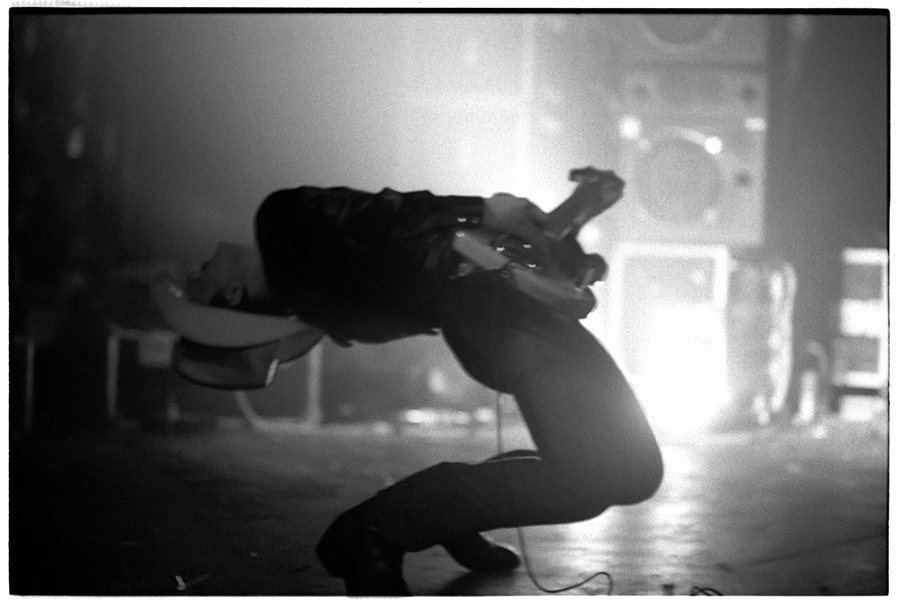

HAPPY: I think those things weigh into your photography though. Your gig shots, that’s a social thing. You mentioned The Triffids, they’re Perthonalities. How was it photographing them and working with them?

BLEDDYN: That was quite different from The Birthday Party. I had something of a reputation by the time The Triffids came to – I went to the same school as David [McComb], but I’m much older than him, he was still in primary school when I left. He actually first wrote to me before he came to England. He sent me the two records they had out then, and I was very pleased to be able to say “already got ‘em mate so I’ll give them to someone else at NME”. He was very pleased about that, and they arrived and travelled as a band. David was much more organised – he’s kind of like Nick and Mick Harvey rolled into one, if you know anything about those personalities. He was the guiding principle in that band always, it was always his band. I met him within five days of him landing in England and I liked him immediately. We just got on forever, until he died basically.

Yeah, they are different, they’re much more disparate. David’s actually very like Nick, he just has a different upbringing. He’s the youngest in his family, he was always reading and listening to music and was always a full bottle about everything. He’s like a lot of musicians, he’s a real consumer of music so he was wholly across everything that was happening. For someone with similar obsessions, he’s easy to talk to, there was always a million things to talk about, and to disagree, like Nick, they don’t agree with you but they actually like arguing and saying “oh no that’s shit”, just like friends do. But why is he West Australian? He definitely had that sense that you get in Perth from being away from the rest of the world, of being right on the other side of the world.

My whole family still lives there, I’m the only one who left. I don’t like it, and I feel trapped there. I’ve driven across the Nullarbor six or more times. I’ve obviously flown millions of times now but when you’re 20 you have no money and you’re at uni. You don’t have any support from your family which I didn’t, then you have further difficulties, in Perth you have to have a car. The public transport is just the railway or spending an hour and a half on two buses to get anywhere. It was always a great deal of laborious boredom to deal with. Living in London, people can live as far away from you as they might live from you in Perth, but you didn’t have to have a car because you got the Tube, which you can read on so you can kill two birds with one stone. I had to go to a school on the opposite side of the [Swan] River, which was two buses everyday, a three-hour commute to go to school. When I left home I moved north of the river, you just got sick of having to take 90 minutes to get somewhere all the time.

HAPPY: When did you end up leaving London, if that’s where it was all happening for you?

