In 2015 we live in a music lover’s paradise. There is more music being found, made, discovered and consumed than ever before. To the consumer this music is often for free or if not available for little cost.

With the advent of music streaming listenership has grown in unprecedented ways and numbers, but the money fans are generating is not reaching artists. Low payouts, opaque accounting practices and a number of intermediaries between the artist and streaming services are a concerning reality of the new music marketplace.

With music streaming growing at an exponential rate that is poised to shape the musical landscape, it is alarming to see artists receive underwhelming returns for their work.

The streaming boom

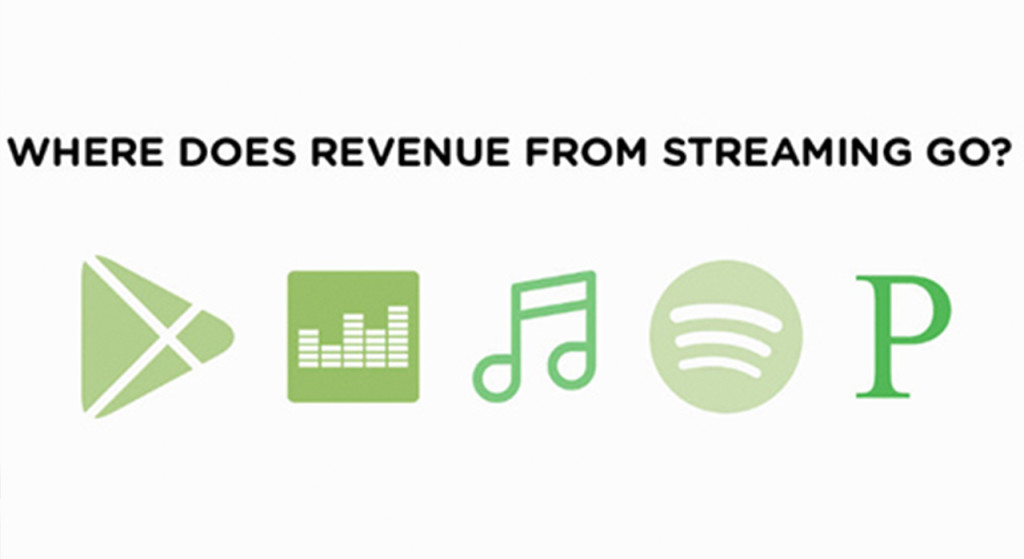

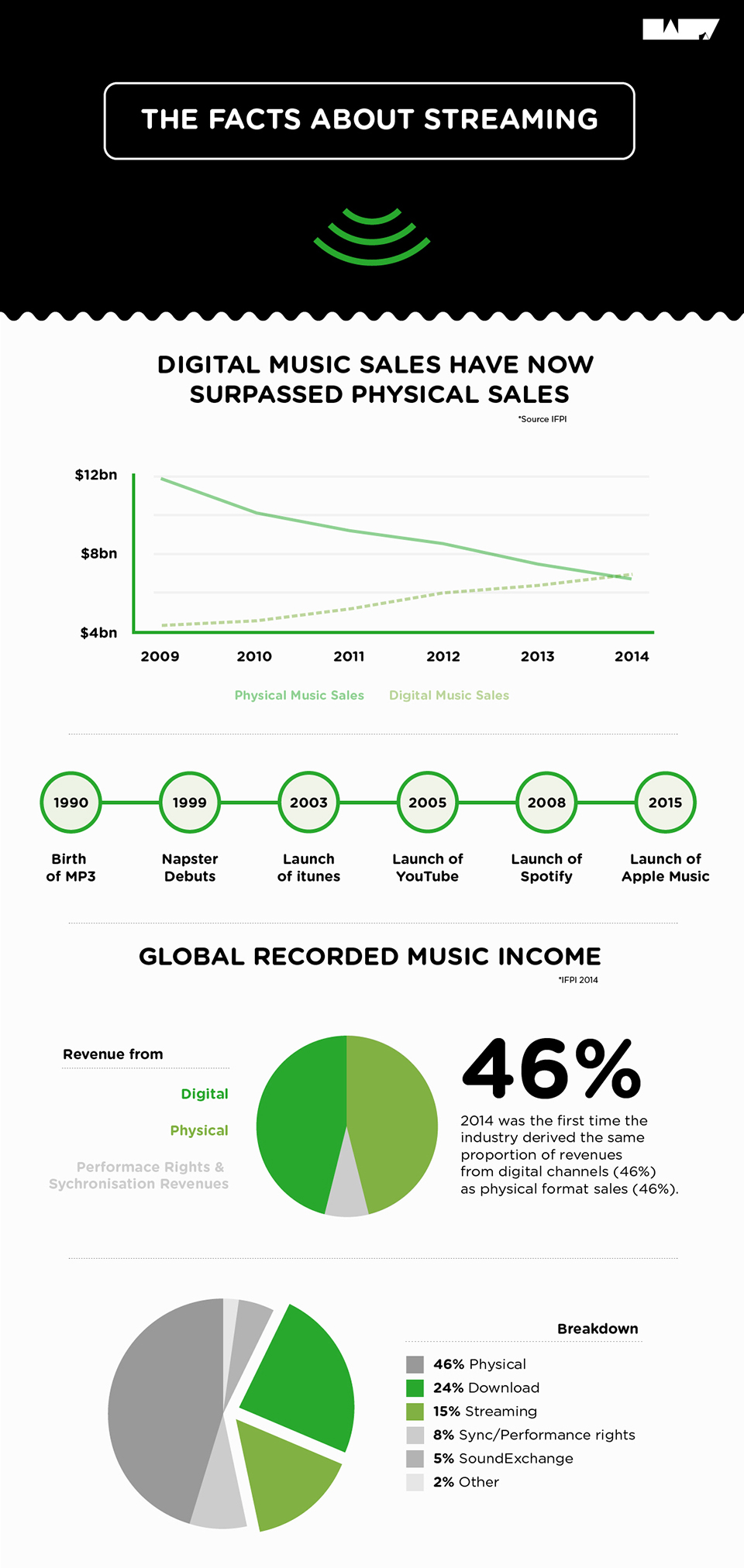

The music industry has been a turbulent place for last 15 years. In the early 2000s the prevalence of illegal downloading as a means of obtaining music sent the industry into a downward spiral from which many thought it could never truly recover. Seemingly coming out of nowhere, streaming services saved the record industry by providing a free, or very inexpensive, alternative to illegal downloading.

In 2015 the market for recorded music looks to be on the rebound and comprises some $25 billion (U.S) of a $45 billion dollar global music industry. With the exception of vinyl, the sales of which account for only around 2% of overall industry revenues, music is rapidly becoming an entirely digital proposition. It is estimated that if music subscription services, which currently reach only a fraction of their potential market, continue to grow at the current rate by 2020 the global music industry will have doubled in size, becoming larger and more lucrative than ever.

How on-demand streaming works

Royalties derived from copyright protection of musical works and sound recordings provide an income stream which is the lifeblood of the music business. Every time music is played on platforms like Spotify, Rdio, Rhapsody, Google Play or Apple Music, money usually a small fraction of a cent, must be paid to those who own the rights to the song.

These royalties are derived from the monetisation of the two forms of copyright protection which attach to songs, the sound recording (the recorded performance) usually owned by labels and the musical work (usually embodied in the lyrics and musical score) typically owned by artists or music publishers. Each form of copyright protection comes with a number of rights which must be licensed by digital streaming services in order for them to made available to the public.

Should artists be receiving a greater cut of streaming revenues?

In 2014 there was a tide of bad publicity concerning the dismally low royalty payouts from streaming services. Pointing the finger at streaming services prominent artists such as Pharell Williams were openly critical of dismally low returns from songs streamed millions of times. Certainly streaming services are not immune to claims of foul play, but what is really going on here?

