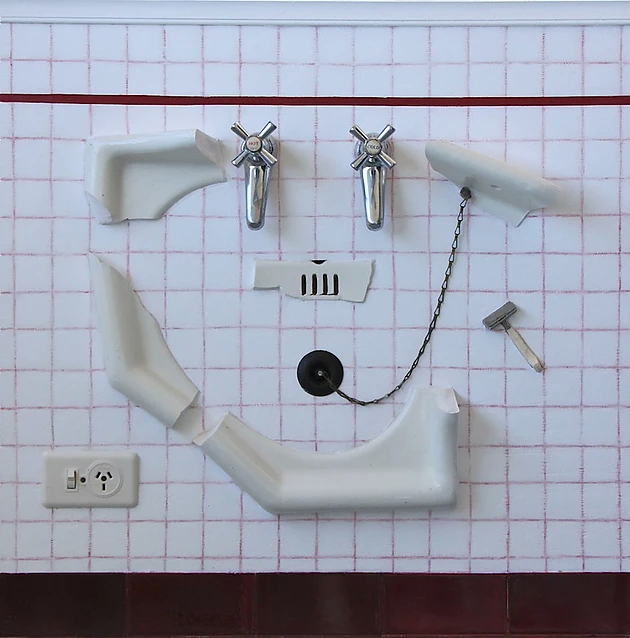

Susan O’Doherty’s latest exhibition Pinned to the Wall is guaranteed to make your head spin and send chills up your spine. Juxtaposing surreal, geometric backdrops and ghostly appendages with run-of-the-mill kitchen utensils, O’Doherty’s series of 3D assemblages invokes an eerie sense of perfection reminiscent of Ira Levin’s The Stepford Wives.

Like Joanna Eberhart, we find ourselves troubled by the impalpable impression that behind this idyllic façade of domesticity lurks a sinister reality.

Ironically, O’Doherty’s collection of household representations opens the door on the issue of domestic violence by conveying its vacant, ‘closed door’ veneer, allowing the viewer to fill in the gaps.

We caught up with the artist to discuss the dark side of the domestic sphere, the nature of time and timelessness, and the rigidity of human behaviour.

Susan O’Doherty uses strewn shoes, broken fragments of furniture and haphazard utensils to expose an unspeakable truth: for many women (and some men), the home poses the greatest threat.

HAPPY: Can you tell us a bit about your exhibition, Pinned to the Wall?

SUSAN: I have spent three years collecting objects making assemblages and paintings relating to the domestic sphere and to themes of violence in the home. Using common motifs and decorative backgrounds to denote wallpapers, carpets, curtains and tablecloths, I have focused on the pressure to present a veneer to the world of the perfect home, juxtaposing that with the dark underbelly of domestic violence. The repeated patterns within the works symbolise repetitive patterns of behaviour. The seeds of this work, in large part, stem from my mother’s troubled childhood. Growing up in the 1930s and 40s, she suffered psychological and physical abuse at the hands of her father. I remember her as always having the cloud of his abuse cast over her.

HAPPY: Do you generally prefer 3D constructions and assemblages to painting?

SUSAN: To me it’s the same approach, but using different materials and mediums. The paintings and the assemblages work side by side as complementary idioms. Acquired 3D objects already have a history and a life imprinted on them. Used and pre-loved, they are silent observers to the environments they have occupied.

HAPPY: There are styles and elements within this body of work that are particularly reminiscent of the 1940s domestic sphere. Was this intentional?

SUSAN: Not really. I deliberately selected each object to convey a message – many of the objects and motifs range in age and are timeless implements. They are fingerprints of the past – cups, plates, bowls, and knives are ubiquitous, and have been around since the beginning of civilisation.

HAPPY: In Greek, nostalgia literally means ‘pain from an old wound,’ whilst others have defined it as a ‘wistful affection’ for a bygone era. How do you perceive the experience of nostalgia?

SUSAN: Though a lot of the objects are from previous decades, I’m not looking backwards or using them for nostalgia’s sake. The items used are signposts. Every object triggers some sort of emotional reaction, whether positive or negative. We may have updated the implements of the modern home but the issues that women face in the everyday remain the same.

HAPPY: Why do you think there is often an implicit association between what is ‘old’ and what is ‘authentic’?

SUSAN: It’s easy to look at the past through the lens of the ‘good old days’ with fond memories often loaded with sentiment. We tend to idolise the past as it is irretrievable. Whether the objects are old or new, however, is irrelevant in this series. My intention is not to retrieve the past but to bring recognisable household objects to tell stories to comment on the issues women face today.

HAPPY: Do you think there is genuine value in looking to the past, or do you believe that history is bound to repeat itself?

SUSAN: It’s really important to look at the past but human behaviour never seems to change. We don’t learn well from the past and make the same mistakes over and over.

HAPPY: Weapons (or potential weapons) are interspersed throughout your artistic displays of kitchen and household spaces. What comment are you trying to make there?

SUSAN: Any object can be used as a weapon given the intention. The home is meant to be a place of safety and yet most murders occur there.

HAPPY: The most unnerving assemblages, for me, were the ones that featured knives alongside other mundane kitchen utensils. Do you think there is something particularly eerie about the dualistic function of a knife as a tool and a weapon?

SUSAN: No, it all depends on the context.

HAPPY: One in six women in Australia have experienced violence at the hands of a partner or former partner, and one in three will experience violence during their lifetimes. Why do you think Australia has been such a hotbed for domestic violence?

SUSAN: I don’t think this is exclusively a local issue. Domestic violence is an issue that women have faced for centuries all over the world. Apart from the physical and psychological violence they face, many women don’t have basic human rights – education, employment, birth control, and freedom of speech.

HAPPY: What can we expect from you in the future? Any projects planned for 2017?

SUSAN: Pinned to the Wall is travelling to Coffs Harbour Regional Art Gallery in March 2017 and will be an expanded version of the Spot81 exhibition. I also have an upcoming dual exhibition with my partner Peter O’ Doherty called Moving House that will feature at the Maitland Regional Art Gallery from February 3 to April 2.

Pinned to the Wall is open now, running through until the 4th of December at Spot81 in Chippendale, Sydney.