BLEDDYN: In 2006.

HAPPY: To Perth or Sydney?

BLEDDYN: My wife Judy got a job out in Sydney which is why we came back, she knew that I would never voluntarily move back. She worked for an English television station and she put her hand up as soon as she heard they were opening an office in Sydney. They decided she would be the best person to do it. We always came back and we were gonna move back here in ’93 because Judy had enough of England. Our kid got a scholarship for high school, otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to afford to pay the fees, so that’s the reason why we stayed there. By 14 he was not wanting to visit Australia anymore. It’s just not like me – Jim Fisher’s the only friend from high school left, and it’s mostly friends from university or people like Dave Warner who I know from Perth, Terry Serio. Other than that they’re all people I met in England, but a lot of them are Australian. That’s the weird thing, a lot of people I call my friends are actually Australian musicians who came to London in the ‘80s.

HAPPY: Was there any shift in your photography work or the way you started approaching it after being in London for so long?

BLEDDYN: When we moved back I had to finish writing the book about David and The Triffids which took two years. So, I didn’t immediately have any sense of it at all because I wasn’t actually taking photographs at that time. But after that there was a definite shift. If you can sum it up in one word, it’s ‘digital’, which actually changed the whole world. It devalued photography as a profession, a whole lot of magazines just ceased to exist because the advertising disappeared. One of the great things of working for NME was I basically got to meet a whole lot of people I would never ever have met or been asked to do work for. No matter how big an article was in NME, they always wanted their own photographs. It’s luck of the draw, some of those people weren’t worth meeting or didn’t go on to have careers or were just playing in bands for a year and a half and didn’t get anywhere and gave up. By the same token I met a lot of my closest friends from that.

But that culture doesn’t seem to exist anymore. Did it change my approach to photography? I realised that I had to work for myself and generate everything myself which is a part of what the Plague Doctor cards are about. My friend Brian Waldron was making masks and downloading the patterns from the internet. He wanted me to take pictures of them. He made a dog, a bear, and a crocodile. I kind of said, “yeah well, these are just photos of you with a stupid mask! Can’t we do something that we can turn into a character?” He suggested the dog but I said that there’s no literary resonance, there’s no meaning in a dog. He then suggested the crow and I said, “yeah! That one’s a plague doctor let’s do that! Can you make the hat as well?”

