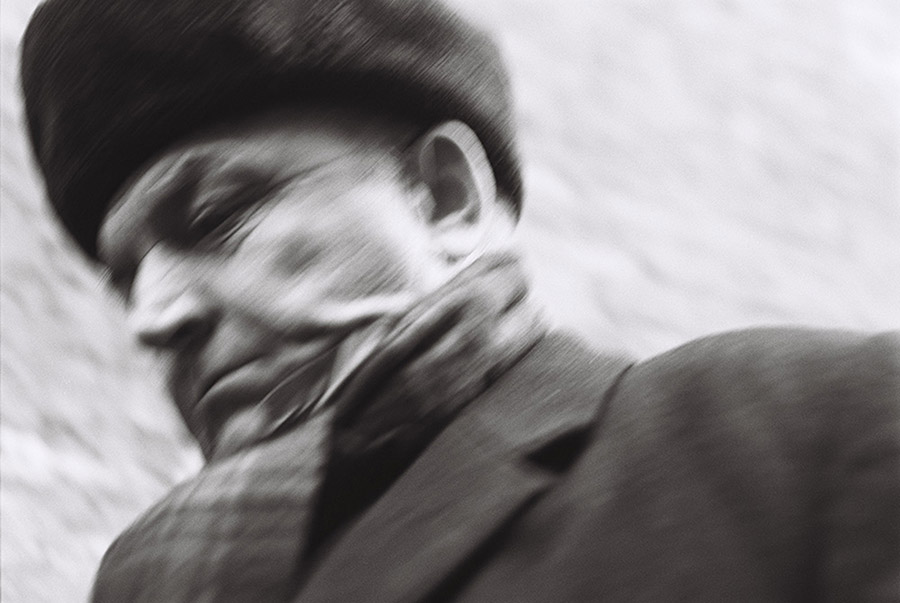

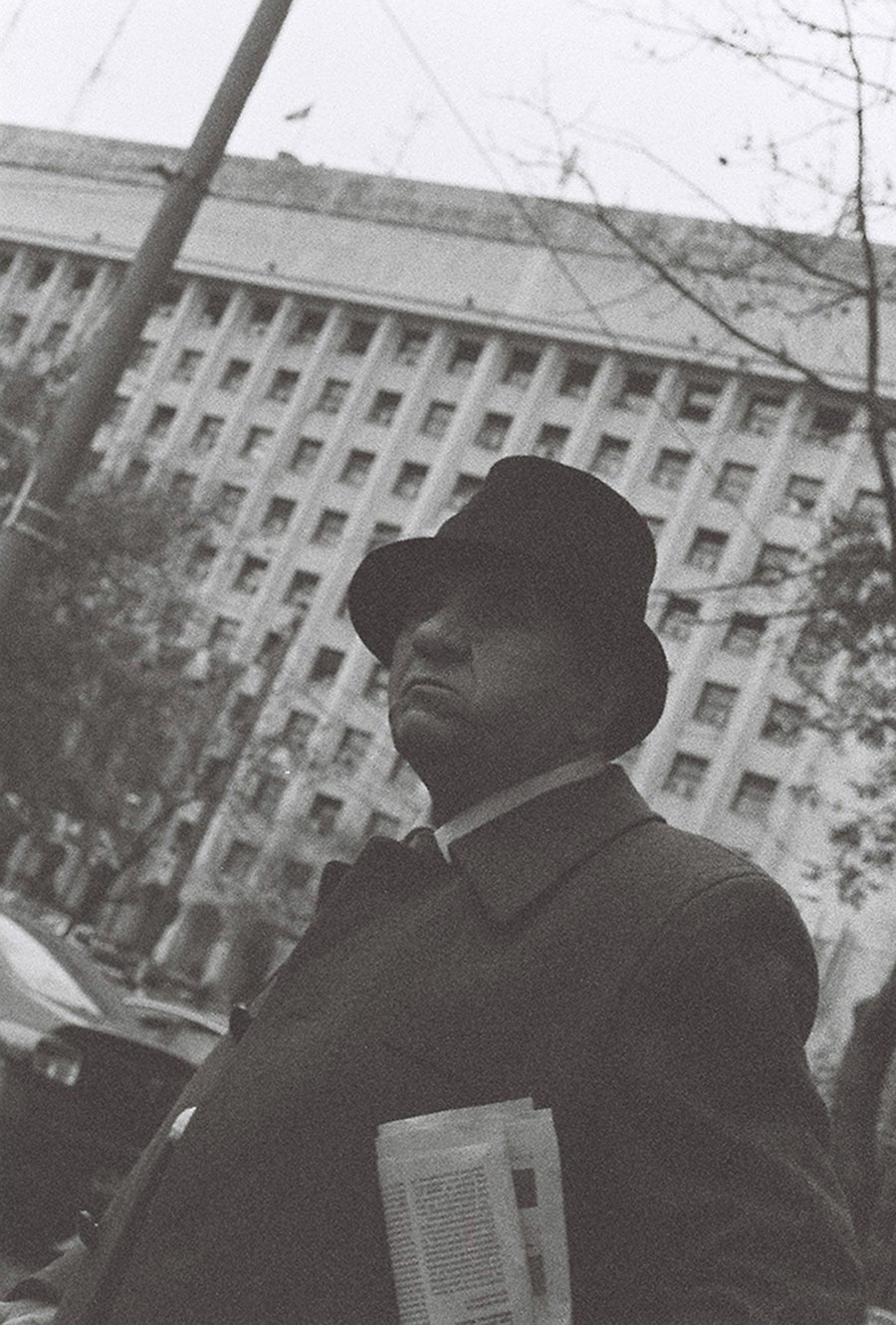

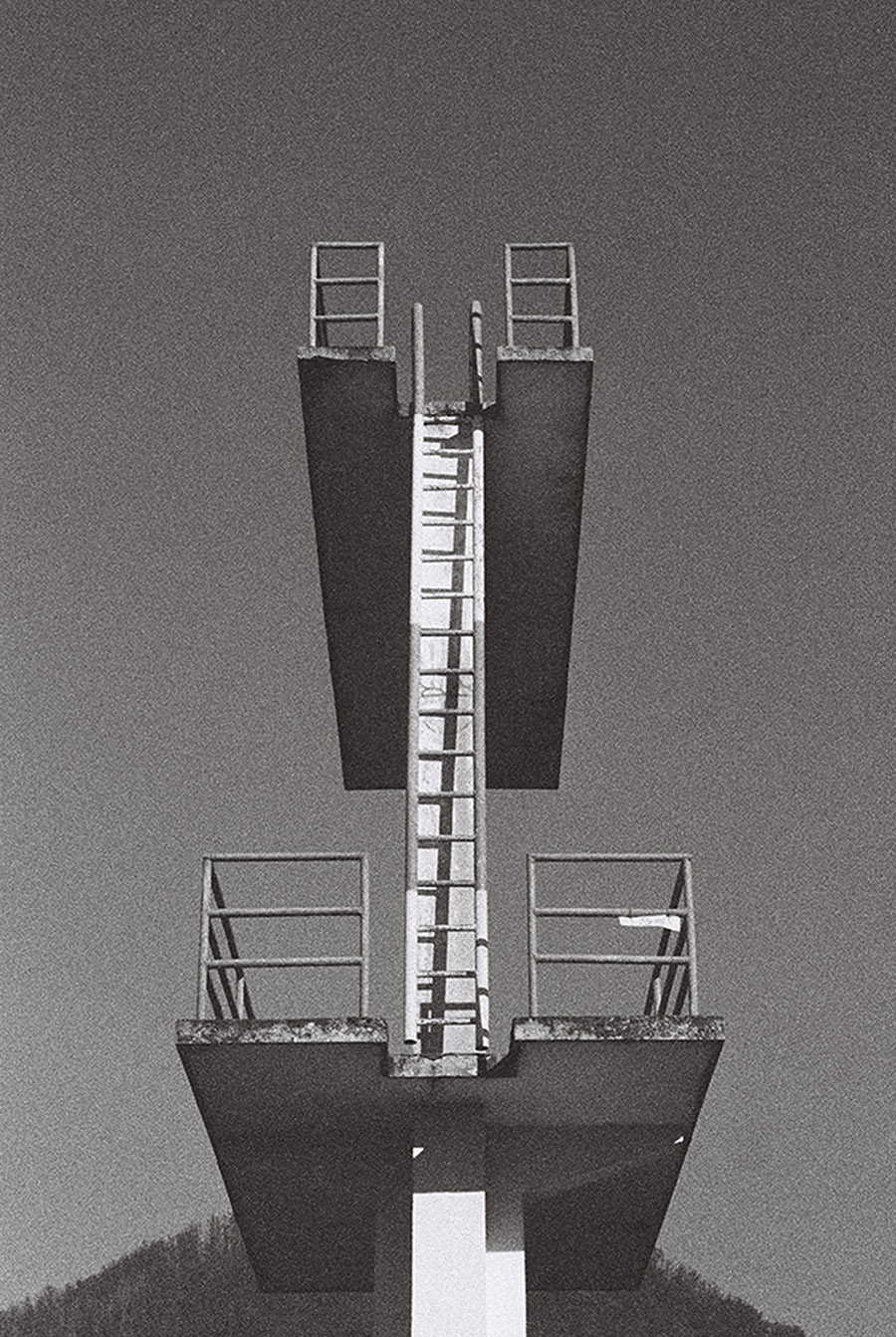

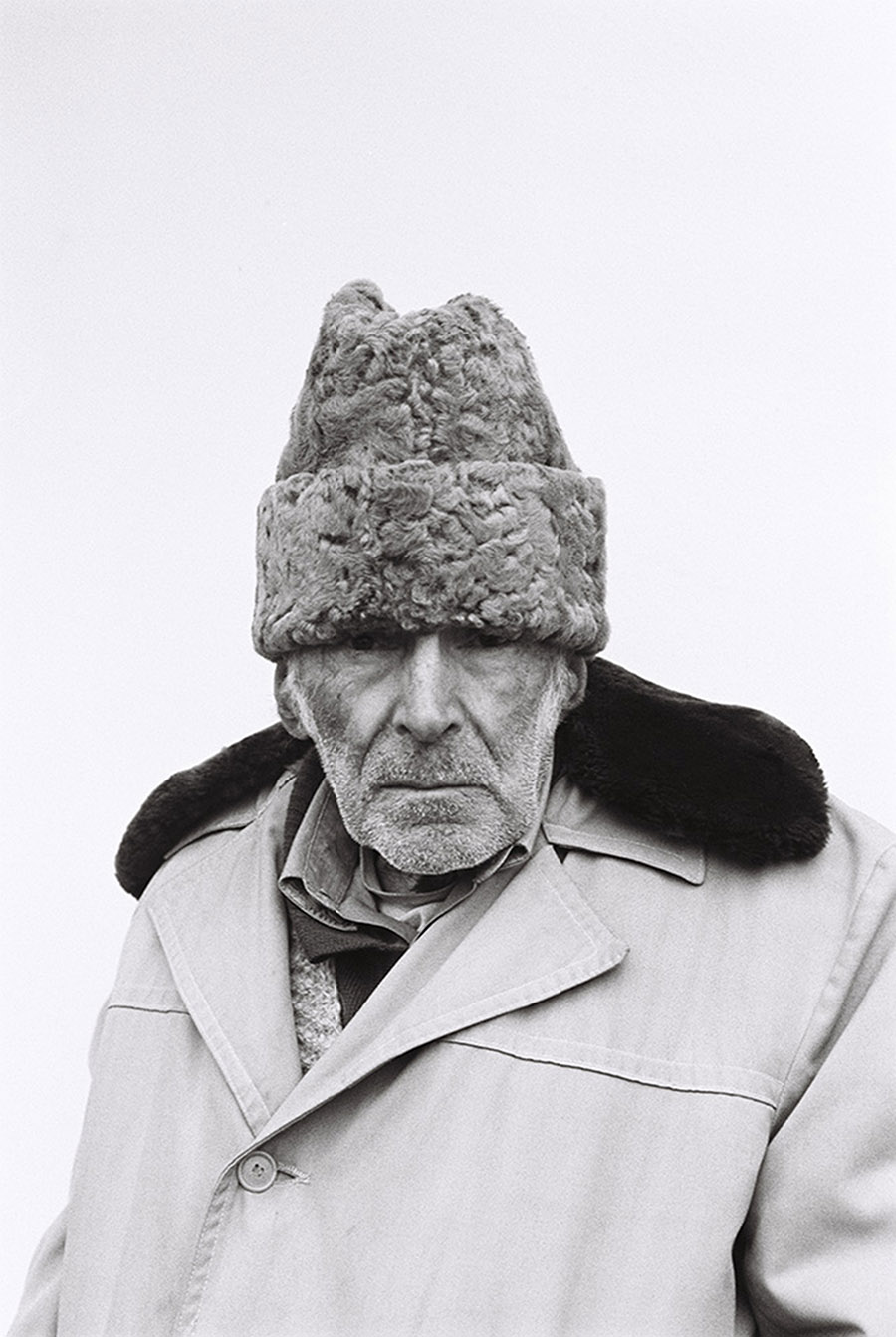

Callum Royle is a multidisciplinary film photographer and graphic artist who divides his artistic drive across multiple projects of highly contrasting tone. These artistic outlets range from the psychedelic collage of PEA + HAM to the stark photographic political portraits of A Sobered Communist and more.

