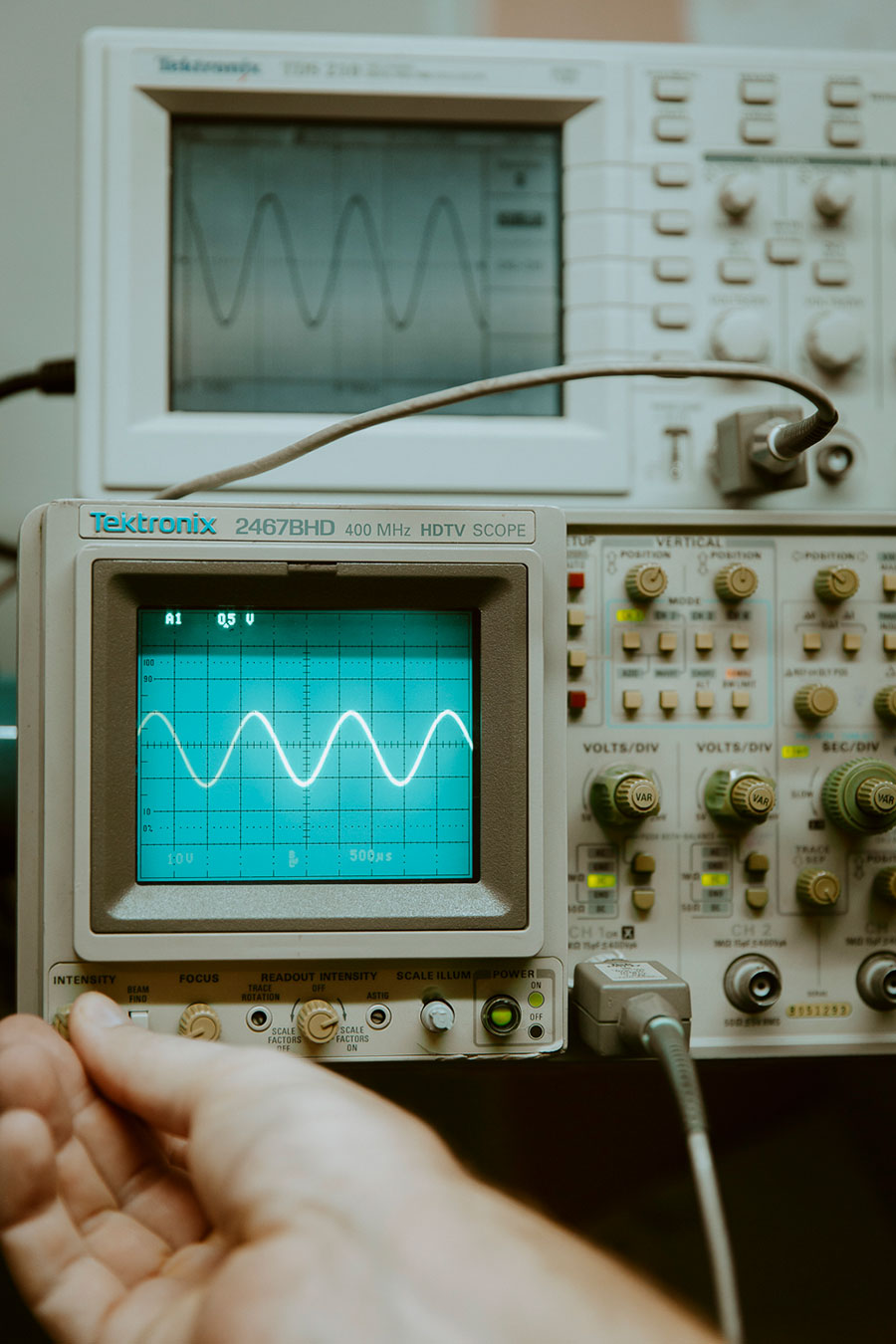

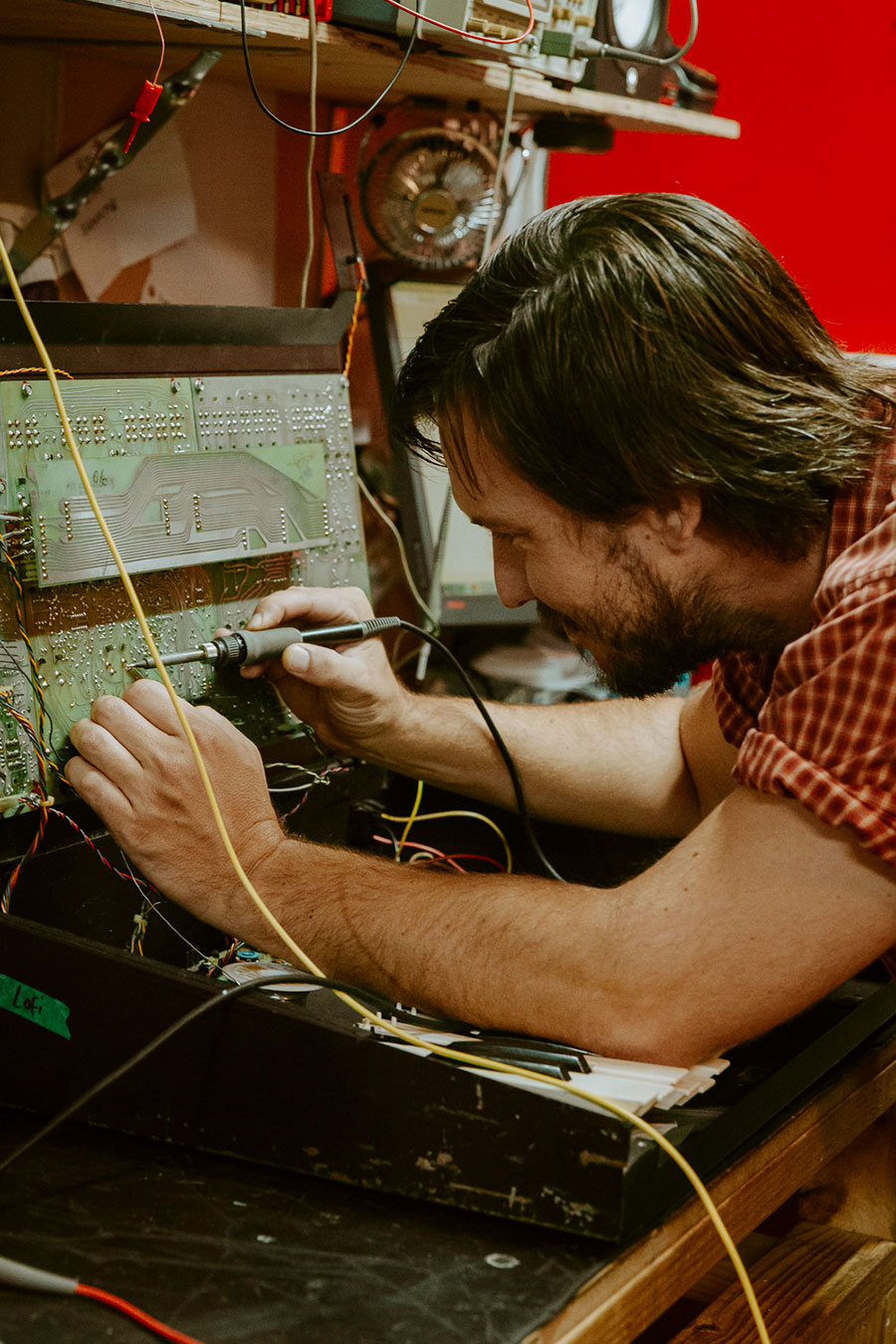

Every wondered what the back halls of a synth repair workshop looked like? Peek behind the curtain at LoFi Music.

Luke Aldred brandishes the soldering iron at Lofi Music, an instrument repair and refurb shop in Gosford. For years he’s been diving into the guts of rare synths, drum machines, record players, and other pieces of gear that some musicians would go their whole lives without seeing in the flesh.

People come to Luke with their broken synths. Most of the time he sells them back into the world, but the really one-of-a-kind gear? That’s another story.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 14. Order your copy here.

HAPPY: How does one get into instrument refurbishment? Were you a musician first or an electrician first?

LUKE: I was a musician first I reckon, then there were the technical skills and knowledge. I studied electronics and also studied music and production, so I did a lot of work as a sound engineer prior to going into the tech side.

