We occupy an age where knowledge about the recording studio is abundant. Yet it was a few short decades ago where this was definitely not the case. The pioneers and unsung heroes that honed these records often made (and broke) the rules as they went along.

Subsequent generations of studio folk have benefited greatly from their service and continue to learn from the techniques they established. Below is a list engineers and mixers that may have earned various accolades throughout their stellar careers, but have been overshadowed by more famous contemporaries and have generally remained “behind the scenes” during the rapid development and expansion of the recording industry.

Behind every great record are the engineers and mixers who guide the likes of Elvis Presley and Michael Jackson to greatness. These are the unsung heroes of the studio.

Bill Porter

Porter has been widely credited for cultivating the now world-famous “Nashville” sound. He engineered 150 Elvis Presley songs, many of which achieved chart-topping status, mostly on a now mind-bogglingly limited 3-track tape machine. In the late 1950s and early ’60s however, this technology was state of the art. In fact, such was his prowess at producing top-quality commercial records, 15 Bill Porter engineered records were in Billboard’s top 100 for a week in 1960.

Acoustic spaces in those days were fraught with inconsistencies and Porter had to battle with signal-to-noise ratios that would be considered unacceptable today. In spite of these challenges, he experimented with acoustic treatments and echo chambers – the latter of which was put to good use in tracking hits for artists like Roy Orbison.

The speed at which recordings were completed in this era presented additional challenges to engineers like Porter. A two-day session with Elvis Presley in April 1960 yielded twelve songs and two No 1 singles. Arrangements were often done in the studio and Porter had to be reliable and sharp enough to capture the magic live. This relentless work ethic resulted in a career that spanned approximately 7,000 sessions.

Larry Levine

Few figures are as dominant in the sphere of production as Phil Spector. At his right hand was Larry Levine, the recording engineer credited with making Spector’s “Wall of Sound” a reality. Levine got the gig with Spector by filling in on a session at Gold Star studios, Los Angeles.

In the early 60’s, recording big sessions was difficult. Spector’s vision required tracking multiple guitars, pianos, large percussion ensembles and brass sections. He was also a notoriously difficult taskmaster. Levine’s innovative approach to the echo chamber created space in the sound, elevating potentially cluttered arrangements into the realm of the gloriously massive productions that Spector’s legend was based on.

More than anyone on this list perhaps, Larry Levine epitomises the unsung hero. Ten years older than Phil Spector, Levine was the down-to-earth, technically-minded engineer tasked with bringing Spector’s imagination to life. Plus, he had to deal with his moods! Kudos.

Geoff Emerick

Most of us can recall the name of George Martin. The producer has been rightly recognised as a major driving force behind the ceaseless creative expansion of the Beatles throughout their career. The name of Geoff Emerick however, is somewhat more elusive. He manned the console for some of the Beatles’ more sonically ambitious records toward the latter part of their career: Revolver, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Beatles (The White Album) and Abbey Road.

The impact of The Beatles has often been attributed to the time at which they arrived in the world. Revolution was in the air. Emerick’s employment at EMI at age fifteen, in the same week as the Beatles first recording in the studio, was equally serendipitous. He worked as the assistant to Beatles engineer at the time, Norman Smith, until he was promoted (still only twenty!) to engineer for the Revolver sessions.

Emerick had a creative and daring approach to recording. He even suggested to George Martin that he should record John Lennon’s voice through a Leslie speaker on Tomorrow Never Knows. He flourished under the guidance of Martin and with the support of the band. Emerick continued to work with Martin and the Beatles till late in their career (after a brief hiatus due to tensions in the White Album sessions) and went on to work with Elvis Costello, Split Enz and Jeff Beck.

