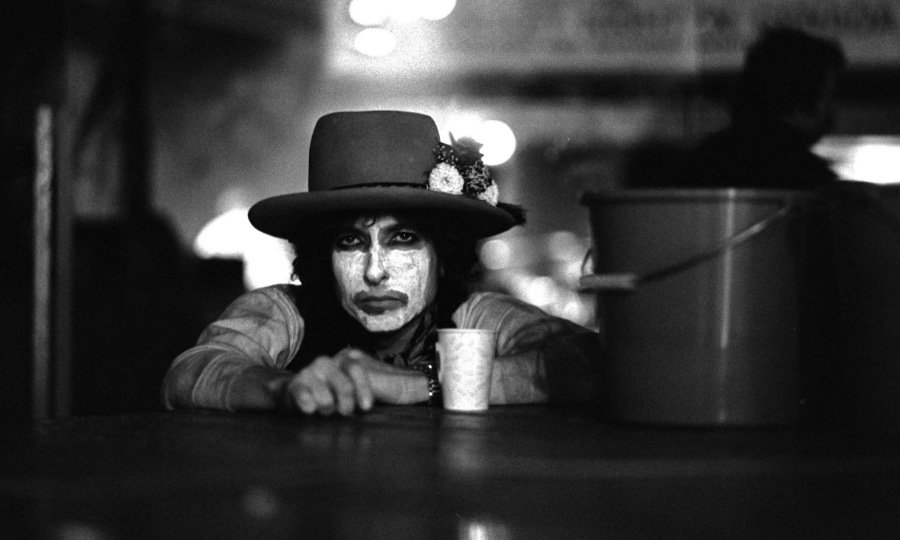

Is Bob Dylan the last surviving troubadour? A brief history of the travelling song men of the High Middle Ages before the Black Death wiped them out.

Bob Dylan was a troubadour. Or so they say. The romantic vision of a minstrel drifting from town to town with only a guitar, a sack of pennies, and a voice remains a burning focus of academia, art, and the Folk Renaissance of the 1960s. Though folk was always a rather romantic genre.

But how did the occupation of itinerant Medieval musicians become synonymous with a sporadic decade of folk music, and more specifically Bob Dylan? From the High Middle Ages to the 1960s, this is the story of the troubadour.

Who were the troubadours?

The major contrast with the modern romantic conception of troubadours is that they were not wandering, wayfaring musicians. They generally remained with a wealthy patron travelling from court to ebullient court.

The High Middle Ages were a time of robust economic and population growth in Europe commencing around 1000 a.d. and ending roughly at the 13th Century. It was preceded by the Dark Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages – noted for its calamities such as the Black Death. Nevertheless, they had it good for a few hundred years of cultural opulence.

The Renaissance of the 12th Century was a particularly high moment of the era. Knights became increasingly common as a rise in chivalry led to tournaments being invented as a way for serfs to earn their freedom. The Crusades also occurred between the 11th and 13th Century as a way to establish Christian rule in the ‘Holy Land’.

More than ever monastic militants prevailed and Christian rule dominated. Interestingly, troubadours became well known secular entertainers, moving beyond religious themes to explore love and politics. This is perhaps where the troubadours of the 1960s got their inspiration, railing against dominant power structures of their time.

The first troubadour with surviving work is Guilhem de Peiteus who lived between 1071-1126. A key part of the troubadours identity was that they performed their own original material, though some troubadours, such as Arnaut de Maruelh, employed additional musicians such as ‘jongluers’ to perform their work. This was not typical, drifting more towards minstrels, who recited poems or songs to accompaniment. A bard, on the other hand, would recite or write heroic or epic poetry without music and were often of Celtic origin.