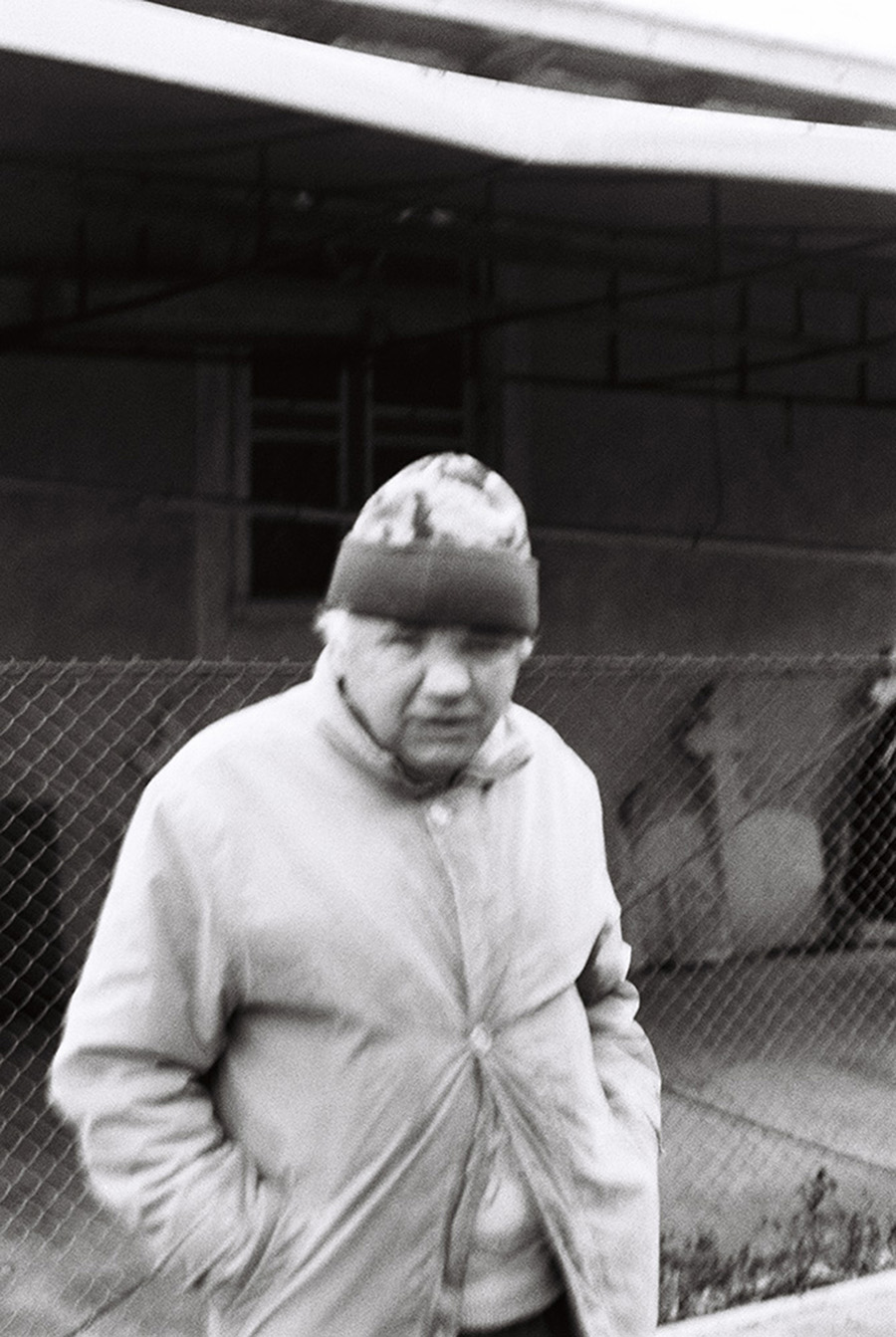

We caught up with Callum to discuss his methodology for his most recent project, A Sobered Communist, which takes an uncompromising look at the aftermath of communism in Romania. Callum’s work returns us to the subversive nature of art in an attempt at representing that which has gone unrepresented by history.

Having faced years beneath a government dictated media, Callum Royle brings to light the psychological character of Romania’s proletariat in the aftermath of a highly traumatic period.

HAPPY: There must be a story behind how you came to take this topic as the centre of your collection, could you fill us in?

CALLUM: To begin with, I was fascinated by the footage of the 1989 Revolution in Romania, and the eventual fall of communism after 42 years. There is so much footage on Youtube showing the violent civil unrest, which saw the execution of longtime communist leader Nicolae Ceaușescu and the loss of thousands of civilian lives. I also watched a lot of documentaries about the orphan crisis.

It is estimated that at the fall of Ceaușescu’s rule some 170,000 orphans were found crammed into 700 overcrowded state-run orphanages, a generation of children raised without care, social interaction, stimulation or psychological comfort. Many of these orphans were direct results of policies banning abortions, restricting divorce and the use of gynaecologists to police women in the workplace.

HAPPY: How did Paul Neuburg’s book affect you personally?

CALLUM: I think why Paul Neuburg’s book The Hero’s Children: The Post-War Generation in Eastern Europe had such lasting impact on me is how it’s written. For about the first 300 pages, you’re are given an in depth historical, social, economical and political lesson on Eastern Europe post war.

Paul does this in anticipation for a series of interviews that he holds with two varying generations. So you get this really beautiful demonstration of the cultural and social gap that divides parents and their children. I should also mention that he holds these interviews over a time period of about 40 years.

HAPPY: How did you approach this topic? Did you actually go to Romania?