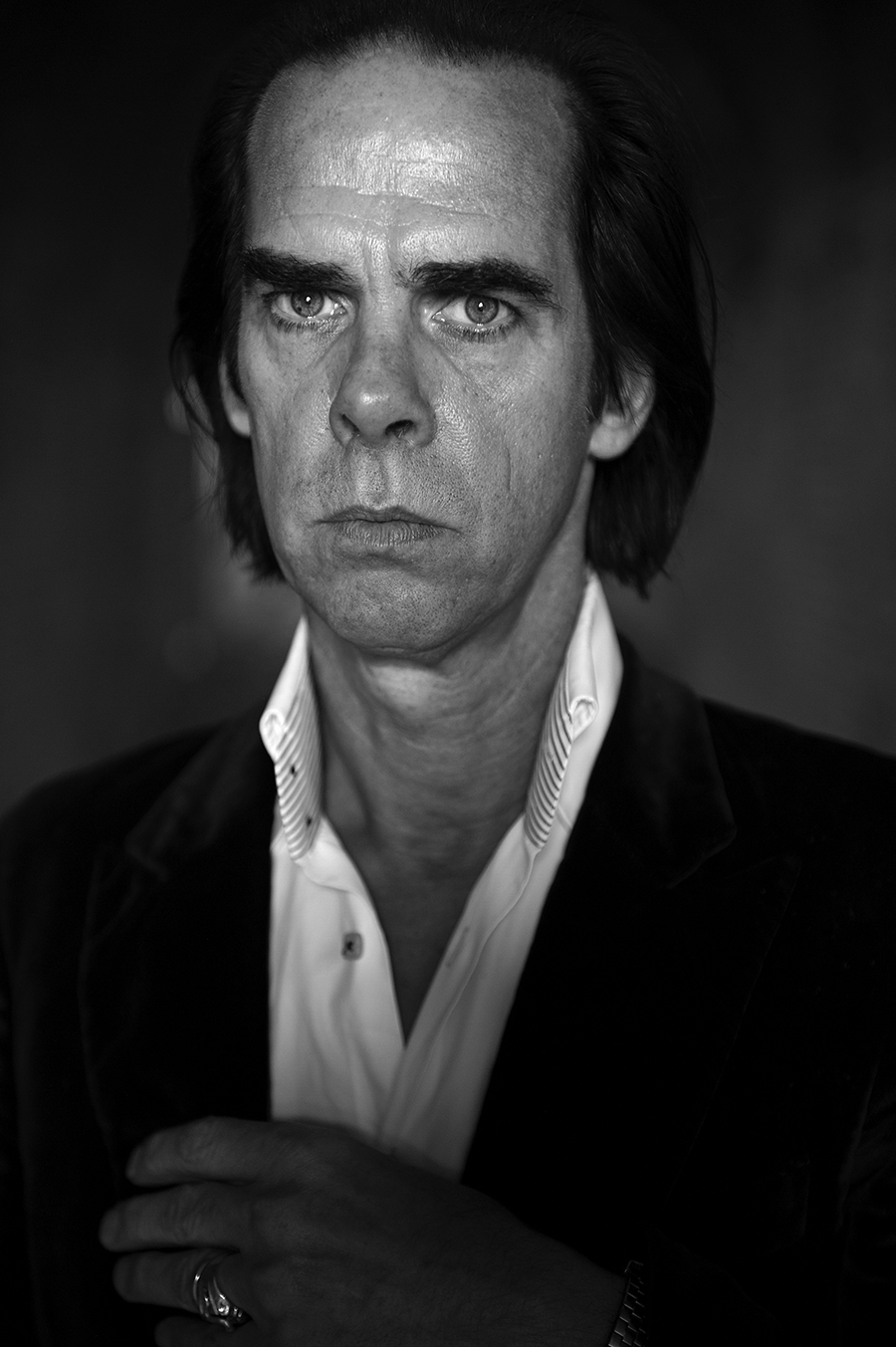

This was last March, the first two weeks of the pandemic. I just thought, we can do this because we can be serious, we can be funny, we can be stupid. There’s a whole lot of things we can do. And we can travel around so some of it can be political, some of it can just be a joke. And so I realised I was gonna have to work for myself and generate my own subject matter. That’s what I realised when I came here. Before this, I realised my subject matter is my friends, the people I really respect in music. Then I realised that my fascination, or my interest in Nick for instance, has actually lasted so long that I could do a visual biography.

HAPPY: Yes, there’s this unique rapport between you two. What was your bedside manner with Nick to be able to achieve that?

BLEDDYN: It started because I was a fan and a big time supporter of what he did, I came to England in 1980 just like they did. I met them through Chris Bailey from The Saints. When I was at NME, people weren’t interested. It’s hard to conceive of now. I was constantly saying, “he’s just got a new record out, it’s really good”, those sort of things a fan boy says. You have to think about what’s contemporary. What was contemporary in 1982 to ’83 was Duran Duran and Culture Club. I sort of went, “yeah that’s all good pop music but will it last? I think what he’s doing will last”, which turned out to be true, I was lucky to bet on red and red came in.

It started out with me being an advocate and the payoff for that was that I would get to do the photos. It took him a while to actually give in. It took four months to persuade him to do the photo that’s supposed to be, or that he really likes, the famous one of him in that cluttered room we made together in Berlin. The idea of that was he’d given me an early draft of his first book, the novel he wrote, and I wanted to do something whereby he was pretending to be the character because it would give us a background and a setting. There was one failed photo session which was kind of hilarious, he was stoned as he always was in those days. I wanted to take him out into the woods and take flash photos in the woods so that the leaves would catch the flash light as well as him. But he wasn’t very interested in posing – that thing I said about posing – when he’s not interested in posing, he just looks stiff and shithouse, he just looks awful. He was very nervous in front of the camera.