Becoming a giant

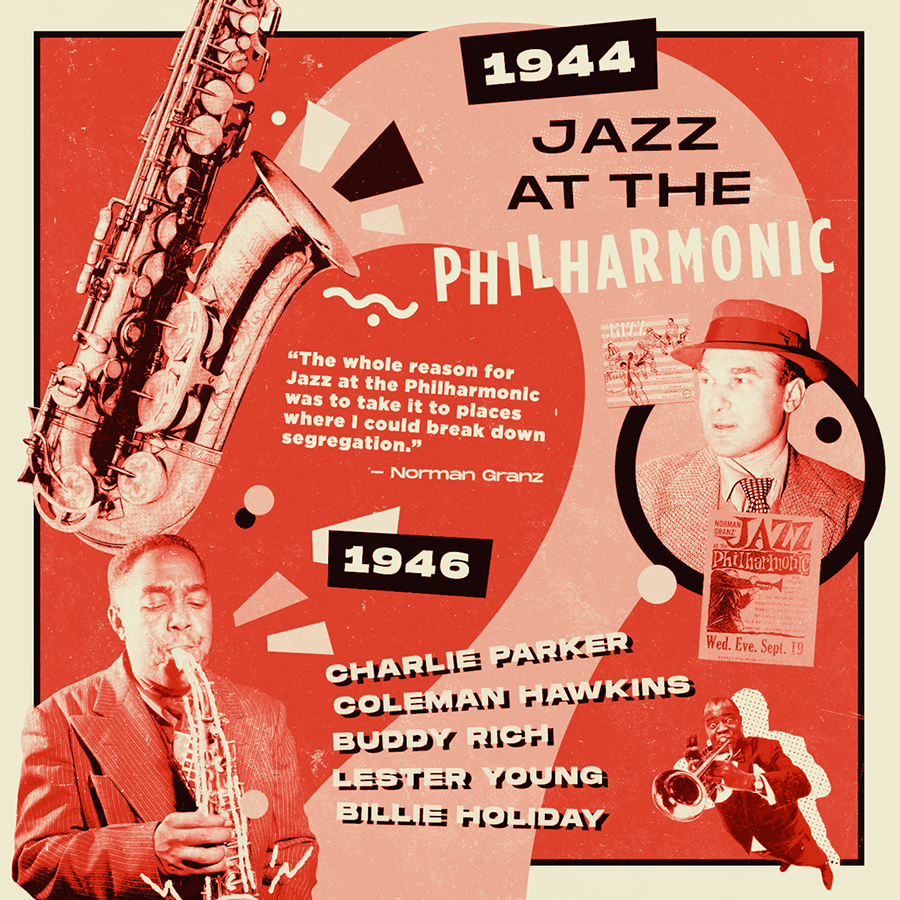

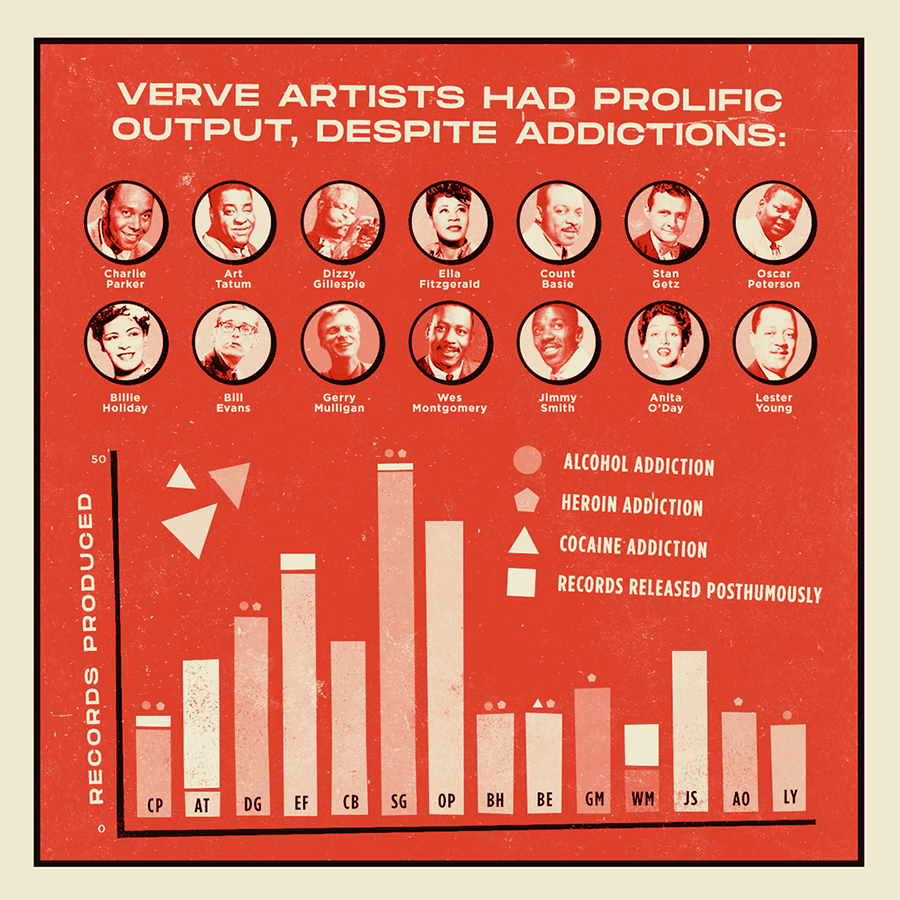

Initially, starting Verve Records was a way for Granz to expand his JATP franchise. Soon enough, artists who were appearing in both the crowd and onstage recognised the opportunity for making studio records with Granz. By the bookend of the 1940s, Granz had already signed some big names to his fledgling Clef and Nogran labels including Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie, Lester Young, Count Basie, and Stan Getz.