Bruce Swedien

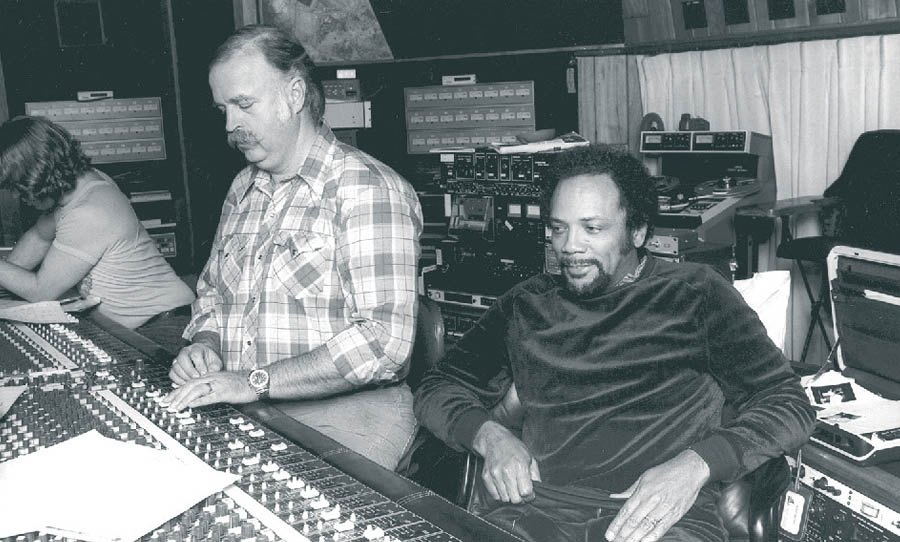

Fast forward a decade, and the recording industry had matured a great deal. Driven by the competitive nature of the charts, studio technology had improved exponentially. Bruce Swedien was one of the true masters of the era, working closely with Quincy Jones and getting the gig for recording Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

Swedien was a recording prodigy – working professionally from his teens and recording the Chicago Symphony Orchestra by the age of twenty-one. After moving from his native Minnesota to Los Angeles to pursue his dream, he teamed up with Jones, who at that time was up-and-coming arranger and producer. Swedien worked with jazz legends like Duke Ellington and Count Basie, and by the time it came to work with the king of pop, he had an established studio pedigree.

Swedien was given carte blanche to make unconventional miking choices in the Thriller sessions, including the use of a Shure SM7 on the lead vocals. He raised eyebrows by using the mysterious “Acusonic” recording process, leading to all sorts of mythology regarding magical gadgets to produce the stunning sound on Thriller.

Swedien was quick to debunk the legends, however, explaining that he simply used a SMPTE time-code to sync tape machines. This had two distinct benefits: it allowed an unlimited track count, which meant Swedien could track overdubs in stereo (a sonic trademark of the album); it also allowed for rhythm section transients to be preserved, rather than being dulled by repeated plays for tracking overdubs. This allowed the rich, multi-layered Quincy Jones productions to shine with the vitality and punchiness that Thriller was renowned for.

Mick Guzauski and Peter Franco

Why two people, I hear you ask? Well, these two guys combined to engineer one of the most celebrated and ambitious albums in recent times: Random Access Memories by Daft Punk. And with a plethora of music industry heavy-hitters such as Nile Rodgers, Pharell Williams, Julian Casablancas and disco legend Giorgio Moroder contributing to the record, Franco and Guzauski are truly the unsung heroes of this project.

Consider the scale of this album. Putting together all these powerful musical forces and egos. It could have all gone so wrong! But it all went very right indeed, and a lot can be said for the consistent, clear-headed presence of these two engineers.

Daft Punk wanted to record with mainly live players on Random Access Memories, which is an additional challenge for engineers, especially when considering the epic nature of the songs. Track counts were huge, sessions were located in France and America: a logistical nightmare. The resulting sound is not as heavily produced as you might expect though, which was in keeping with the concept of the record: bringing back the golden retro sounds of dance music forefathers. Yep, lots of Neumann, lots of Neve!

This list doesn’t represent all of the unsung heroes of recorded history. The selection is compelling because they achieved great results at different points in history, with a common commitment to audio excellence, minus the ego. Who’s to say what could have been achieved if Larry Levine worked with resources that were available for Daft Punk? What if Bruce Swedien had worked with George Martin and the Beatles instead of Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson? The unsung heroes on this list may have had creative guidance from the producers they worked with, but would the records sound the same if they weren’t at the controls? I doubt it.