An accidental sequel brought about by ravaged eardrums, Harvest Moon pinned Neil Young’s thrasher acclaim against his muffled folk heritage.

25 years ago, a resurgent Neil Young released Harvest Moon. Today, the sort-of-sequel to Harvest (1972) is a bookmark wedged in the centre of one of the most interesting and fraught periods in the singer/songwriter’s monumental career.

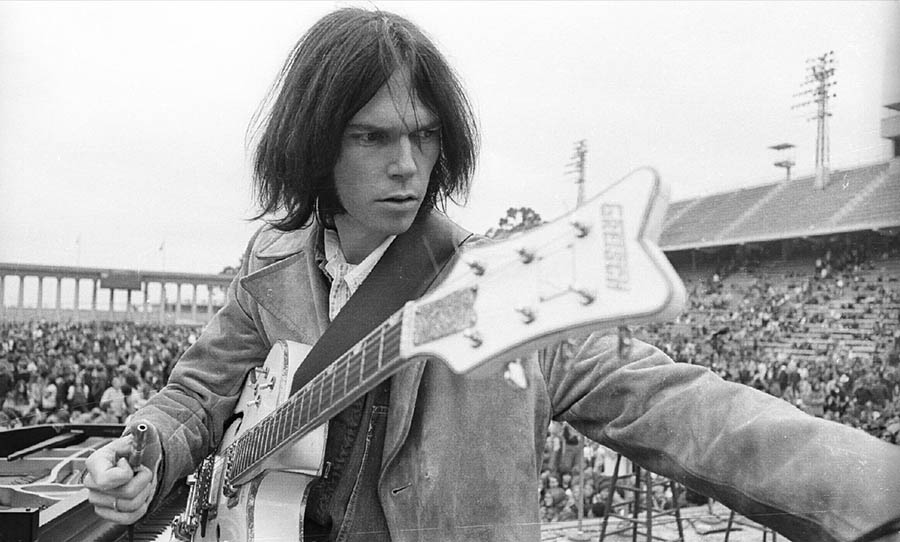

In the early ’90s, when grunge was a relentless ooze across youth culture, Neil Young was cool again. After reuniting with Crazy Horse for the rip-roaring and brilliant Ragged Glory (1990), the chugging guitar rock of Young’s soft country roots was resonating with young music fans.

He was heralded the ‘Godfather of Grunge’ after ’90s icons Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder cited him as a huge influence on their songwriting. He even took unorthodox art punk heavyweights Sonic Youth on tour with him.

While Young’s popularity grew among adolescent music fans, his return to form was winning back an older, disillusioned fan base after a dismal period during the ’80s, which consisted of several unsuccessful experiments with new genres, including a puzzling rockabilly album, and a subsequent lawsuit from his record company for making music that was “unrepresentative to Neil Young”.

Throughout his career, and even up until 2016, the rate in which Young has released albums has proceeded inexorably (38 and counting). However, after touring Ragged Glory he developed hyperacusis, a condition that makes it sounds like everything is turned up way too high, which eventually led to tinnitus.

The result of nightly onslaughts of thumping drums and squealing feedback while touring with Crazy Horse and Sonic Youth in tow forced Young to retreat to his sacred California ranch to rest his ears and wait until things got back to normal.

When they did, another thrashing effort from the Godfather of Grunge was impossible and the decision to make an abrupt return to his country origins on Harvest Moon, while surprising to his new fan base who were awaiting a follow up to White Line and F*!#in Up, was inevitable.

“I made Harvest Moon because I didn’t want to hear any loud sounds,” Young stated in a 1995 interview with Mojo Magazine.

