have it right here!

OMAR: Cool! Obviously, I made it to be an object that you could hold in your hands, put on your coffee table; that kind of thing.

HAPPY: Oh definitely, the illustrations were amazing. To be honest, I’ve never really read anything like it.

OMAR: That’s what I like to hear! And that’s what I was aiming for. There’s an element of risk in that, but I did come up with this visual language of my own. Obviously, one that’s influenced very heavily by South-East Asian woodcutters, like Pangrok Sulap, but I put my own spin on that type of protest poster. I tried to combine whimsical stories, scraps of history, conversations, personal experiences, and lines of poetry. And I was hoping that it’d be a brand-new form; something that’s really enjoyable, but that asks a lot of questions while encouraging the reader to do the same.

HAPPY: Out of curiosity, what was the catalyst for writing this book? Was there a particular event, revelation, or feeling that began the whole process?

OMAR: It’s hard to identify where an idea starts. I did become obsessed with the woodcut form about three years ago, after a really big event that I talk about at the beginning of the book, where I took a special trip to Borneo from the East Coast to the heart of the island. I took a public ferry, slept on the deck, travelled on foot, walked through the jungle, met the locals. It was a moment in my life where I was at a point of crisis. I had been having a lot of mental health problems, and I’d come to hate writing and performing which were supposed to be my lifelong passions.

Highly recommended if you’re looking for a gift for a poetry/art appreciator this Christmas. This book is a rare & glorious hybrid beast in Australian publishing. Killernova, by Omar Musa, (a substantial book of poetry, with accompanying woodcuts) is out at the end of this month. pic.twitter.com/RrZ3K0dK7E

— Vaxine Beneba Clarke (@slamup) November 12, 2021

HAPPY: Wow. That must’ve been rough.

OMAR: I think that we’re often fed this myth that you should turn your passion into your profession. But I do think that there are some pitfalls that come with that, and the passion can easily lose its sacredness. And that’s what happened to me. But on this trip, I came to realise I needed a new form to express myself, and it so happened that on this trip I came across the Tamparuli Living Arts Centre, where they were running a wood-cutting workshop.

I had been a huge fan of that style for years, but I hadn’t really managed to find a crew. So, I went over to Aerick LostControl, an activist who was running it, and just said: “Hey, can I learn? I’ll probably be really shit at this but I’m want to give it a go.” [laughs] He immediately agreed and invited me down, taught me how to use the tools, how to carve the wood, roll it with ink and then press it to the paper. After that, I was immediately addicted. I found this sort-of calling of, not just a new art form, but a way of connecting to my heritage. As I say in the book, I’ve got uncles that carve wood. I mean, all the different peoples of Borneo, whether they’re from the middle of the jungle or from the coastline, have all carved wood in such beautiful ways. So [Killernova] is like a modern remix of that.

HAPPY: That’s fascinating. When did this trip occur? I assume it before the pandemic?

OMAR: Yeah, it was in 2018. Coming back to your original question, I guess the main catalyst was being in lockdown. I had been banging my head against the wall for years, trying to write a novel, and feeling guilty for procrastinating and making woodcuts. But then I thought, why don’t I just follow that impulse? Why don’t I make a collection of these things that have brought me so much joy, and a sense of playfulness that I thought I had lost?

So yeah, I started putting [woodcuts] together with poems, thinking about that idea of escapism in lockdown where we can’t physically travel, but we can travel with our imaginations. And how important our imaginations become when we’re isolated. Killernova is also a celebration of community and collaboration, you can see it at the end of the book where it’s almost like the credits of a movie [laughs].

HAPPY: That’s exactly what I thought when I read the final pages!

OMAR: Yeah, I think there’s this myth of the solo artist who’s out there, creating genius work and being a lone figure. But that’s just not true. We’re the product of the communities that surround us, the people that have influenced us and supported us along the way. The book is a celebration that’s spread across two continents, two cultures, and two countries.

Omar Musa has always been a mainstay in Canberra’s art scene and a fast-rising literary star – drawn to the melancholy and the political, reflected in his work, writes @sally_pryor https://t.co/UUXEwlVujv

— Canberra Times (@canberratimes) November 19, 2021

HAPPY: In terms of the collaboration aspect, I feel that a lot of people view the writing of poetry as quite a solitary experience. But I noticed that there were quite a few “written in collaboration with” poems in your book, including Ghost Forest with Tishani Doshi. That’s gotta be exciting, she’s such an amazing talent. How did that collaboration come about?

