There’s an addictive quality to Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever that seems best attributed to the fact that they manage to craft such credible worlds with expert precision.

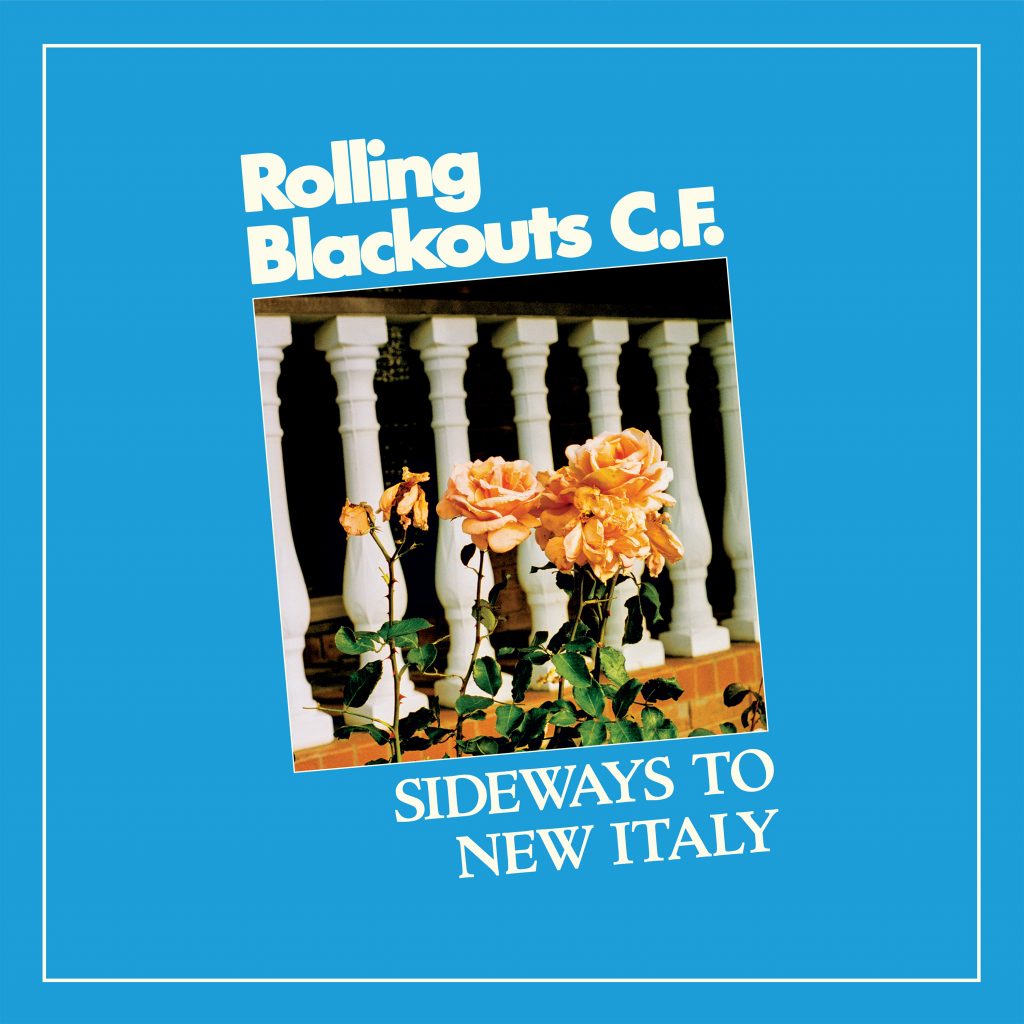

It’s easy to recall the dust of rural Australia between the sunburnt strums of their poetic jangle rock, and on their second album Sideways To New Italy, the Melbourne-five piece retain all their magic, all the while reaching for something to hold on to.

With the release of Sideways To New Italy, we spoke to Joe White of Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever about catching moments in the ever-moving current.

“We put more work into this record than anything we’ve done before,” Joe White described to me ahead of the release of Sideways To New Italy. This is partly because this time around they changed up the recording process and worked with Canadian/Australian engineer and producer Burke Reid (Courtney Barnett, Julia Jacklin, DZ Deathrays).

But it was also something that emerged in the process of creating the album. Rather than writing the songs separately, as they had done previously, the band decided to take more of a collaborative approach: “This time we really tried to just find that little spark of magic in the band room and use a lot of improvisation just to extract some of the best parts of the songs.”

Yet it wasn’t all that simple. White recalls there was a sense of confusion which attended this process, a feeling of “wandering blindly through songwriting.” But ultimately, the outcome was worth it.

“We’ve got a record now that’s kind of unique, and it wouldn’t be the record it is if we didn’t do that,” he tells me. “It just took a long time.”

It’s intriguing to discover that this record that feels so polished, once existed in some kind of disarray. It’s a fact that points to how little we know about the journey a song goes through before the final product reaches our ears. White goes on to describe how it wasn’t until they dived into pre-production with Reid that the songs began to assume what would ultimately become their final form. He recalls how Reid acted as a buffer for their more experimental ideas to do with structure and style, an “advocate for the listener”, who guided the songs towards more classic pop structures. In a different set of circumstances, perhaps Sideways To New Italy would be a rather different record.

“So I guess [the album] took a bit of a left turn and then came back into line to make more sense,” he reflects. For a body of work so concerned with space and time, there seems to be something pertinent about the notion that the album itself travelled some mileage before reaching its final destination.