While blame has often fallen upon streaming services rather than labels, Rethink Music Initiative’s recent paper has questioned this. The report highlighted the issue of why record labels are entitled to disproportionally high cuts of streaming revenue in light of the comparatively small share received by artists. The industry standard is that most online digital platforms (including Spotify, Deezer, Rdio, Beats and Rhapsody) pay 70% of their gross revenues to rights holders (labels, distributors, publishers and aggregators, [YouTube proves to be an exception, doling out only 50%]). This percentage is not abnormal, streaming services are paying the same 70% royalty percentage that iTunes has used for the past 12 years.

Once a label receives money from streaming service it pays artists based on the terms of their recording contract. This rate of payment is usually low. According to a study conducted by Ernst and Young and French trade group SNEP labels examined received a greater share of revenue from streaming services, lining their pockets with 73.1% of the money passed on from streaming services while songwriters and publishers split 16% leaving artists 10.9%. For every $9.99 subscription paid artists received a paltry 68 cents.

As Talking Heads frontman David Byrne noted in his recent opinion piece for the New York Times the recording contracts which determine artists’ payments are designed for the sale of physical products which have low royalty rates, many deductions and recoupment costs for advances. In many cases little or no royalties will reach the artist. Although agreements may vary from artist to artist, the industry standard (a commonly accepted figure is around 12% for new artists in Australia) of revenue from music is paid to anartist.

This is calculated on traditional norms regarding physical products with deductions for things like manufacturing material products, breakage and delivery of goods to retail chains. Where digital music can be reproduced an infinite number of times and delivered instantaneously, the costs are marginal. And yet labels act as if nothing has changed and retain the same amount.

Another key issue is that major labels receive advance payments from streaming services to permit them to use their large catalogues of songs in the first place. It is unclear what happens to these large sums of money. Unlike royalties from streaming these are not passed on to the artist. These catalogue licencing deals are a closely guarded secret. Leaked pages from a confidential agreement between Sony and Spotify revealed that Sony had received a sum of $40 million over three years from Spotify. As this agreement contained a ‘favoured nation’ clause, which provides that no major label will get preferential treatment over the others, these multi-million dollar yearly ‘service payments’ can be assumed to be commonplace. Again this stream of revenue is not being passed on to the artist.

In lieu of money, major labels can also possess equity ownership shares in streaming services often in exchange for licencing their catalogues of millions of songs to be streamed at below-market royalty rates. These sub-market streaming royalties allow streaming services to continue to grow. The potential profits derived from these shares or money made from the sale of ownership. When Beats Music was sold to Apple in 2014 for $3 billion dollars U.S. to be developed into their own streaming service, Universal Music’s parent company Vivendi received $404 million U.S. for their 13% ownership stake.

Despite supporting both the streaming services and labels through deriving low income from their music, the artists receive no compensation. While artists are not benefiting from these arrangements their devalued works are being used by labels as leverage for greater profits.

In most cases independent artists and small indie labels without distributors are unable to directly upload their music to streaming services. Instead they rely upon organisations known as aggregators such as TuneCore and CD Baby who will make music available on streaming services in exchange for a yearly fee or a cut of the royalties. In this sense these organisations act as a substitute for labels by serving as a middle-man between the rights holders and streaming services.

Should artists be entitled to greater transparency in accounting practices for streamed music?

It is not all just about money, but access to information about payments and usage of music. Technology tracks every stream in real-time. Similar to how we access online banking an app or webpage could provide for in-depth and real-time information on royalties from streaming services. Despite the possibilities royalty information still arrives to an artist or their manager in the form of a stack of paper, either too incomprehensible to be useful or lacking in information. This also reflects the reality that many labels and publishers who are passing on this information do not receive data quickly or in an easily decipherable form.

In his opinion article for the New York Times David Byrne expressed frustration at being repeatedly stonewalled by labels and digital streaming services when attempting to ask basic questions about how his share of streaming profits were being calculated. After being rebuked by YouTube when inquiring as to how advertising revenues derived from videos with synchronised music, Byrne contacted Apple to learn how they calculated royalties for their trial period for their Apple Music streaming service.

After contacting Apple he was informed that the company would only talk to copyright owners. Byrne, the owner of the copyright in some of his music and an independent label, turned to his digital distributer with the same question only to be to be informed this information would only be provided if legal teams were involved.