OMAR: Oh, we’ve been friends for a long time. Probably since about 2010?

HAPPY: That’s fascinating, wow!

OMAR: Yeah, we met a long time ago. We were performing together at the Galle Literary Festival in Sri Lanka. It’s pretty funny actually, I’ve always loved her work and I think she’s an incredible writer and dancer. But I remember, I was giving her a bit of hell at that poetry reading we were doing, because she’s an incredible performer, but she was still holding onto the paper! And I could tell that she had performed that poem a million times, and I was like “You’re such a good performer, but let go of that paper! You’ll connect with the audience way more.” And after that, she did, and we ended up doing a book launch together in Seattle, and we’ve been all around the world with each other.

HAPPY: That’s amazing.

OMAR: But yeah, with Ghost Forest, I think Tishani was having a bit of writer’s block which I saw her post on Instagram. So I just sent her a Whatsapp and said: “Why don’t we just collaborate together on a poem?” I’ll send you an idea, you can hack into it, cut bits out, add whatever you want, send it back, and I’ll do the same. In my opinion, that back-and-forth exchange actually worked so well and turned out so beautifully. Another collaboration I did was with Inua Ellams, a Nigerian poet, in Fuck/Batman.

It was coming from this whole different philosophical perspective on making art, which was informed by my mentor Yee I-Lann who told me of the practice of sitting around a traditional woven mat and exchanging ideas and stories. Collaborating and cross-pollinating, rather than being a dictatorial artist who is imposing his will on his audience. But I mean, it’s obviously still my ideas and visuals, but they’re so informed by the people around me.

HAPPY: That’s such an interesting approach. In terms of the themes of Killernova, you do cover a lot of current anxieties surrounding the climate, ideas of the homeland, and racism. As a Brown woman myself, a line from the poem UnAustralia struck me:

“If you’re Black/brown/Muslim/woman/queer/smart/loud, and you dare question a cross-eyed sacred cow/they’ll twine newspaper headlines & lynch you/from a Daily telegraph Poll in UnAustralia…”

From my own experience, instances of racism can be horrifying to live through once, let alone relive to put down on the written page. How do you approach writing those experiences of trauma, whether direct or indirect, onto the page?

OMAR: With a poem like that, I was taking this principle that Bertolt Brecht once wrote of in To Posterity, where it may feel like writing poetry is waging a losing war. But without it, the people in power stride on unimpeded. So, it’s important to speak up and combat the dangerous narratives in the mainstream media. UnAustralia came out in a pretty personal way because I’ve been through all sorts of hateful attacks, like Mark Latham singling me out on Twitter, or my friend Yassmin Abel-Magied who was driven out of the country.

The poem really was about looking at these right-wing, “free speech” advocates and how hypocritical they truly are, when they seek to crush people like us, and our opinions, into the ground. And that’s exactly what that line is speaking to. Whenever someone goes against the status quo, against what they consider an “authentic Australian,” then all of a sudden, they don’t want your speech to be free!

But in terms of the way that I approach writing poems like UnAustralia, I tend to write them quickly and with a burning sense of purpose. Of course, I will then hone them, but they seem to come out in a really elemental way.

HAPPY: So would you say that those kinds of poems are more an expression of what you’re feeling in that moment? A type of documentation?

OMAR: Yeah, it’s a document of a feeling, but it’s also to make other people feel less alone, particularly anyone that has gone through those experiences. For the most part, I think it’s trying to hold up a mirror up to the world and sometimes, hopefully, that mirror can turn into a window. A window that shows the way the world is, as well as what it could be.

HAPPY: And I mean, regardless of how confronting it is to read, Killernova as a whole, does really provide that sense of comfort and relatability. It’s great work that you’re doing.

OMAR: Thank you! As you’re saying, it’s so confronting to go through these experiences but there’s something chemical about writing and art — where you can take these dark experiences or thoughts, and then through focusing on them in a certain way, transform them into something that is the opposite of how you felt in the beginning. Through the process of writing, the words become empowering, even though the original impetus was an act of disempowerment.

HAPPY: So it’s like reclaiming your power?