Upbeat album opener The Second Of The First heralds a triumphant return, packed with the kind of interwoven guitar hooks that are so quintessential of the band. The chorus beats with the subtle melancholy that Rolling Blackouts pull off so well, captured somewhere between the exchange of harmonised vocal melodies and sinuous guitar lines. The song’s climax comes in the form of a spoken-word bridge, whose voices eventually cross paths intelligibly, reinforcing the surrealism of the experience depicted: “Nothing is the same, the street hasn’t changed/There’s a light feeling in the back of my head/And my mind is somersaulting/I’ve gone out of myself, as if I’m lying in a cloud/And way down there below me is the body I used to have.”

The band have spent the intervening years between the release of their two albums relentlessly touring. Thus, one of the prominent themes of Sideways To New Italy is a feeling of a tug-of-war between places – and the subsequent yearning to find a sense of home that can be transplanted.

These themes prevail in third single Falling Thunder, initially released back in March, a track whose chorus eagerly showcases the band’s melody writing capability. “Is it any wonder/We’re on the outside/Falling like thunder/From the sky,” the band ponder as they reflect on the inevitable passing of time, the eeriness of displacement never far away: “Like a ghost at the service station/In some far off fencepost nation.”

One of the intriguing things about Rolling Blackouts is the fact that the band has three singers – White, Tom Russo, and Fran Keaney – who share songwriting duties between them. I ask White how it comes to be that Rolling Blackouts presents such a unified voice when it is in fact made up of three. He responds by laughing.

“Maybe it’s just lucky. Or the fact that we’ve known each other for, well, forever really,” he resolves. “And we talk about stuff all the time. We talk about songs and songwriting, and what we’re thinking, so maybe that actually does make its way into the songs somehow.”

Despite having a notably consistent voice, each singer has their various agenda. White began writing for Sideways To New Italy with “a lot of post-2019 Australian election kind of angry political songs” which he later decided weren’t very good. Then, somehow he found himself writing love songs instead.

“I realised there’s this great thing that happens in love songs where the darkness comes through – and the sadness, or the heartache, is where the best love songs come from,” he describes. “So I started writing those kinds of songs.”

That ability to capture some underlying, inarticulable melancholy is perhaps what makes Rolling Blackouts so special. On tracks like She’s There and The Only One, notions of love are darkened by the inevitable passing of time.

“Stuck on the edge, she said/Time it’s a river/Only one way, down together,” White describes in the former, amongst long, drawn-out guitar lines that bend against the beat. And later: “All my accidents breathe in time.”

And then on The Only One, the nostalgia of solitude comes through hard and fast: “I found a jewel/Deep end of a swimming pool/I knew what I was lacking/So I threw it back in…Now I drive the ring roads/Sing my songs/Suspended in the air/I could be anywhere.”

When I ask White which songs stand out to him, he praises album closer, The Cool Change, penned by Russo. It’s a song whose narrative in some ways echoes the trajectory of Bob Dylan‘s Positively 4th Street. “It’s this idea of a guy who’s too big for his small town – Melbourne, or whatever – and moves to L.A.,” he tells me. “A big fish in a small pond going over to be a small fish in a big pond, and then coming home and being embraced by love again, or just continually coming home because things don’t go as well as he’d have hoped.”

Perhaps, the song which best combines the intersecting perspectives which form the foundation of the album is Cars In Space. “In my head, this song is set inside a car,” Keaney described of the track upon its release. “It’s the swirling words and thoughts before a break-up.” It’s upon the jangly, upbeat backdrop of Cars In Space that these two notions of love and displacement come to fruition, punctuated by the whip-smart basslines of Joe Russo. “Your face/It shines/In the flicker/Of the film,” the lyrics describe of the ephemerality of love. “You want/It simple/How hard/You make it.”

I ask White about New Italy, the album’s eponymous locale, which has nothing to do with the European country and everything to do with a small town in northern NSW.

“It was just a story,” he tells me. It’s a place they’ve driven by a few times, and near where their drummer Marcel Tussie is from. “It’s just a funny little roadside stop with a museum – and the story really rang true with us.”

The story behind the place, he tells me, is one about immigrants who, jilted by a charlatan, ended up in Australia and built a mock-Venetian town. He’s referring to the ill-fated De Rays Expedition of 1880, where a French nobleman transported three hundred and forty Italian colonists aboard a ship to New Guinea, in the hopes of starting a colony in the South Pacific. The journey was a scam, and one hundred and twenty-three colonists died before the rest were rescued. Many of these survivors took up residence near Woodburn, New South Wales, in an area that was later named New Italy.

For White and the rest of the band who grew up amongst the suburban streets of Melbourne’s Brunswick, there’s a familiarity to the odd anachronism of this Roman-statue-dotted town.

“We spend a lot of our time in Brunswick,” White tells me. “Where we’ve all grown up and we make our music. And that idea of people bringing their heritage with them and creating a sense of home elsewhere, it just sounded really evocative to us. It’s something that might have come from travelling so much and being away, and then coming home and trying to figure out what we would take with us if we were to move somewhere else.

“We just started calling the record New Italy in the very infancy of it because that was the working title, and then it sort of just made sense to call it that in the end.”

Sideways To New Italy is out now, grab your copy here.