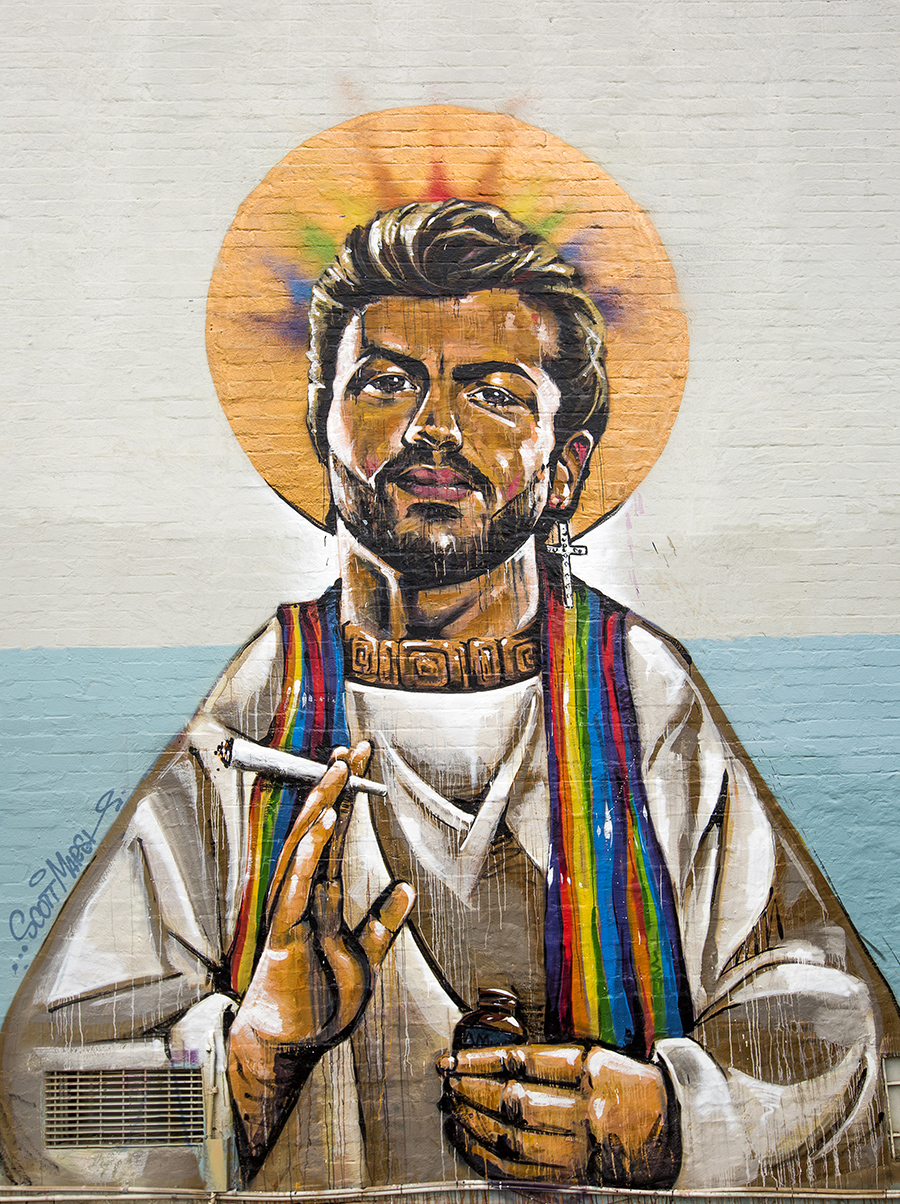

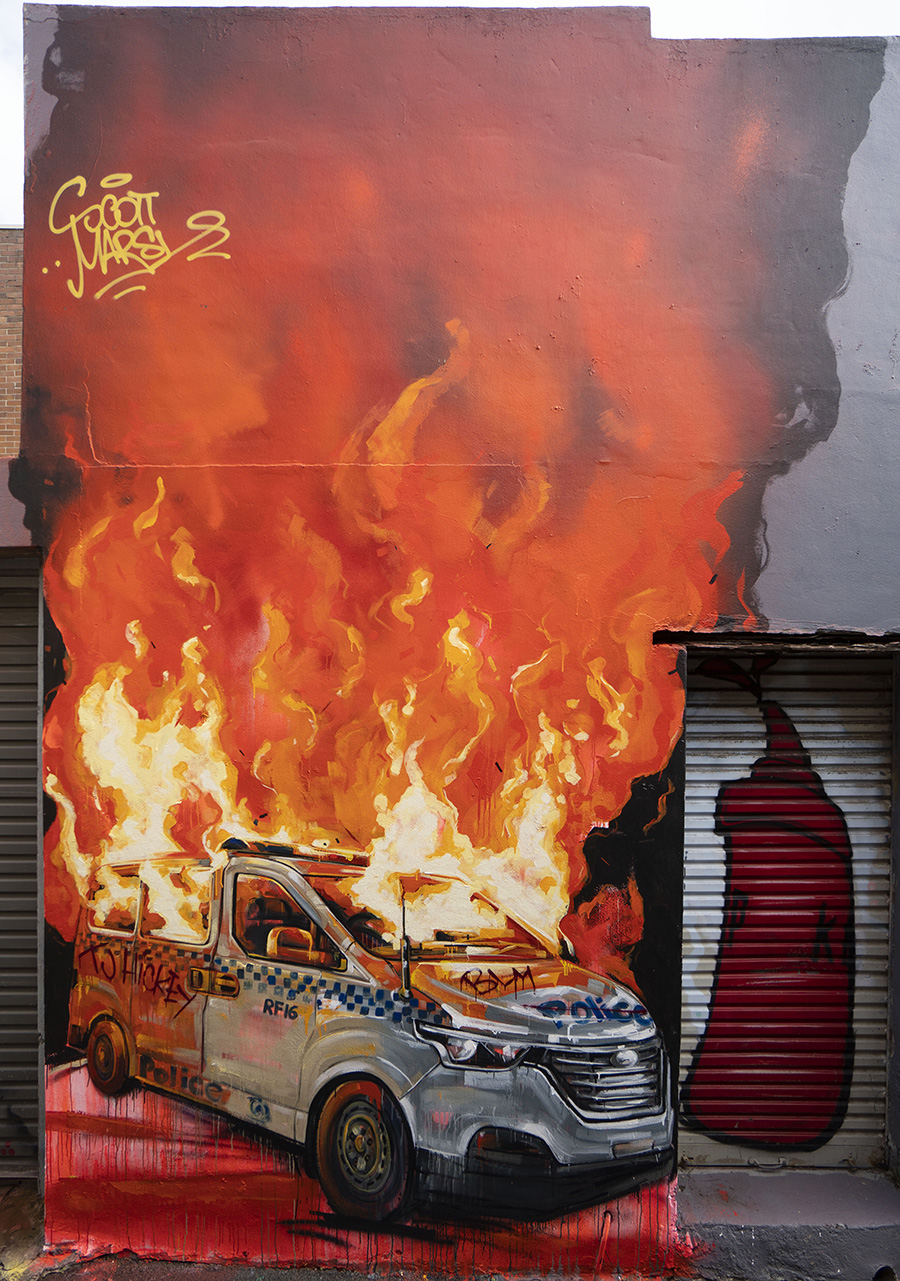

Few Australian artists have their work censored as much as Scott Marsh. Whether it’s police, politicians, or the pious, a great many people would love it if he just shut up. But he won’t.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 15. Get your copy here.

HAPPY: The first time Happy interviewed you was in 2017, and you said you “enjoyed being in the studio more than outside painting murals.” Is that still the case?

SCOTT: A little bit. Painting murals outside has its own unique set of challenges that I think studio artists don’t appreciate, or just don’t understand. Especially in summer in Australia on a 40 degree day, in direct sunlight, on a 14-foot ladder.

HAPPY: Physical challenges?

SCOTT: Yeah, it’s not the most fun. People want to come talk to you and ask you questions, just all the different kinds of things that happen when you’re outdoors. When you’re inside it’s nice to turn on a fan, sit in the shade, and listen to some nice music. You can really consider the work you’re creating, it’s a different process. With a mural, you’ve planned it and then you execute the plan because the scale’s so huge. In the studio you can sit and look at the painting for ages before making the next move, it’s a bit more improv.

HAPPY: What’s your studio space like these days?

SCOTT: It’s a shared space, there’s about half a dozen artists there, which I like. I could use a bigger space, to be honest, but to be on my own would be so fucking boring. It’s a living-in-a-sharehouse vibe, there’s friends to bounce ideas off, to throw stuff out there, and vice-versa.