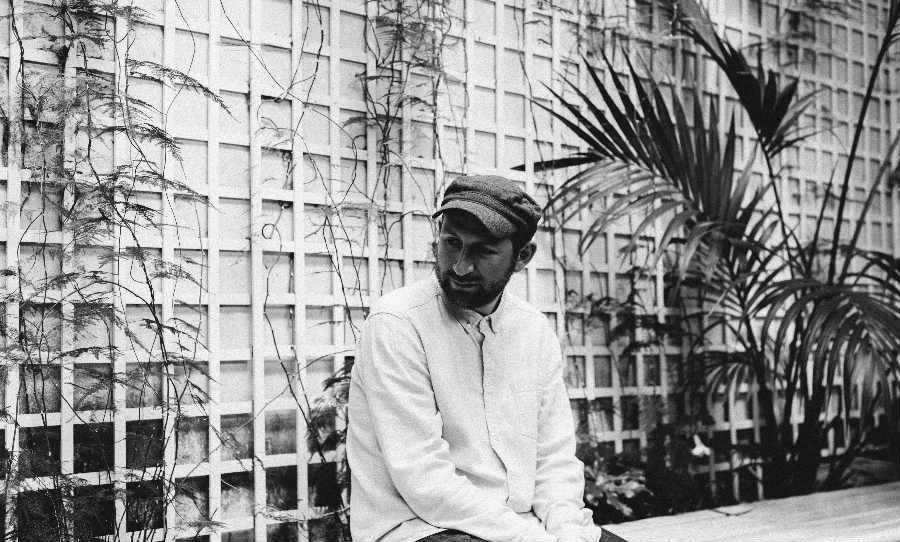

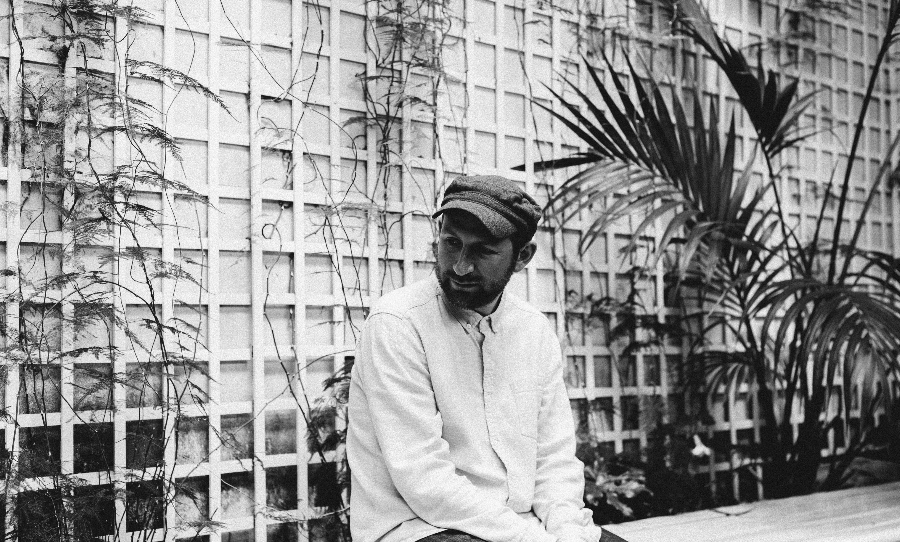

Prominent London trumpeter Matthew Halsall is certainly at the top of his game both mentally and musically. Having studied transcendental mediation alongside GTSE exams he has both founded one of London’s most progressive jazz labels, Gondwana Records, as well as surmounted some powerful philosophies on life.

His effortless yet deliberate playing has garnered him comparisons to the greats and a tide of tongues spreading his name. We recently caught up with Matthew Halsall to chat about his new album Oneness and the transcendental components of spiritual jazz.

Matthew Halsall exacts profound insight on the freedom of jazz, the death of the ego and importance as a musician of listening to the listener.

HAPPY: So your new album Oneness is soon to hit the world. How does it feel releasing an album recorded over 10 years ago?

MATTHEW: It feels good! It’s something I’ve been enjoying for a long time behind the scenes. I record a lot of music that I don’t release so this doesn’t feel that different to my daily life. But it felt like a really good time to release this record as it’s a ten year period and it’s done full circle for me. The Oneness record is very much about finding the right musicians so there’s a lot of different ideas there with a Sitar player and some harpists and Indian drone boxes. I’m at the point were I’m currently rebuilding a band again it felt like a really nice refreshing point to reflect on the beginning of how things started.

