The ’60s were a time of mass civil resistance and free love. To recap the era we’ve collected the best non-fiction books of the decade.

The best non-fiction books in the ’60s were informed by the historical events of the decade. The Civil Rights movement, the beginnings of second-wave feminism (that would later explode in the ’70s), and more. All of these major socio-political events led to the 1960s being marked as one of the most divisive and revolutionary decades in history.

Taking into account the fact that the ’60s were more than half a century ago, we’ve made it easier to catch you up to speed on the major cultural touchstones of the era by collecting the best non-fiction books of the decade, below.

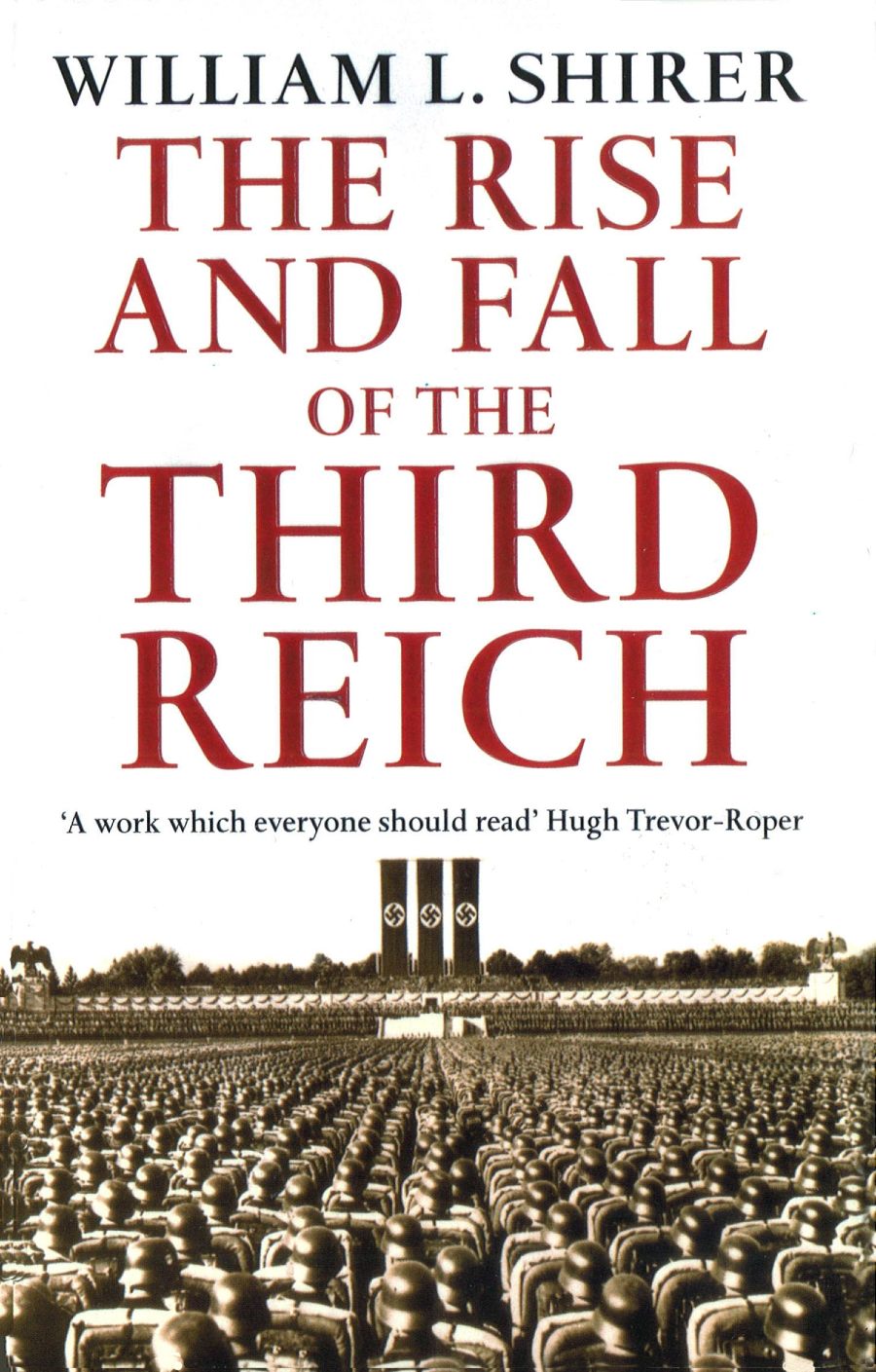

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich – William L. Shirer (1960)