Under the current industry structures it can take months, even years to determine all the rights holders associated with a particular song and send the money down the appropriate channel so it can reach the artists. In many cases royalty payments may not be reaching their rightful owner. There is simply a lack of information about who is owed what money, in 2009 an organisation called Sonicbids partnered with SoundExchange to forensically assist 10,000 artists, mainly indie artists, to recover $4 million U.S. in unpaid royalties.

Rethink Music contends that an estimated 20-30% of payments for playing music do not make their way to rightful owners. The record industry is governed by many unique and frequently confidential legal agreements between artists, record labels and publishers making it difficult for artists to audit their royalties. Without access to data many musicians cannot know that they are owed money or even have a channel through which they can seek this information. If a mistake has been made the artist can never know. This creates little incentive for those holding the money to hand it over.

Should artists have access to data concerning when and where there music is streamed?

Artists should not only receive more information about their payments, but also as much data as possible about their music. When a song is streamed a wealth of information in the form of data surrounding who is listening to an artist’s song is collected. Such information could be useful for a range of reasons, for example knowing who is listening to music where and in what countries can provide artist insight into their fan bases and where to focus marketing or touring their music. While much of this information could be of great benefit to an artist it remains a closely guarded commercial secret.

We live in an age where data is a serious stream of revenue. Business Playlists.net and Hype Machine are built entirely around crunching numbers relating to music discovery and consumption. Other ventures like NextBigsound (recently acquired by streaming service Pandora) offer artists access to certain data on streaming for payment. Considering the value of data analytics as another revenue stream there is certainly some reluctance on the part of streaming services and labels to provide unrestricted access to raw data for free. A counterpoint is that surely artists should have some entitlements to certain information about their music and that allowing artists access to information (on a confidential basis) could further the collective benefits of all parties involved.

Is there a need for greater awareness?

A key issue which cannot be overlooked is that many musicians are simply unaware of the rights they have as creators. A greater number still are in the dark about the payment structures through which their royalties, a key source of their income, are derived. The burden does not just fall upon streaming services and labels, there is broader need for those within the musical community to foster and promote a better understanding of these rights and the issues effecting artists.

Conclusion

Streaming services are growing at tremendous rate, yet large pools of revenue remain outside of the reach of artists. Rethink Music and David Byrne have actively denounced the current industry structure as a complex and out-dated model from a bygone era of discs and tapes which hampers the flow of information and equitable compensation to musicians. While they level accusations that labels and streaming services fight to preserve the lucrative pre-internet industry structures, they also contend that a better royalty and data infrastructure does not solely benefit the artists, but also the music industry as a collective whole. The interests of artists and other industry bodies may not always align.

This said when it comes to streaming the fact remains that in many respects artists, labels and streaming services are business partners with common interests The Rethink Music Initiative have gone as far to demand an Artists Bill of Rights, a series of industry standards providing for fair compensation which includes:

- a right to know where and when their music is performed,

- up to date reporting of use of their works (within 30 days for online),

- a right for creators to be digitally identified as the owner of their works,

- a right to know which parties are taking cuts of revenue from streaming before it reaches their hands, and

- the right to set the value of their work at a fair market value.

It stands to reason that the artists and writers who create the content which drives streaming services should be afforded transparency and fair remuneration for their music, but should artists be entitled to the better part of that 70% that’s being payed onwards to labels? Should they be entitled to an equal share of the revenue major labels are making from clandestine equity and catalogue licensing deals Should streaming services be forking over all of their raw data? Do intermediaries like aggregators need to exist at all?

These are all extreme propositions. In many cases these organisations have an integral part to play in the commercial processes which allows many artists to make a living from their music. Before these issues can be resolved there is a real need to open the debate as to reach a greater consensus as to what rights like those proposed by Rethink Music might actually entail. But before these discussions can commence there is a need for more information and more communication. Artists need to know what is going on.

Check out our article on how to promote your band with Australia’s top publicists here too.

While you’re here, have your mind blown by these song facts about classic tracks.