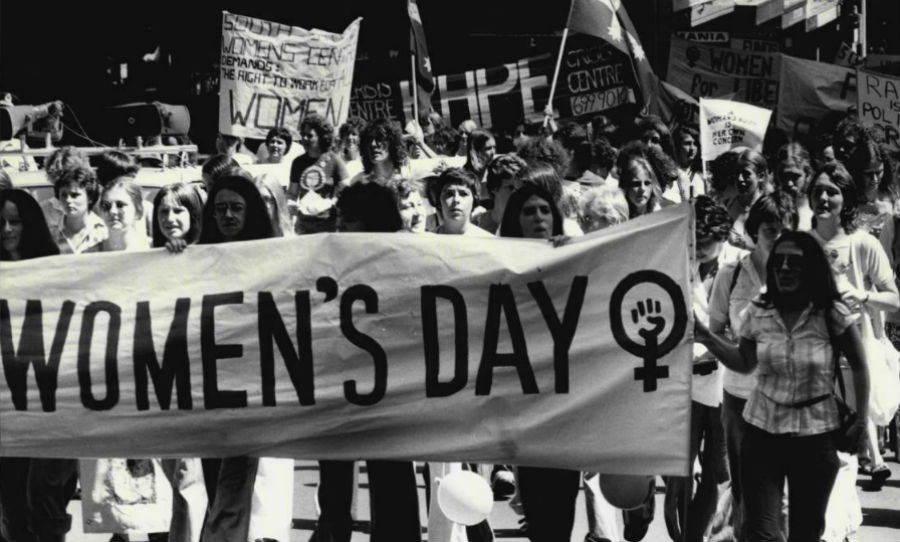

Perhaps the most powerful way to instigate social change is through protest. It’s been happening for centuries – one of the first instances of modern protest occurred in 1215 when English serfs resisting authority appropriated King John’s Magna Carta. Relentless struggles against those in power – whether they’re people, laws, groups or doctrines – have the power to bring about grassroots social change.

Women have been protesting all over the world since the dawn of time. Stories of women and non-male identifying individuals fighting against capitalism, the patriarchy and gendered social injustice are powerful and heartbreaking simultaneously.

The earliest observance of International Women’s Day occurred in New York City in 1909. It is now held annually on March 8, coinciding with the anniversary of the day women gained suffrage in the Soviet Union. With its roots lying in anti-capitalist, anti-bourgeois and socialist ideologies, IWD has since become a day of celebration for women the world over. In some countries it is a public holiday, in others, it’s a day of remembrance.

In the wake of International Women’s day, we’re taking a look at some of the most powerful feminist protests from around the world.

China’s Feminist Five

China’s Feminist Five were arrested on the eve of International Women’s Day in 2015. Li Maizi, Wu Rongrong, Zheng Churan, Wei Tingting and Wang Man became international symbols for political resistance. Authorities jailed the activists for handing out stickers against sexual harassment on subways and buses. Condemned in their homeland, the group were celebrated worldwide for their bravery.

China’s younger generation of feminist activists poses the greatest threat to China’s authoritarian regime. They’re national symbols of resistance; feminism is only a recent phenomenon in China but the Feminist Five are advancing the cause in leaps and bounds.

Most recently, Chinese feminists – amongst who were members of the Five – appropriated the #MeToo hashtag on Weibo and WeChat to suit the country’s strict online censorship policies. Chinese men and women took to using the emojis for “rice” (mi) and “rabbit” (tu) instead, in a bold attempt to evade internet censors as both platforms had banned the word feminism from their searches.

Some of the activists have been exiled from their native China, but it seems as though feminism may be starting to catch on. More and more Chinese women are actively choosing to reject traditional norms – heteronormative marriage, childbearing and domesticity – and are pushing the boundaries of feminist existence in one of the most politically archaic countries on Earth.

Pussy Riot

Perhaps the most internationally recognised feminist activists of the 21st century, Pussy Riot was founded in 2011 in the Russian city of Moscow. The group gained momentum after five of its members staged a public protest in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior which was deemed “sacrilegious” by Russian authorities and resulted in detainment and, for some members, a sentence of two years imprisonment.

Prison did not stop Pussy Riot from continuing to protest against the rise and reign of Vladimir Putin and other Russian Orthodox Church leaders. The group gained support from countries and human rights organisations in the West and were prematurely released from detainment, having only served a year of their sentence.