CALLUM: Yep! I went to Romania for two months and stayed with couch-surfers a lot of the time. For me this step was pivotal. I always try to stay with people from the country I am visiting as opposed to hotels. It allows me to engage with locals and to understand the culture better. It can be a delicate discussion when you’re asking individuals about their political history so if you can engage with people in a space they feel comfortable you are more likely to get the response you are looking for.

I think as a photographer the last thing you want to do is ostracise yourself from the people you are trying to photograph, so it is really important to understand what makes them tick. One of the things I noticed, is that the men were very touchy feely. So to assimilate, I found myself rubbing a lot of arms and shoulders when talking to strangers! It can be quite funny the lengths you go to to get a good photo.

HAPPY: You refer to yourself as a multi-disciplinary artist. What are the benefits of expressing an idea or project in multiple mediums?

CALLUM: I begin my creative career as a collage artist and graphic artist under the name PEA + HAM. I did a heap of exhibitions and design work under this alias, and found it to be really enjoyable. What I love about PEA + HAM is that if I want to explore a tripped out fantastical world where an Egyptian mummy is squirting blue fire from his eyes or a ram headed martial arts master is fly kicking an astronaut (Lovesick Priest series), I can.

Whereas, if I’m feeling socially inquisitive and globally intrigued, I’ll often research an area of the world, find a topic that I feel needs to be represented, then try to save some money to complete the photography series.

HAPPY: Why did you take a multi-media approach to this project? Did you find that photography couldn’t reach the level of expression you could reach through videography?

CALLUM: Moving image is unstoppable. Personally, I know that if I go anywhere, if I see a TV playing anything, even advertisements, I’m hooked. I think moving image is still so fascinating to us. We interact very differently with the two mediums. With the moving image, you are locked in to a linear narrative – yes, the plot may not be linear – but you watch to find out more about the story. With photography, you read the image subjectively and can dictate the narrative of the image.