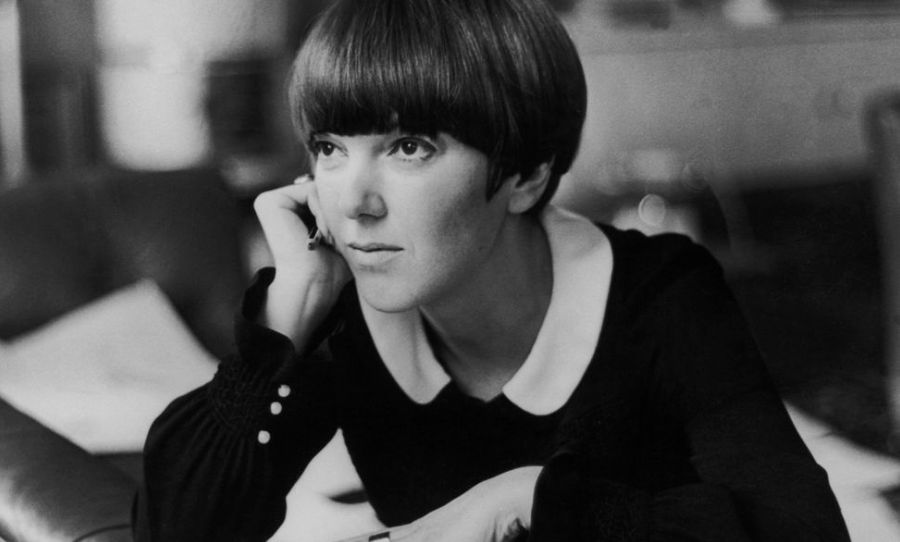

While Medieval society was brutishly male dominated, there are instances wherein women rose to prominence. Female troubadours were known as ‘trobairitz’, as troubadour was typically a masculine word. While they were less surviving manuscripts demonstrate

Musical and poetic similarities

Troubadours composed their own music and coupled this with original lyrics, demonstrating their immense capability as musicians. Much like the folk artists of the 1960s their sheer originality saw them embraced by the era.

The most common instruments in the High Middle Ages were woodwind and stringed instruments. Woodwinds such as the pan flute or recorder were often used for accompaniment but were rarely the primary instrument of the troubadour.

Instead they opted for strings to that they could sing and play. Lutes, gitterns, psalteries, rebecs, or citherns were commonplace for troubadours. Again this simple arrangement mirrors the ideals of folk purists.

The most popular forms of troubadour song craft still survive to this day. The sonnet and the aubade, of which Bob Dylan wrote many – Tangled Up In Blue and One Too Many Mornings. A tenso is a particularly interesting genre which is sung as a two-voiced debate – Boots Of Spanish Leather.

Finally, the majority of musical compositions for troubadours were monophonic, meaning they sung one note at a time without harmonies. Monophonic compositions relate to the chanting music used in churches in the Early Middle Ages and were rather simple in nature.

Again this is a conviction of the folk purists. Just one voice and the golden strings.

The modern troubadour

While there are many ‘troubadours’ that defined the 1960s, none defined the culture quite like Bob Dylan. He has been called everything from a ‘broken leg dog’ to the embodiment of Ovid, but more than anything he personified the freewheeling ways of the troubadour.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), The Times They Are A Changin’ (1964), and Bringing It All Back Home (1965) are widely recognised as folk masterpieces, carrying on the tradition of the troubadour into a distinctly modern context. Renowned Harvard Professor Richard F Thomas even published a book in 2017, Why Bob Dylan Matters, arguing a convincing case for why Dylan is a distant poetic relative of Virgil, Ovid, and Homer, continuing the stream of groundbreaking word play.

But Dylan isn’t just the supreme American troubadour. He has tried his hand at prose too. Chronicles: Volume One proved his efficacy for long form profundity crossed with great American storytelling, landing him somewhere between Kerouac and Whitman. And if Chronicles proved it, the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature cemented it.

Overall the essential mystery at the heart of Dylan is that nobody can explain him, least of all Dylan himself. Joan Baez once said, “If you’re interested, [Bob] goes way, way deep.”

Like all great folk artists he defies transcription, and eludes literary elucidation. He is either singularly reflective or murky as a swamp, and like all great mirrors of society, he says what we always thought but couldn’t say. As we listen now, and in the past, and perhaps for centuries to come the sonorous truth of one line will resound: The times they are a changing.