HAPPY: So you really have to have both.

LUKE: I think so. Some of like the real technical people I know who are engineers first, they may not have a musical understanding of the equipment either, or the ear. I think the ear is pretty important to it as well. But obviously, everybody comes from different backgrounds.

HAPPY: That’s what I was going to ask. How much of this is purely tech and how much of it is having that engineer’s ear?

LUKE: I think it’s probably equal parts of both.

HAPPY: For instance if you’re repairing a [Roland] Juno, could someone who was a classic electrician type repair that properly? Or do you need to be someone who knows how it’s meant to sound on the way out?

LUKE: Yeah, exactly. Having an understanding of it as a musical instrument is definitely advantageous, but I think an electrical engineer could probably fix a Juno.

HAPPY: But would you trust them to?

LUKE: I think they wouldn’t appreciate the sweetness of the sound, hey? One of my really good friends and a bit of a mentor is a rigid engineer type. And he has no ear, he even admits that he has like… cloth ears. So he can’t hear anything different, he can only understand the spec of it, or the technical nature of it.

“People will amass huge amounts of really good gear and then they get to a point where they’re like, ‘okay, I’ve got way too much epic gear.'”

HAPPY: Personally, I probably want someone who had that love for the instrument as well. It sounds like you get some sort of enjoyment out of repairing.

LUKE: I reckon. There’s a definite fulfilment in it, bringing it back to life. There’s a kind of green element to it now as well, I would say. Recycling.

HAPPY: Of course, I hadn’t thought about that.

LUKE: Because we’re rescuing a lot of junk. We’re taking stuff out of landfill.

HAPPY: How many great old synths can you find in landfill?

LUKE: Oh heaps. I was thinking about that with this Korg we have now, it’s like a late ’70s Korg monosynth and it sounds insane! It exploded yesterday but I rebuilt the power supply. I was thinking there must be a few of them in landfill ’cause they’re heaps rare and I can imagine people throwing them out.

HAPPY: Something as simple as the look…

LUKE: Yeah! But now you look at that thing now and it’s amazing.

HAPPY: Where do you source this broken gear?

LUKE: We’re sourcing things, I don’t know – I guess we exploit any possible avenue to get them.

HAPPY: So sometimes literally landfill?

LUKE: Yeah, I mean you can’t find that great stuff in the trash. But we buy from anywhere, we buy or we get given, or we also import internationally from various countries. We’ve had some big loads land, like half-full containers.

HAPPY: Is it a regular occurrence when you have someone giving up on the music life? A moment of, ‘here’s all the stuff I need to get out of the garage?’

LUKE: Yep, for sure, for sure. And I think overseas there’s a lot of that as well, like ageing population and stuff like that. People will amass huge amounts of really good gear and then they get to a point where they’re like, ‘okay, I’ve got way too much epic gear.’ So we get that a lot, someone wants to clear a few rooms and they might contact us saying ‘find a good home for them.’

HAPPY: Right.

LUKE: They want them to go somewhere good, as well.

HAPPY: That’s fair, that comes back to the romance. On the other side though, beating up instruments is a classic piece of rock and roll showmanship. Are there any people who come through here regularly, generally treating their instruments bad but want to keep them working?

LUKE: Not really. We don’t really do too many returns, I think this kind of gear – because we’re not repairing guitars and amps so much, or drums or something like that – these things I think people tend to put in my studios and cherish them, or carry them in cases if they’re touring. But we obviously see a lot of the same things like Junos, for example, because they’re popular and because they have certain issues they fail over time. Issues which we can refurbish.

HAPPY: On the point of knowing the instruments, are there some golden rules that apply to say, synths or drum machines, or do you need to learn a whole new set of rules to every time something new comes through the door?

LUKE: There’s definitely some common ground, but a lot of the time the circuits can be very different, as well as the electronics involved. Obviously things like power supplies are always gonna have a lot of similarities. So the common points would be things like that; power supplies, input, and output.

HAPPY: Do you ever have to contend with makers protecting the secrecy of their circuits? I think it’s more of a thing with guitar pedals.