HAPPY: You have described Oneness as spiritual meditative jazz. Is jazz spiritual for you?

MATTHEW: Yeah I guess it is. Well I mean most things in my life are spiritual. I studied transcendental meditation and I still do Buddhist meditation and I think that has an impact on the music that I make. If I were making electronic music I would probably call it spiritual electronic music. I know that in the jazz world the term spiritual has become a bit of an on trend thing but for me it’s very genuine and aligns with the way I live my life.

HAPPY: Three tracks on the record feature the late Stan Ambrose on the harp. Tell me a bit about your relationship with Stan and how these recordings came about.

MATTHEW: I used to live in Liverpool. It’s a city very close to my heart because my grandmother was from Liverpool. When I moved there I kept going to many different cafés but one, in particular, is the Green Fish Café because it’s this nice vegetarian, kind of hippie hangout. And there this old guy playing harp and we would play for his lunch basically. They gave him free food and he gave everyone beautiful harp solo performances. He was just a really lovely, sweet old guy that played very free and a very beautiful meditative style. I got chatting to him on a number of occasions and we became very close friends. We did various performances together in Liverpool where I’d play trumpet and he’d play harp but he didn’t drive and he was very old so it was kind of tricky to get him to around. But I decided, and I’m really happy that I did, to pick him up in Liverpool and we drove to Manchester and did this recording. That was one of the very first recording sessions I did with harp and it was very special. Stan played the whole session and it was really beautiful and I think the reason that I wanted to release this is because over the course of ten years I’ve kept going back to this music and have found quite a lot of depth and beauty in it. Stan was a really well respected legend in Liverpool. He used to have a radio show on BBC Liverpool where he used to be a presenter. He was just a really lovely guy and I’m happy to have such a good soul on this record. (Stan Ambrose passed away in 2016.)

HAPPY: Is that something that is important to you, seeking out musicians naturally on your journey as oppose to professionally?

MATTHEW: I think so yeah. I like to find musicians that wouldn’t all be in the same clique. Pretty much all of the bands that I’ve put together haven’t been conventional or an easy process it’s a number of people from different parts of the North of England who are quite unique. I have to have a connection with them in terms of personality and respect, both musically and in terms of their character and philosophies on life, Stan being a great example. That’s definitely true of all the musicians that I’ve worked with.

HAPPY: You have talked about searching out musicians that play without ego and that a lot of young musos wanna show their flex after leaving study and school. How important is it to play music and perform without ego?

MATTHEW: Well I think it’s really important in jazz because jazz is one of the freest forms of music. There’s definitely a thing with the educational side where you’re taught how to do very complex stuff that once you achieve that you feel very confident and you want to show it off. But the music that I try and make is very much a collective sound and a collective respect for each musician. Everyone gets a solo on the gigs. I do a very balanced set list and tell everyone where the solos are so that it’s equal. It’s just so that nobody is overplaying during solos or underplaying, it’s about finding that really nice marriage of musicians really listening to each other and working as a group. It’s a bit like football. Not for the pack mentality of it but for the managerial side. It’s about getting 11 talented athletes together and making them perform in harmony so that everybody looks good and sounds good in a musical sense. So yeah it’s something that I’m really conscious of. I can’t count how many jazz gigs I’ve been to where musicians are just over playing and self indulged. They are just in their own realm on the stage and they have forgotten about the listener. The listener is very important to me because I’m as much a listener as a performer.

HAPPY: Is there one simple philosophical rule that you could give to help people achieve ego death?

MATTHEW: Sometimes it’s just a natural thing. The musicians I tend to work with are quite mellow respectful people. I guess it’s just that thing of remembering the audience. Even when you’re making a record remember that people have to sit down and listen to it. As much as a 50-minute solo can be amazing it can also be quite an awkward experience to listen to. But it’s tough because you have to balance that with freedom. The balance of being completely creatively free but also being conscious when performing that people are listening. The whole point of music for me is perhaps different to some people. For some it’s a personal journey and a challenge individually whereas for myself it’s a collective journey about trying to unite people.