Chronicling the rise and fall of Nazism, the book is based on captured Nazi documents, the diaries of propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, of General Franz Halder, and of the Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, evidence from the Nuremberg trials, British Foreign Office reports, and William Shirer’s own recollection of his six years in Germany as a journalist covering the rise of Nazi Germany. Winning the National Book Award for 1961, the book received critical acclaim in America, whilst receiving mixed reviews abroad for its interpretation of Hitler’s ascension to power.

The Australian Ugliness – Robin Boyd (1960)

Written by Australian architect Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness is a critique of the visual pollution of in the Australian architectural aesthetic at the time. While described as unpatriotic by mainstream Australian media when it was published, Boyd’s non-fiction book has become one of the most important books in the history of Australia’s architectural landscape, and has facilitated debate in Australia about design, architecture and urban planning.

The Feminine Mystique – Betty Friedan (1963)

Described by The New York Times as “one of the most influential non-fiction books of the twentieth century,” The Feminine Mystique was a book that revolutionised the way the public perceived feminine gender roles and domesticity.

It discusses “the problem that has no name“— the term coined by Betty Frieden to describe the widespread unhappiness of women in the 1950s and early 1960s. Split into fourteen chapters, it shows how domesticity and traditional gender roles can result in the erasure of women’s identities. It was credited with facilitating the birth of second-wave feminism, in particular, drawing many middle-class white women to the feminist cause.

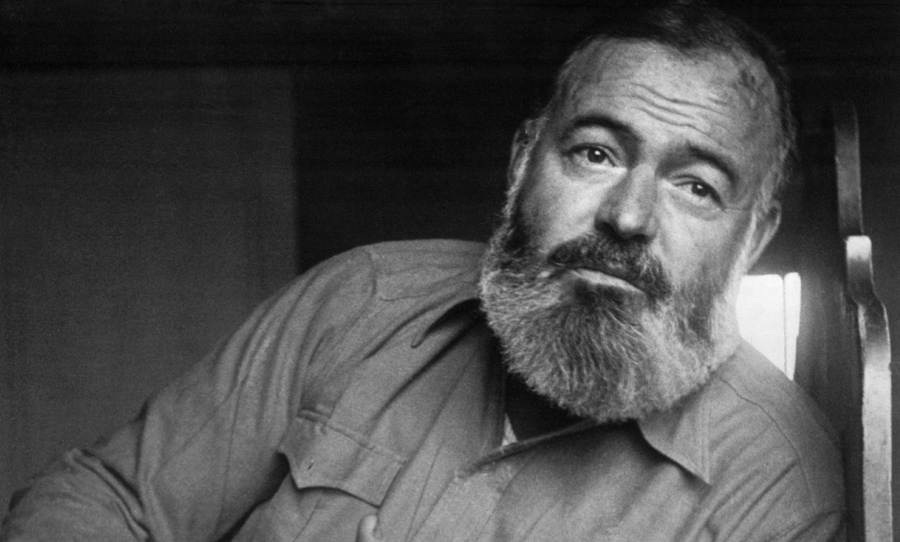

A Moveable Feast – Ernest Hemingway (1964)

When you think of Ernest Hemingway — “struggling writer” isn’t generally the phrase that comes to mind. But even the great artists had to start somewhere, and the posthumously published A Moveable Feast tells the story of Hemingway in this exact position.