OMAR: I’d like to think so. But it’s hard because while I do take a lot of care with what I write, sometimes you can overthink and over sculpt something. So with poems like UnAustralia, which come out in a really raw way, I’ll often leave it fairly unedited.

HAPPY: That’s fascinating! As you were talking about earlier, it seems like the purpose and intention of art is something that preoccupied you when you wrote this book. I picked it up in your poem Poetry, where you’re interrogating that exact function of writing. Is the final conclusion of “writing a question?”, something that you’ve actively practiced throughout your entire writing career? Or was it something you came to when writing this book?

OMAR: I think it’s something I’ve been grappling with for a long time. The act of writing is one of interrogating yourself and the society around you. It’s not necessary to come up with answers; I don’t think that’s the writer’s role. Sometimes, bad writing can come out of trying to promote a self-righteous solution. For a flawed human who’s made so many mistakes —

HAPPY: As we all have!

OMAR: Exactly, as we all have, trying to act like I have all the answers would make me feel quite uncomfortable. So, I try to write from that nuanced, complicated place. And of course, there are also poems like UnAustralia that are more of a stance on a personal or political belief. But weirdly, UnAustralia isn’t representative of most of the poetic style in the book. That poem was more representative of how I wrote a few years ago and is, by far, the oldest poem I’ve written. That and The Flag were originally combined into one.

HAPPY: Oh, that’s so interesting.

OMAR: But yeah, Poetry was a fun one to write, and a bit of a mind-bender, too [laughs].

HAPPY: Definitely! Considering you’re an exceptionally gifted multi-hyphenate, being a visual artist, playwright, poet, novelist, musician — the epitome of an overachiever [laughs] — do you think that this ethos of “writing questions” applies to all art forms?

OMAR: Hopefully, not a jack of all trades and master of none [laughs]! But that’s a great question. I’d like to think that it’s applicable to all forms. A lot of what the book’s about and what I’ve been thinking about are layers. The layers that lie beneath the surface, whether it’s the Earth we walk upon or the surface of our skin; the layers of history and experience that lie beneath them. What I’ve always aimed for, is to convey complicated ideas in a simple and accessible way. In my mind, the best art does that, whether it’s painting, music, writing, or anything else.

Another way of saying it — which I’ve been banging on about recently because I’ve been super proud of coming up with it — is to have a user-friendly interface, but a complicated operating system, like an iPhone!

HAPPY: [laughs] Okay, an interesting analogy. Go on!

OMAR: With a book like this, I like to think that it’s inviting and extends a welcoming hand to the reader, rather than pushing them away. But then, once you’ve been welcomed into the world, suddenly there are these complicated, nuanced ideas.

HAPPY: That’s so creative, but it also makes a lot of sense. My last question, is that considering you’re a musician, have there been any records or artists that you’ve been listening to that influenced Killernova? At least a top three!

OMAR: That’s so funny, this is a good question. I feel like I do mention quite a few musicians throughout the book, but I’d have to say that Frank Ocean is number one.

HAPPY: I back it!

OMAR: Frank Ocean definitely comes up in the book at least once, so he’s definitely up there. This might be a bit of a weird one, but I’m going to say Harry Styles. I honestly didn’t really know anything about Harry Styles, but there’s a poem I wrote about it —

HAPPY: Yes! Harry Styles at Christmas.

OMAR: Yeah, Harry Styles at Christmas! It was just this really beautiful moment. And I was telling this younger person that I’d come across this artist called Harry Styles and had no idea who he was, and they were like “oh my God, you’re so old!” [laughs]

HAPPY: That’s hilarious.

OMAR: Who else have I been listening to? Oh yeah, Lianne La Havas! I listened to her a lot during the writing of this book. There you go!

HAPPY: Thank you so much for your time, and more importantly, for writing this book. It’s such a wonderful piece of art.

OMAR: I’m so grateful! Thank you so much for reading the book. As I said, it can be really nerve-wracking to deal with both big issues, as well as internal ones, with such vulnerability. And as you’ve said before, there’s a lot of darkness and heaviness to the book’s themes of mental health, colonization, family trauma, that kind of thing. But while a lot of my previous work was fuelled by fury and deep depression, Killernova is from a very different place — it’s much more joyful, playful, and grateful.

Killernova by Omar Musa is out on 30 November 2021 via Penguin Random House.