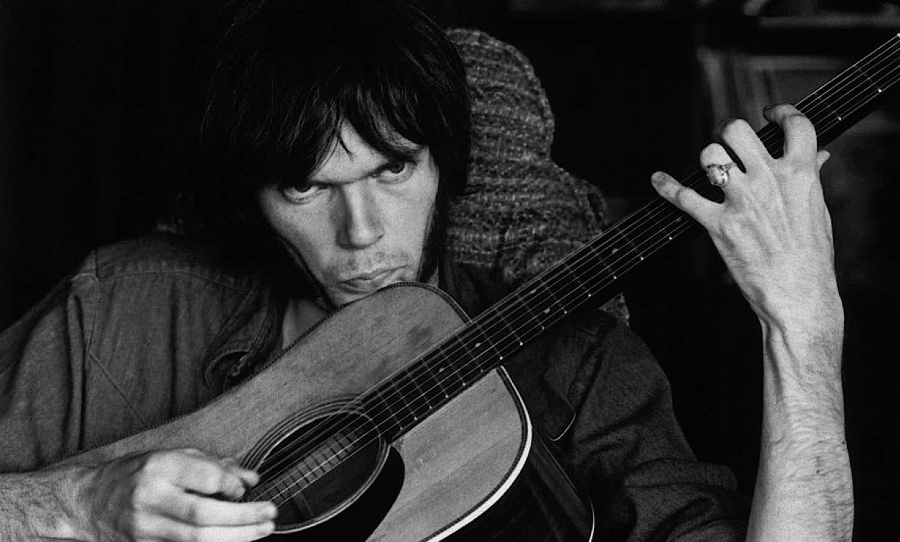

Because Young’s hearing had become softer, he was forced to pack away all the chaos, clutter, hype, and scrutiny that had been following him for 20 years to make space for an album where he was able to recline back into a much gentler and tender sound, and it turned out to be the making of Harvest Moon. It’s a record bathing in nostalgia, and there isn’t a genre out there that can conjure sentiment and wistfulness as well as country and folk.

The album is as stripped back as Young could make it without regressing to just himself and an acoustic guitar. His pinched vocals are backed by drums, bass, and piano, and enriched when the notes slide off co-producer Ben Keith’s pedal steel guitar, but when the songs steer towards a crescendo, Linda Ronstadt and James Taylor’s sublime harmonies are all that are needed to propel them.

Album opener Unknown Legend, with its imagery of a nomadic wanderer working in a diner, and Old King, a sardonic and cheerful ode to his deceased dog, are bright cuts from a tracklist that dances in light and darkness.

At the time of recording, Young was in his mid-forties, both a father and a husband, and was reflecting on a career where he had grappled with success, controversy, and tragedy. His confrontations with these themes are woven into songs like the title track, written only for his wife Pegi Young (divorced 2014) with lines like: “When we were strangers I watched you from afar, when we were lovers I loved you with all my heart.”

When Young hit the road to tour Harvest Moon, there was a dilemma. In the audience were two sets of fans: the middle-agers in suits waiting to be soothed by Heart of Gold and the ballads in his back catalogue vs. the beered up teenagers in shredded flannel shirts who had become acquainted with Young’s heavier stuff via a cover album released in 1989 that featured Dinosaur Jr and The Pixies.

Neither were able to co-exist and Young would frequently stop songs halfway through because he was distracted by the shouts and jeers of the younger audience.

As a result, he went back into the studio for album number 13, which saw him collaborate once again with Crazy Horse, much to the horror of his ear drums, for the sombre Sleeps with Angels.

Now, why is Harvest Moon a sort-of-sequel to Harvest and not, well, an actual sequel? The 1972 classic, released 20 years prior, remains Young’s most critically successful album (any record that features Heart of Gold and Old Man is bound to be).

The similarity in style, the semi-identical title, and the fact that both albums share many of the same players inevitably invited suspicion of the fact. That being said, Young is having none of it. Here’s what he told a Canadian radio station just after the album’s release:

“The whole idea of following up the Harvest album is something that’s contrived more from the standpoint of record companies… the thrust of the albums is different, even though the subject matter is similar.”

Perhaps Young regrets creating such a plausible link between the two albums, whether it was deliberate or not. Either way, Harvest Moon, an album more than worthy of a retrospective review a quarter of a century after its release, never needed to ride on the coattails of its older sibling.