The non-fiction book details his years as a struggling ex-pat journalist and writer in Paris during the 1920s, his first marriage to Hadley Richardson and his associations with other notable cultural figures of the time (e.g. Sylvia Beach, John Dos Passos, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, Pascin, Ezra Pound, and so many more).

The Lucky Country – Donald Horne (1964)

The Lucky Country is an awesome take-down of Australian politics in the ’60s. It speaks of a country rooted in mediocre economic policies and intellectual vacuity, with Horne taking Australian society to task for its “philistinism, provincialism, and dependence.” Instead of describing it to you, I’m just going to leaving one of its opening lines here: “Australia is a lucky country, run by second-rate people who share its luck.” You can see why it caused such a sensation upon release, while simultaenously as carving a place for itself in history.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X – Alex Haley and Malcolm X (1965)

A collaboration between human rights activist Malcolm X and journalist Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X is a non-fiction book that details Malcolm X’s philosophies of black pride, black nationalism, and pan-Africanism, that informed his political ideology. Largely responsible for galvanising much of the younger public who attended civil rights demonstrations in the late ’60s, The Autobiography of Malcolm X is one of the most prolific, influential non-fiction books on a man who changed the course of history.

The Diary of Anaïs Nin Vol. 1 – Anaïs Nin (1966)

Anaïs Nin was a French-Cuban-American diarist, novelist and writer of short stories and erotic fiction. at the time of publication, her diaries became best-sellers among young women and established her as a feminist, literary icon in the Americas. She began writing the diary entries at age eleven in 1914 during a trip from Europe to New York with her mother and two brothers, they would continue to keep her company until her death in 1977. Published in 1966, the first volume details life in Louveciennes with her first husband, as well as her introduction and subsequent affair with Henry Miller.

The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences – Michel Foucault (1966)

As described by French scholar Michel de Certeau, “The Order of Things sold out within a month after it first appeared – or so goes the advertising legend. The work numbers among those outward signs of culture the trained eye should find on prominent display in every private library. Have you read it? One’s social and intellectual standing depends on the response . . . Foucault is brilliant (a little too brilliant). His writing sparkles with incisive formulations. He is amusing. Stimulating. Dazzling. His erudition confounds us; his skill compels assent; his art seduces…”

The non-fiction book is known to propose that periods of human history are characterised by epistemes — ways of thinking about the world and concluding truth, also a term that’s synonymous with the Greek root word epistēmē (“knowledge”) — and goes into detail to determine the structures of knowledge that scientists apply to their subjects.

Photo: Amazon

The Double Helix – James D. Watson (1968)

An autobiographical account of one of the most important biological discoveries of the modern era — the double helix structure of DNA — The Double Helix details scientist James D. Watson’s journey in discovering the biological structure with co-scientist Frances Crick. While the non-fiction book won the Nobel Prize for Literature, it wasn’t exempt from controversy or criticism — there’s been much debate in scientific and literary communities about the sexist omission of fellow female scientist Rosalind Franklin, and her significant contributions to the discovery of the structure.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem – Joan Didion (1968)

In a New York Times Book Review, Joan Didion’s non-fiction book was described as “[bringing] together some of the finest magazine pieces published by anyone in this country in recent years. Now that Truman Capote has pronounced that such work may achieve the stature of ‘art,’ perhaps it is possible for this collection to be recognized as it should be: not as a better or worse example of what some people call ‘mere journalism,’ but as a rich display of some of the best prose written today in this country.”

Slouching Towards Bethlehem follows the author’s life as she lives as a writer in California, and is a collection of previous columns written for Vogue, The Saturday Post and various other publications, and upon publication, was widely critically acclaimed for its discussions of social fragmentation and the realities of the counterculture movement.