Pussy Riot merge punk music, avant-garde theatre and performance art in their guerrilla stage shows. They’re often seen in costume, donning brightly coloured balaclavas, tights and dresses, even in the bitter cold of winter.

In 2018, Pussy Riot members disrupted the World Cup Football Final in Moscow and were sentenced to serve 15 days in prison. The protesters invaded the pitch donning police uniforms during the match’s final moments. They called for the release of political prisoners, the termination of online and social media censorship in regards to citizen’s political views, the end for illegal detentions at political rallies and for more even and open political competition.

FEMEN

Founded in Ukraine but majorly based in Paris, FEMEN became infamous for their controversial, topless protests against sex tourism, homophobia, religious institutions and sexism, amongst other nationally and internationally recognised inequalities in public places in many major European cities.

FEMEN describes itself as “fighting patriarchy in its three manifestations – sexual exploitation of women, dictatorship and religion“. They’re utilising “sextremism”, a term the group coined, to protect women’s rights in Eastern Europe and abroad.

FEMEN is not shy of controversy, both good and bad. Activists are regularly detained by police forces in response to their protests, which more often than not include members demonstrating in either skimpy or erotic clothing.

Ukrainian feminist Anna Hutsol was credited as the founder of FEMEN after she was made privy to the fact that many Ukrainian women were being coerced into going abroad and, in turn, being taken advantage of emotionally, physically and sexually. The 2013 documentary Ukraine Is Not A Brothel, however, exposed Ukrainian man Viktor Sviatsky as leading the movement. FEMEN member Inna Shevchenko has since taken over the cause, relocating the organisation to Paris and actively protesting the political and economic corruption that plagues many European countries.

Lavender Menace

During a meeting of the National Organisation for Women (NOW) in 1969, feminist writer Betty Friedman used the term “lavender menace” to describe a minor schism of the women’s liberation movement who demanded equal and respectful treatment of lesbian and queer women. Friedman believed this sect posed a threat to the economic and social equality feminists were fighting for because their cause was too niche; lesbians, she believed, did not represent the greater portion of women fighting for equal rights in America in the 1960s.

The exclusion and oppression of lesbian feminists and those questioning heteronormativity were the impetus for groups like Lavender Menace, who used their anger and confusion about being disregarded in the plight of their sisterhood to their advantage. They ironically took their name from Friedman’s quote and begun fighting and campaigning for intersectional feminism, not just cis-and-heteronormative white feminism. Lavender Menace formed in New York in 1970, and many of their members were also involved in the Gay Liberation Front and the National Organisation for Women.

The group infamously interrupted the 1970 Second Congress to Unite Women, which excluded any lesbian and queer rights issues from its agenda. The team cut the lights at the Congress, and when they came back on, a group of women donning shirts that read “LAVENDER MENACE” walked around the room and handed out a manifesto they’d called The Woman-Identified Woman.

Sekirankai – The Red Wave Society

Founded in 1921, Sekirankai – or The Red Wave Society – was a Japanese socialist women’s collective who actively condemned capitalism, promoted anarchism and disturbed the order of the Japanese class system for the time that it existed.

Prominent Japanese feminists Yamakawa Kikue and Noe Itō claimed advisory of the group, which was the first women’s socialist association in existence. The group was comprised of 42 members, 17 of whom were active, and sought to overthrow the capitalist regime that had taken over Japan in the early half of the twentieth century.

The group’s first foray into activism was the May Day protests of 1921. A day adopted by Japanese socialist and communist groups in response to International Worker’s Day, May Day saw members of Sekirankai distribute copies of the manifesto that Kikue had drafted prior to the event. Titled Fujin ni Gekisu (Manifesto to Women), the manifesto condemned capitalism for engendering imperialism and framed capitalist issues from a feminist standpoint.

Sekirankai was also infamous in their native Japan for conducting lectures on socialist feminism and the crises of capitalism. In the latter half of 1921, members of Sekirankai held a five-day seminar to educate people about their cause. They published the magazine Omedetashi (Auspicious Magazine) and began to distribute anti-war leaflets to the army through the mail.

The group, who framed feminism through a Marxist lens, disbanded by the end of 1921 because of new laws enforced by the Japanese government who began to prohibit women from attending political meetings and joining political organisations. Although the organisation was short-lived, the ideals behind Sekirankai came to forge many of the spin-off socialist and anti-capitalist groups of Japan to the present day.