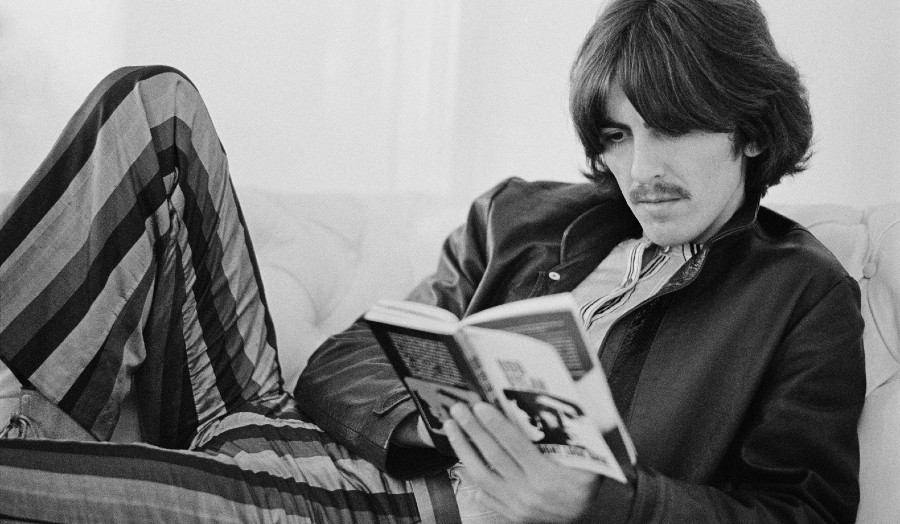

A seventh-generation Muslim Australian who went to art school, Abdul Abdullah has embraced the title of outsider. Sometimes that pisses people off.

Abdul Abdullah is an artist whose sculptures, photographs, and paintings have transitioned from Australian galleries to the world stage in a short number of years. His modus operandi was originally examining the experience of young Muslims in Australia, but as his profile has grown, he’s found the need to expand his messaging beyond a local scope.

He’s also a self-confessed outsider, in more ways than one. It’s probably why I asked him about it so damn much.

For our Issue 13 cover interview, we sat down with Abdul in his Sydney studio to chat about the dangers of romanticising art, how the purpose of his work has changed, and – quite basically – what the hell an outsider actually is.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 13. Pre-order your copy here.

HAPPY: You’ve called yourself an “outsider amongst outsiders…”

ABDUL: I thought that’s where we’d start.

HAPPY: Believe it or not, I read that on your website after we asked you to do this. Seems like we picked the perfect person. What did you mean by that phrase?

ABDUL: It’s meant a few different things over the course of my career, or creative pathway I guess. When I was growing up I was part of a Muslim community but all the boys in my family went to art school, and we did all the things that a young person going to art school does. So that made us a bit of a standout in that community. And then when I was in art school I worked in a boxing gym, so I was a bit too ‘boxing gym’ for art school and a bit too ‘art school’ for the boxing gym. These are just little examples, but it’s the idea that artists are outsiders, generally, but then having that identity, being a seventh generation Australian Muslim, puts me on the outside again. So even in this community of Muslims, I’m an outsider in respect to being an artist. Can I keep talking, or should the answers be short?

HAPPY: Go for it.

ABDUL: One of the things I’ve been thinking about recently is you’ll get some very successful Australian artists who have very similar political views to me, and they might be considered the black sheep of the family, in a broad context. But they’re still considered part of the family. I feel in my experience I’ve been treated more as a threat, and I think that has more to do with my cultural and religious identity.

HAPPY: Going deeper into the term itself, what does ‘outsider’ mean to you?

ABDUL: For me, being an outsider is being one who doesn’t fit the broad societal strokes. Growing up I was probably about nine years old when I started thinking of myself as an outsider, and initially it was not seeing people who looked like me or had names like mine reflected or having their stories presented in the mainstream discourse. If you turn on the TV, if you watch any of the soaps, if you watch any of the reality shows, there was no one that represented my story, or anything that I really related to on that base level. That was the initial experience of being an outsider, for me. Then after 9/11, the experience of being a Muslim in Australia and the vilification of Muslims in Australia, that was very… well, it was a stark difference in the perception of what an outsider is for me.

HAPPY: I think the way that you look at it, and what we’re finding through exploring this topic, how most people think of being an outsider is actually quite different to the classical definition of what you’d call ‘outsider art’ or ‘outsider music.’

ABDUL: Yeah, because I think most artists or most musicians are outsiders naturally, in one sense, but then insiders in their own world. I’d say I feel like an insider in art world stuff, but an outsider more generally.

HAPPY: Do you think outsiders are romanticised?

ABDUL: That’s an interesting question. Yes and no? But I think that’s the answer to most questions. A little bit of column A, a little bit of column B, in some cases they are and in some cases they aren’t. Especially in hindsight, I think they are, but the experience of being an outsider is not necessarily a pleasant one. Maybe in a voyeuristic point of view it’s an exciting thing, especially when you look at musicians and artists. But their lived experience is probably pretty horrible.