HAPPY: Has photography always been a passion?

CALLUM: Yeah, sort of. When I was in primary school, the father of a friend of mine was a photographer for Lonely Planet. So it was definitely something I wanted to do for a while, I then became more interested in design and collage, and even fell down the pipe of wanting to do architecture or aerospace engineering because of money. But I’m glad to see I found my way back to photography.

HAPPY: Is the aftershock from a communist period something that ever fades into total recession? Are we ever really ‘post’?

CALLUM: I think it will have a very lasting effect on the country and the psyche of the proletariat. I think it is a part of their culture and history, and it will be apart of their identities for a long time to come. However, I will bring it back to Neuburg and a fantastic passage where he recounts the writings of an 18-year-old school boy:

“We, the young people, are the owners of the present… the old times are passing into history, and you’ll do us a favour by not reminding us of them, over and over again. You do nothing but lose our confidence.”

There is a pattern of contrast that lies between generations that is most intriguing. It reflects the contrasting histories, amidst which they have grown to consciousness.

HAPPY: Who are some artists you’ve taken influence from?

CALLUM: Robert Frank, Bruce Gilden, Walker Evans, Don McCullin, Eugene W Smith, William Eggleston, Helen Levitt, William Klein, Trent Parke, Nathan Miller, Lee Friedlander, Joel Meyerowitz, Daidō Moriyama, Robert Doisneau, Eugène Atget, August Sander, Melissa Catanese, Martin Parr, Alec Soth, Roger Mayne, Robert Capa, Todd Hido, Alex Webb… in no order.

HAPPY: What does the use of monochrome achieve in this project?

CALLUM: I was there in winter… Eastern Europe is cold in winter… it’s grey and most appears monochrome. It made sense to reflect this!

HAPPY: A Sobered Communist seeks to represent the unrepresented, providing a more complete – albeit shocking – image of communist realities. In such a context art-making becomes deeply subversive. What are your thoughts on the fragile, yet emphatic power of art within anti-democratic systems of power?

CALLUM: “Every culture develops some kind of art as surely as it develops language. Some primitive cultures have no real mythology or religion, but all have some art… The ancient ubiquitous character of art contrasts sharply with the prevalent idea that art is a luxury product of civilisation, a cultural frill, a piece of social veneer.”

“It fits better with the conviction held by most artists, that art is the epitome of human life, the truest record of insights and feelings, that the strongest military or economic society without art is poor in comparison with the most primitive tribe of savage painters, dancers, or idol-carvers. Where every society has really achieved culture, it has begotten art, not late in its career, but at the very inception of it.”

“Art is, indeed, the spearhead of human development, social and individual. The vulgarisation of art is the surest symptom of ethnic decline. The growth of a new style always bespeaks a young and vigorous mind, whether collectively or single. What sort of thing is art, that it should play such a leading role inhuman development?”

“It is not an intellectual pursuit, but is necessary to intellectual life; it is not religion, but grows up with religion, serves it and in large measure determines it (as Herodotus said, “Homer made the gods,” and surely the Egyptians deities grew under the chisels of sculptors in strangely solemn forms).”

“We cannot enter here on a long discussion of what has been claimed before as the essence of art, the true nature of art, or its defining functions; in a single lecture dealing with one aspect of art, namely its cultural influence, I can only give you by the way of preamble my own definition of art, with categorical brevity.”

“That does not mean that I set up this definition in a categorical spirit, but only that we have no time to debate it, so you are asked to accept it as an assumption underlying these reflections. Art, in the sense here intended – that is, the generic term subsuming painting, sculpture, architecture, music, dance, literature and drama – maybe defined as the practice of creating perceptible forms expressive of human feeling.”

“I say “perceptible” rather than “sensuous” forms because some works of art are given to imagination rather than to the outward senses. A novel, for instance, usually is read silently with the eye, but it is not made for vision, asa painting is; and though sound plays a vital part in poetry, words even in poetry are not essentially sonorous structures like music. Dances require to be seen, but its appeal is to deeper centres of sensation.”

Words by Susanne Langer.

Find more of Callum’s work on his website.