LUKE: You get that a lot, and it makes it hard to repair mostly modern gear. A lot of the oldest stuff is available, because you know, people have shared it for so many years. And maybe those companies don’t exist anymore, so it’s free information or out of copyright. But the modern stuff, that’s where it becomes difficult because the companies, they keep it all in house. It’s like, if you buy a Mercedes, you know, you’ll have to get that serviced by Mercedes. They won’t accept it being serviced anywhere else. It’s a bit of a corporate structure, I guess. So yes, mostly with new gear.

“Most things you can repair if you screw up, but if you do a big scratch on the front panel of a Jupiter 8 or something, you’re in trouble.”

HAPPY: Are there any really common problems?

LUKE: One of the main ones that we always repair is the Juno-106, that’s probably a good example. They have this failing voice chip issue that’s heaps common. And you can read all about it online, there’s a million posts about it. So anyone who’s buying a Juno or owns one, they’ll probably know about it.

HAPPY: Is buying and Juno just a ticking time bomb, then?

LUKE: Kind of, but there’s certain things you can do to rectify the problem. It’s just a really common problem that’s inevitably going to happen to all of them. But now there’s all kinds of ways you can get around it. And some really good reproduction parts that you drop in there as well.

HAPPY: That’s something you can make yourself?

LUKE: No, you can’t really make it yourself. You can refurbish the old ones yourself using a pretty tricky process, but you can do it, otherwise we buy them from this guy. He’s a well known manufacturer.

HAPPY: Man, so it’s that large a problem?

LUKE: Exactly, because the Juno was such a mass produced synth and it’s still so popular. This guy has remade that part. A few people have tried but his one’s the best. And we buy them in bulk. The company’s called Analogue Renaissance, he’s Belgian. He makes some good stuff. Anyone who knows about Junos kind of knows him. And those ones they’ll future proof so you’ll never have that problem again.

HAPPY: You’ve got a [Roland TR-808] downstairs, you’ve got some stuff that I’ve just never seen in real life. Is there some degree of fear that comes with refurbishing something like that? Even if it’s just the expense?

LUKE: I know what you mean, definitely. I think I’m just well and truly over that now. If it got to something super high value, then I would be a bit worried about making a mistake. Most things you can repair if you screw up, but if you do a big scratch the front panel of a [Roland] Jupiter 8 or something, you’re in trouble. Though I think I got over that fear long ago, to answer the question, by stating small. I started with, you know, Junos, and I built my way up.

HAPPY: Any really large problems that you’ve had? Where something was written off?

LUKE: Nothing that we’ve caused, I’d say.

HAPPY: How about the other way around? Someone doing some horrible damage to something that they bring to you and just say “please fix.”

LUKE: I just had a phone call from someone saying like… this is a studio owner, he’s said he got this beautiful thing called an ARP Quadra, a heaps rare and vintage ARP, a massive thing – they’re huge. They’re in the $20K range to buy, but he lent it to a famous touring band, someone everyone would know, and that was four years ago and then it came back recently just completely trashed. He’s like ‘I really don’t know what to do with it.’ So I’m going to have a look at it on Monday. It’s pretty funny.

HAPPY: Don’t give your stuff to touring bands.

LUKE: I reckon that’s a good rule.

HAPPY: And don’t take your expensive shit on tour?

LUKE: Just sample it.

HAPPY: Do you make your own sample packs?

LUKE: Predominantly [my band makes] music with samples, but we don’t sell the sample packs we make for ourselves.

HAPPY: It seems like with the amount of gear that comes through here, you’d be in a position to.

LUKE: Sell sample packs? It’s true. It’s a time factor though, it’s time consuming, but we’ve made a few cool ones. My mate made one from his out-of-tune piano, some honky tonk piano, he multisampled the whole piano, it was pretty cool.

“They’re in the $20K range to buy, but he lent it to a famous touring band, someone everyone would know, and that was four years ago and then it came back recently just completely trashed”

HAPPY: How tempted are you to ever create your own product? Similar to the sampling thing, I imagine you have a good knowledge base, and you’d also understand what musicians want from their gear.

LUKE: I guess we think about things like that, going into production of something. We’ve actually produced spare parts, we’ve manufactured replacements for things. So we’ve already sort of started on that, we do actually retail a lot of spare parts as well through our shop, so that’s good stuff. But as far as building some gear… we’ve got a few more things in the works.