HAPPY: That’s what I think, it can be a dangerous form of romanticisation. ‘Outsider’, back to that classical definition, sometimes just means ‘had a mental illness.’

ABDUL: Totally.

HAPPY: Do you think someone can be an outsider without some form of marginalisation?

ABDUL: I think there’s an outsider in each of us, to sound pretty naff! When I was initially producing work that wasn’t just pretty pictures of my friends – and that’s how I really started – but when I started to have a political context to my work and really began exploring things outside of just faces, I was really concentrating on the experience of young Muslims in Australia. But I found that work was pretty poorly relatable, especially with young people. I get a lot of emails from high school students who are not necessarily seeing themselves fitting into certain expectations; whether it’s being put on by other people in their social group, or a broader social group, or from their family even, they relate to the conversations I’ve been having or some of the ideas that come through in my art. So it’s not necessarily a marginalised experience all the time, although I think that’s largely it, it’s a sense of yourself and a perception of yourself related to how other people perceive you.

HAPPY: You said introducing politics, or some sense of contentiousness, into your work was when you really started. Is that kind of push/pull necessary to being an artist?

ABDUL: I don’t think that push/pull is necessary to everyone, but for me it is. For me to produce the work that I want to produce, I have to be interested in it, and for it to be interesting it needs to have that. It’s got to have a lot of grey area, have a lot of good and bad, it’s got to have some sharp points, otherwise… honestly I just get bored.

HAPPY: Where does your audience fit into that picture? Are the sharp points for you or the people who are viewing them?

ABDUL: I think they’re both for myself and my audience. I used to host an arts program on FBi [Radio], and one of the really mean questions I’d ask – well, people thought it was mean but I thought it was a good question – was I’d ask “who’s your work for?” And it’s even slightly different to “who’s your audience?” It’s about who you’re making your work for and who does this work serve? I think too often artists neglect that. I’ve kind of gone off the question, but when I think about who my work serves, it has become about that nine-year-old version of me who’s just discovering that their experience has not been one that’s related to them in other forms of media. And that has expanded to those nine year olds around the country, those teenagers and young people around the country who are all relating to that similar experience of being voiceless or being marginalised.

HAPPY: I think that’s quite interesting because a lot of people would look at your work and think, on a very basic level, that you’re trying to make people angry.

ABDUL: Yeah, I’ve had that. Say my artwork in the Wynne Prize was a landscape that said “A TERRIBLE BURDEN” on it, and it was described to me as a stunt, or I made this work that said “WHY CAN’T I BE ANGRY” and people thought I was deliberately trying to be provocative. But that’s not what I was thinking, the work isn’t about poking the people who would disagree with me, but serving people who relate to that experience.

HAPPY: You don’t seem like an angry person.

ABDUL: Nah, I don’t think so. When I was younger, potentially.

HAPPY: Has the reception of your work changed since you moved into the fine art space?

ABDUL: Definitely. How do I put this? To alter the question a little bit, my practice has changed since I shifted from an entirely domestic audience to more of an international audience. Now half my shows have been overseas and the conversations I’ve been having in these settings are a little bit different to the ones I’ve been having in Australia, and the politics are a little bit different. So I’ve found that I speak with broader strokes and I speak more to the heart of things, or more to the motivating emotions rather than particular and specific political events. Does that make sense?

HAPPY: It does, I was actually going to ask about that. Australia has turned into quite the canvas for these topics that you talk about. But you’ve started exhibiting overseas, so you’ve found yourself opening things up more?

ABDUL: Yeah, more broadly. The core of the themes that I’m looking at are broadly relatable, but I can’t necessarily make work that reacts to something like the Cronulla riots.

HAPPY: Has that been a challenge?

ABDUL: Yeah, it’s been a matter of pulling the specifically Australian signifiers out of the work, but they still may feed directly into why I make the work. For example, some of my most recent series, the genesis of the idea was a poster put up by the Australian government in Indonesia. It was an ocean scene with a crashed boat that said “if you arrive in Australia by boat you will never be settled here, regardless of your refugee status.” That was the beginnings of the idea and that was what I was thinking about when I made the work, but if you came to that work without seeing that specific image, it didn’t matter. It still spoke to that idea of overcoming obstacles, whether they be an ocean, a government, or personal obstacles. It was open to interpretation.

HAPPY: You’ve been forced to distill your own ideas.

ABDUL: Distilling is a great word.

HAPPY: What came to mind just now was Arielle Gamble and All We Can’t See [an exhibition of artistic works relating to The Nauru Files in which Abdul took part], which was distinctly Australian, but could be extrapolated to the whole world.

ABDUL: Absolutely. Those works with Arielle’s show were specifically talking about The Nauru Files and the Australian government’s responsibilities, and what we were doing in Nauru and still doing, but the works themselves… they could be read in all sorts of different contexts.

HAPPY: What are some things that you’re working on now?