HAPPY: It’s interesting you talking about simplicity because my favourite song of yours is The Move and it gives me chills every time I hear it. That solo isn’t technically the fastest in the world but it’s just oozing with power and emotion.

MATTHEW: Yeah thanks! That was an intense session. I remember recording that and it was quite a difficult time in my life where my parents were in the middle of divorcing and it was this whole transitional period in my life and everything was quite unbalanced. But there’s intensity and an emotion captured in that tune that people talk about a lot, which is really interesting. For me all the songs on that record say a different thing but The Move seems to connect with a lot of people it’s a really interesting song.

Check out Oneness below:

HAPPY: Where did the inspiration come to record a Jazz album founded on essentially non-jazz instruments such as Harp and Sitar.

MATTHEW: Well, being a DJ I’ve been obsessing over production and music in general. One night when I was 15 the Manchester DJ Mr. Scruff was playing You’ve Gotta Have Freedom. My friend’s parents used to sneak us in to watch Mr. Scruff Dj, which was amazing. Then that introduced me to Pharaoh Sanders then I basically searched for everything Pharaoh Sanders had played on and discovered Alice Coltrane and that was the first time I heard a harp in a Jazz context as well as a tanpurah drone box. So the Alice Coltrane record Journey In Satchidananda and The Cinematic Orchestra’s Everyday are two of the albums that gave me a really strong direction in terms of the sound and to an extent the production of the future records I’m going to make. There was a really important point in my life and I was doing transcendental meditation at a Maharishi School whilst doing my GTSE studies for the last two years, and the combination of discovering Alice Coltrane and transcendental meditation and discovering the Cinematic Orchestras new approach to the production of loop and jazz. That’s how it all came about.

HAPPY: There seems to be vibrancy in London right now with a significant resurgence in Jazz, especially in young people. Why do you think that is?

MATTHEW: I think it’s been bubbling up for quite a long time. Moses Boyd and others have been around for quite a long time now. But I guess the media has only just put a spotlight on those musicians. I first met Moses Boyd when he was drumming with Zara Macfarlane when he was like 17 and I guess music goes through cycles and different genres appeal to certain musicians at certain points in their life and at the moment the combination of Afro beat music and Jazz is really connecting with a younger audience. Also a lot of it’s down to people like Charles Peterson and Mr. Scruff and DJ’s that have a mass audience and are constantly educating and pushing musicians to listen to more jazz and African and soul and hip-hop. The interesting think in the UK with jazz at the moment, and it’s quite similar in Australia actually, is that musicians aren’t just going I’m a jazz musician so I’m going to make a pure jazz record. They are influences by so many genres around the world and they put that all together to make these really interesting records. In London they have pinned it all down to being UK jazz but it’s not there’s a lot of crossover and its happening everywhere. That’s why it’s blowing up. It’s not just jazz. Jazz composers in the UK and further afield are becoming more like DJ’s and opening up lots of cross-genre pollination.

HAPPY: Do you think that is perhaps because of the innate freedom of Jazz form that it’s open to so many interpretations?

MATTHEW: Yeah I think jazz has always been a place where you can bring in a harp or with the Portico Quartet you can bring in a hang drum and use effects on the saxophone. There are no rules as to how you make a jazz record. But if you just say you’re a neo-soul artist it’s quite a specific sound and production technique. There’s definitely playfulness within the world of jazz where you can say ‘I’m a jazz artist but I’m influenced by hip-hop’. So it definitely allows a lot of freedom where other genres sometimes stifle peoples growth.

HAPPY: I could talk all day but I’d better try and wrap it up. What’s next for you Matthew?

MATTHEW: Yep so Oneness is coming out on the 27th Sep. I’ve got two re-issues with my very first two albums Sending My Love and Colour Yes they never actually got pressed to vinyl and they were the very first releases on Gondwana Records and we had no money when we started so they never got mixed or mastered properly. So we’ve remixed and mastered them, redone the artwork and added some bonus tracks and they’re coming out in November. I’m also in the middle of recording my new album. I’ve got I think 40 tracks that I’m slowly recording and seven down that I’m happy with. The new band is in a really good place, we meet up every Wednesday and record and rehearse set lists.

We have a residency in Manchester that on the last Thursday of every month where we are pushing and testing all the new material. We have a really good set up now to push the music really hard for the next couple of years and get a lot of records out. Back to full creative capacity now!