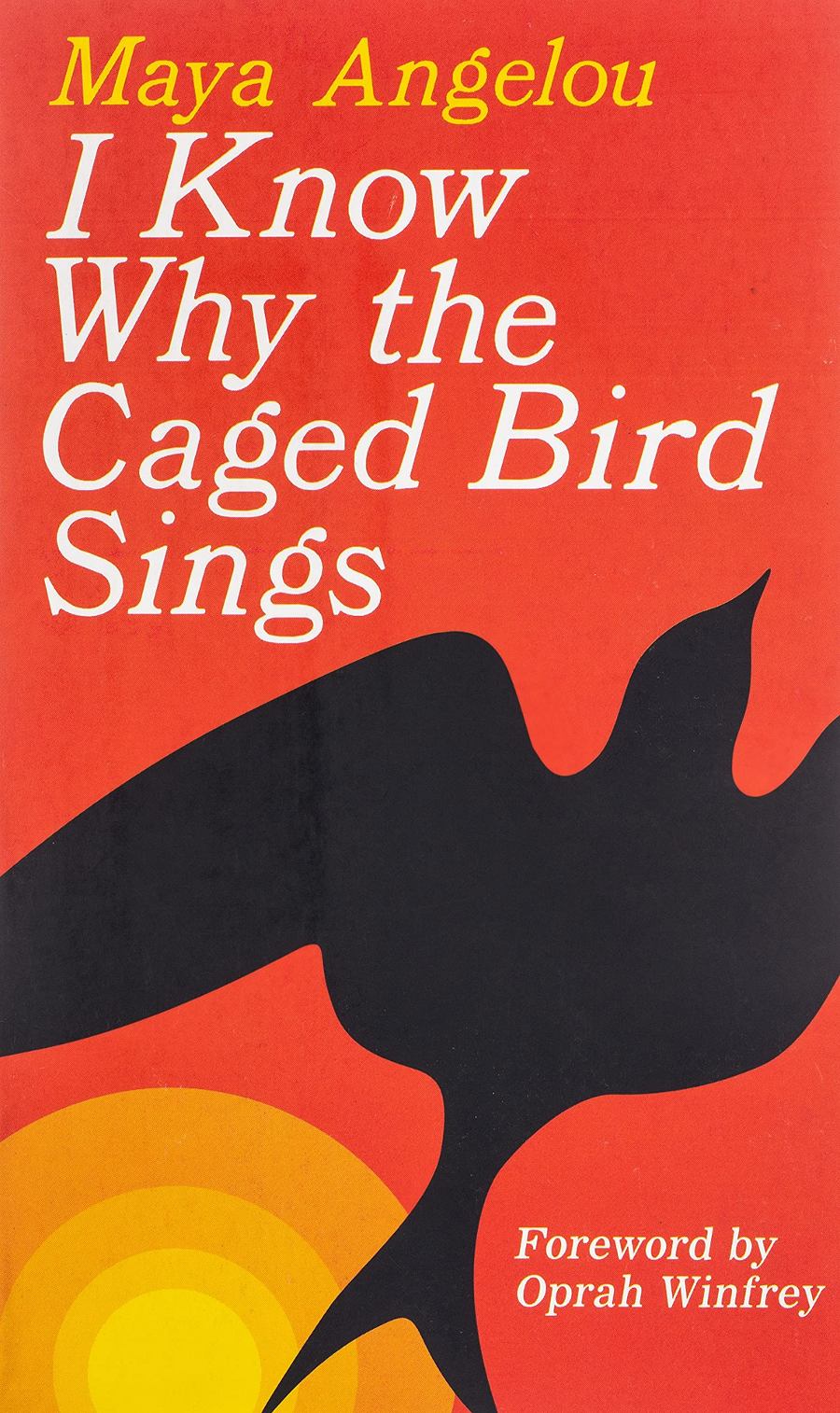

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings – Maya Angelou (1969)

Joyous, yet heartbreaking, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is an autobiographical account of Maya Angelou’s early childhood and adolescence in Arkansas. It functions as both a love letter to the power of literature in overcoming social trauma, as well as an indictment of racism, and a celebration of Black womanhood.

The non-fiction book came about from a challenge posited by mentor James Baldwin, as well as editor Robert Loomis, who dared the established civil rights activist to write an autobiography as a piece of literature. One of the most enduring examples of African-American literature, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is a stunning account of a woman’s struggle for Black identity in the early 20th century.