[Luke points to a modular-looking synth behind me]

LUKE: I built that synthesiser, though.

HAPPY: Looks like a beast.

LUKE: It’s a big modular thing. I built that in high school, when I was like 17, so it’s pretty old.

HAPPY: Do you use it much?

LUKE: Not much anymore, but that’s hilarious because I actually made a sample pack of that machine, my mates are using it now.

HAPPY: We’ve come full circle.

LUKE: I guess at the moment we’re trying to fill holes in the market for refurbishment, because there’s a good potential for return there.

HAPPY: Financially I can imagine that building a spare part for a synth that 10,000 people own is always gonna be first on your list of priorities.

LUKE: It is, because we can use them ourselves and then there’s the retail side. There’s a guy up here on the coast who actually just built his own Space Echo. And it’s beautiful, he just manufactures out of his garage on the Central Coast, which is pretty sweet.

HAPPY: There’s a massive amount of hobbyists around at the moment.

LUKE: Yeah, the modular synth stuff is the other thing right now.

HAPPY: Oh yeah, that’s huge at the moment. Does much of that come through here?

LUKE: No, not at all.

HAPPY: Why do you think that is?

LUKE: It is very trendy… I mean, there seems to be a fairly solid amount of people doing it.

HAPPY: Is it something that’s hard to break?

LUKE: I think it would actually be hard to fix? Maybe the people try to fix it themselves – and there’s also the price point, if a module costs you $200, it’s probably not gonna be economical for us to even bother to repair it, you know what I mean? But maybe the manufacturer might be able to. Usually a lot of those people are into the DIY side of it as well, so maybe they have a crack at it themselves.

HAPPY: So you still play as well, what’s your personal setup? Or do you find yourself jumping on anything and everything that comes through the shop?

LUKE: I mean, we do have a pretty crazy, complex setup when we get stuck in there, because of what we have access to. We have a big console, a big rack, it’s pretty serious.

HAPPY: I would find it extremely tempting to not let some of this gear go.

LUKE: Oh this is the stuff we’re keeping, for sure. Our setup is pretty much Minimoog, [Oberheim] OB-8, we have several Akai MPCs that we use to sequence everything. We use them, the [Roland TR-808] has recently gained a very high priority in the setup. And then a variety of crazy analogue synths, whatever’s coming through I guess.

“That system would have been worth like four, five hundred thousand dollars, or something. You know, more than a couple of houses.”

HAPPY: Do you try everything that you repair?

LUKE: Yeah, pretty much.

HAPPY: What’s the moment then? The moment you go ‘oh, I have to keep this.’

LUKE: It’s those certain things that grab you, that sound great, feel great, inspire you as well. I guess at the end of the day I like having fun with them as well. Usually the bigger end stuff is the keepers.

HAPPY: Do you ever have to weigh up the potential cash something rare or expensive could bring in, versus how much you want to keep it?

LUKE: Pretty much every time, to be honest.

HAPPY: But you gravitate towards keeping it?

LUKE: Yeah, it’s a hard decision, but I do have my partner Jess to assist in the decision. The other thing with them is they’re really appreciating assets. They don’t devalue, the way that the market is going at the moment.

HAPPY: We’ve talked about a few already, but is there anything that’s come through over the years that’s extra rare?

LUKE: Probably the ones we keep, like that miniMoog, that [OB-8]. The [Roland] Jupiter-4 I had a couple then I was like, ‘I’m not selling the next one.’ And so I finally got another one and kept that – that’s really sweet. As far as the super rare stuff, I mean, that Synclavier system downstairs…

HAPPY: Yeah, I was looking at that. I’d never heard of one of those.

LUKE: They’re a bit like a Fairlight [CMI], a huge, kind of revolutionary digital workstation in the ’80s. That system would have been worth like four, five hundred thousand dollars, or something like that. You know, more than a couple of houses.

HAPPY: Well, looks like it was in a few pieces still.

LUKE: We’re slowly rebuilding it. It’s pretty good though, it’s coming along. So that thing – as far as the rareness, I’d say that would be up there.

HAPPY: It must be very satisfying when something like that turns back on.

Find out more about Lofi Music on their website.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 14. Order your copy here.