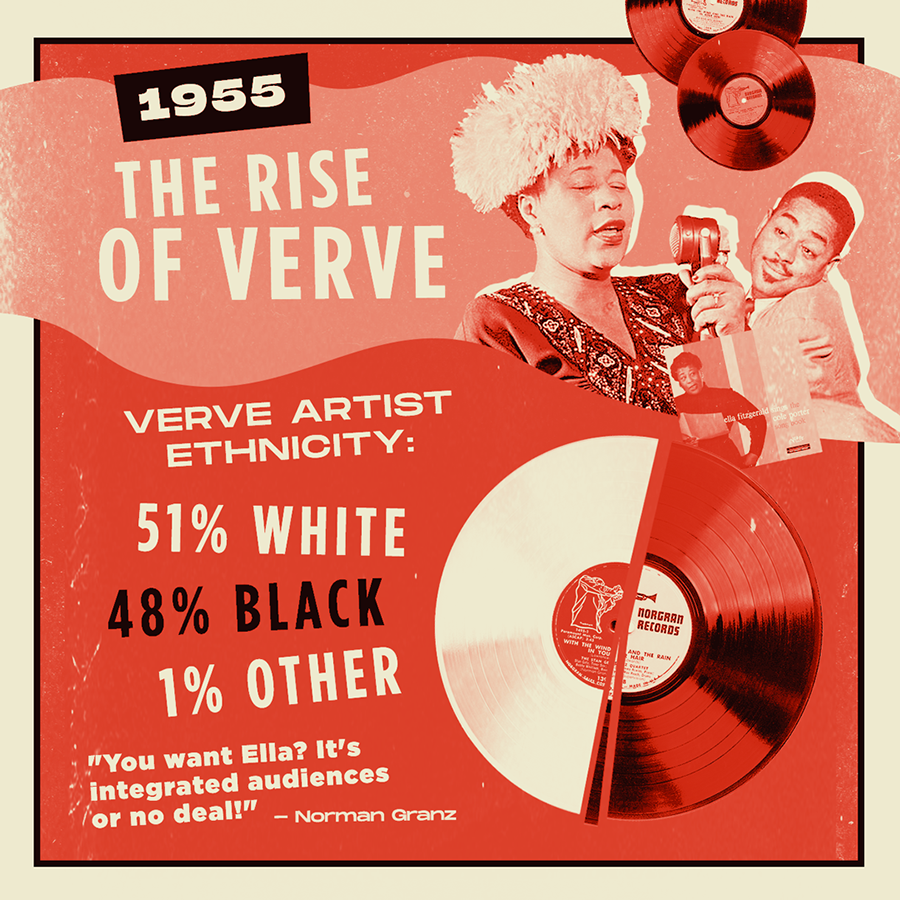

On Christmas ever of 1955, the announcement came that Granz was forming a new conglomerate label. Granz was quick to submerge Clef and Norgran Records under the umbrella of his new parent company. This genius merge gave his embryonic label a roster of notable names and records. This relatively small but potent host now represent what is widely referred to as the golden era of jazz.

So much so that both George Avakian, Columbia’s head of jazz, and his opposite number at RCA Victor, were finding it tough to keep up. Only Blue Note Records, who earlier that year had released Miles Davis’ first 12″ LP, had the independence of mind to operate outside of major labels and garner a roster to rival Verve’s own.

Granz did not rest on his laurels, quickly getting to work by signing new artists with a wider scope in musical proclivity. This, in turn, swung many new fans around to jazz as the blossoming genre began to supersede the backstreets of America’s greatest cities.

Some of the most triumphant recordings from this early period include Ella Fitzgerald’s Great American Songbook, beginning The Cole Porter Songbook in 1956. The crowning jewel, however, was the clairvoyance to permit a duet album with Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong. While not an obvious choice of duet partners, the result was brilliant and came to be known as the one of the most important jazz singing albums in history. Satchmo’s recording with Oscar Peterson – who played piano on aforementioned albums – is another case of plucking two musical giants, pairing them together, and creating magic in the studio.

Peterson, a Canadian pianist, was the second most prolific artist on Verve Records with a total of 47 albums. He was followed by Stan Getz at 43 and Ella Fitzgerald at 42. His work as a fearsome leader of a trio or quartet truly shines with albums like the Great American Songbook, The Jazz Soul of Oscar Peterson, or Oscar Peterson At The Concertgebouw.

In its early years, Clef boasted two of the best jazz pianists alongside Peterson; Art Tatum and Bud Powell. This trio reigned supreme over the keys until 1962, when another expert of the black and whites made his debut record for Verve; Bill Evans with Empathy. This was the pianist that would go on to record Kind Of Blue with Miles Davis in ’59, the most widely revered jazz record in history often described as being“made in heaven”. Evans recorded a total of 16 albums with Verve, expressing the vast diversity of his timbre on albums like Conversations With Myself and the majestic Bill Evans With Symphony Orchestra.

This was the golden age of hard bop, bebop, and indeed jazz in general with some of the most musically and culturally important works of all time being released, many via Verve. As the ’60s dawned and rock and roll generated favour, Verve had to pivot in order to reach a new audience and stay ahead of the curve.