ABDUL: I’m expanding on these ocean scenes, and I’m elbows deep at the moment into a 12-metre painting that will be at The Armory Show in New York in March. It’s a giant wave break with these white cartoon-y figures over the top, which will speak to the idea of tension – a friendly tension or a competitive tension – between two different groups. I’m not sure exactly what that’s going to look like yet, but that’s what I’m thinking as I’m starting to draft these ideas.

HAPPY: Something I wanted to ask is, outside of getting these commissions from overseas or getting interviewed by a magazine, how do you measure your growth as an artist?

ABDUL: That’s another really tricky question! What do musicians say when you ask that?

HAPPY: I actually don’t think I’ve asked a musician that before, but I might start now. Instinct says it’s more about the personal side of growth, which is trickier to measure, of course.

ABDUL: Measuring personal growth is really, really challenging and difficult. I could measure growth by how many opportunities I’ve had to make and show work, or to engage in conversations which I wouldn’t have had otherwise. I could look at my platform and how that’s expanded, and how that expansion has influence in a strange way like giving me access to areas that I wouldn’t have had access to before. One of the things I’ve always said is that as my practice builds and my platform builds and enough people are listening, I want to have something really good to say. But I’m still working on what that is (laughs). As far as how I measure it, one of the things that I really enjoy, and I keep talking about young people, but getting an email from a young person – mostly high school students doing assignments, which is nice – where they’ve said that a particular work has spoken to them in a way that I’d intended it to. So that is a really, really nice experience.

HAPPY: Does that feed back into what you’re doing now?

ABDUL: It definitely does. When I’m talking about access, I’m not necessarily just talking about access to exhibition opportunities or those different spaces – for lack of a better word, those ‘elite’ spaces – but also access to a generation that’s coming after me. Access to other people and access to conversations and beliefs and interests. For example, I was up in Lismore recently on an outreach program… that’s work but it’s also an opportunity for me to engage with young people at risk. There’s something really rewarding in that, and I wouldn’t have had that opportunity if this other art stuff wasn’t working well for me. That stuff is good for the soul.

HAPPY: To ask a few questions about this space, how long have you been in this studio?

ABDUL: I’ve been in St. Leonards for two years, and it’s a really weird place. I mean it’s a strange suburb, lots of great lunch spots, but very office-y.

HAPPY: What have your work spaces been like before this?

ABDUL: Before I was in this studio in Sydney, I was in a warehouse in Alexandria, which was really good. There were 22 artists there. But then one day a collector came to visit one of the artists and they liked the space more than the art. We were all out in a couple of months.

HAPPY: Shit.

ABDUL: That seems to be a recurring thing, so it’s good to have this space for at least a couple of years.

HAPPY: Is this the first space you’ve been in by yourself?

ABDUL: In Perth I had a home studio, but this is the first studio that I go to that I’ve got to myself. It’s really awesome having this space. It’s pretty lonely, to be honest, but it’s like having a little kingdom to do with as I want.

HAPPY: Sorry if I’m prodding here but that lonely feeling… when I look around at a few pieces here, I can really see that. Can that help, getting yourself in that headspace?

ABDUL: I’ve never thought about it like that, and I can see how it would help… especially over the last few years working in this particular space, I can see how that makes a lot of sense. But I think that working in a more communal space also has a lot of really good benefits.

HAPPY: Collaboration…

ABDUL: Motivation, people around. I spend much less time on my phone when there are other people around. Half the reason for having assistants is just having someone in the studio so that I’m not fucking around too much.

HAPPY: You need a watchdog!

ABDUL: Yeah, so I’m at least accountable to somebody.

HAPPY: Where do you keep the hate mail these days?

ABDUL: Honestly, I get less and less of it, which is interesting. I just think there are more people, and there are more prominent people who that hate mail gets focused on. Friends of mine, too, cop it a lot worse than I do or ever did. And now it’s only very rarely and only in response, generally, to when there’s something in the major papers. Otherwise, I’m largely ignored by that part of society. I have a separate email for responding to those.

HAPPY: What would you call the ultimate goal of your work?

ABDUL: That’s another really hard question. When I was in art school my ultimate goal was just to live as an artist, and I’ve been doing that for a few years and really enjoying it, so that goal keeps shifting. Even a year ago if you’d asked me, the answer would have been different. Maybe it’s just cynicism coming through but I just don’t currently have one. Like, saying if I can have a lasting positive contribution to a cultural discourse, that would be really, really nice, but at the end of the day, when I’m dead it doesn’t matter. So I don’t know, man!

HAPPY: Maybe people will remember you as an outsider and your prices will get jacked up tenfold.

ABDUL: That could be really great! But if I can help a young person deal with or articulate some of the shit that they’re going through in their own lives… I’ll never be able to measure that, but if that were to happen, that would be the best.

HAPPY: A noble goal.

ABDUL: Yeah, I’d like to have a noble goal. Then buy a Land Rover.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 13. Pre-order your copy here.