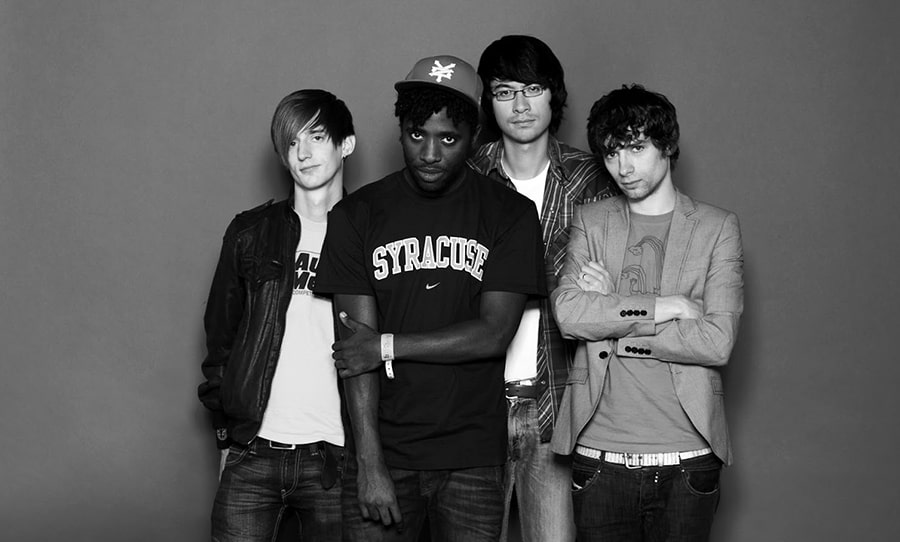

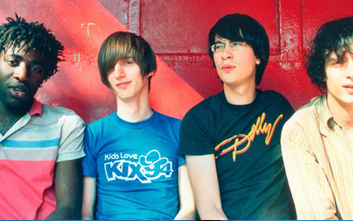

Officially formed in 2003, (only two years before the release of Silent Alarm), Bloc Party originally consisted of singer and rhythm guitarist Kele Okereke, lead guitarist Russell Lissack and bassist Gordon Moakes, with drummer Matt Tong joining soon after auditioning for the band.

After releasing a self-titled EP in 2004 and increasing exposure in the UK music press, Bloc Party found themselves in the unusual position of turning down a recording contract from Parlophone. Instead, the four-piece opted to sign with Wichita Recordings, due to label reputation for not interfering in the recording process. A move that, in retrospect, helped produce one of the best and most influential albums of the noughties indie/post-punk revival wave.

A collision of explosive drums, duelling guitars and rumbling bass lines set under an arena-rock scope – we explore the sleek sound of Bloc Party’s debut album, Silent Alarm.

An Amalgamation Of Genres

The four members of Bloc Party, along with record producer Paul Epworth, convened for just over three weeks at the Deltalab Studios in Copenhagen to record the majority of Silent Alarm (most of the vocals were done in London). Though the band already had demos ready to record, they were more than willing to let Epworth meticulously dissect and re-imagine what they’d written. As such, fifteen songs were recorded during the twenty-two day residency at the Danish studio, with thirteen going on the final product.

Instead of honing in on one particular core sound and sticking to it for the album’s entirety – one of the few befalling factors of indie contemporaries like The Strokes’ Is This It and Interpols’ Turn on the Bright Lights – Bloc Party sought to explore more disparate sonic territories. Working closely with Epworth, the band wanted to create an album that separated them from their contemporaries, dabbling in R&B and dance-punk sensibilities, while still remaining true to their indie rock roots.

During a 2005 interview with Now Magazine, Okereke said of his vision for the album: “I knew before going into the studio that I wanted the album to sound very rich and full – not too flat, like many of the guitar rock records that have been coming out of Britain. The goal was simply to give the music more depth, sonically speaking.”

And depth they achieved. From the frantic stab of Helicopter to the hued ethereality of Blue Light to the crushing apathy of Plans, the album covers a vast expanse of emotional terrain. And ultimately it leaves you reeling – perhaps a little drained, but incredibly satisfied.

Finding the Musical Glue

As per Bloc Party’s outlined vision, Epworth had to find a way to mould the thirteen tracks in a way that they all felt unique from one another, but were uniform in some respect. Epworth ended up finding his uniting element in Gordon Moakes and his Fender Precision Bass.

Placing a large emphasis on Moakes chugging style, Epworth saw the bass guitar as key to creating a homogeneous album. This is most on display in the brawling, punk-tinged Luno and epic brooder, Positive Tension. Even in tracks where the bass takes on a supporting role, such as in Helicopter and Banquet, the growling low-end of Moakes’ bass is planted firmly and distinctly in the mix, providing a unfaltering base for other elements to spring forth from.

Frenetic Percussion

Another key unifying factor found between the songs on Silent Alarm is the booming beats from Matt Tong.

Even before releasing their debut, Bloc Party knew that Tong’s intense drumming style would help separate them from similar artists. So, much like the bass, Silent Alarm’s production placed a great deal of emphasis on the drums – a production trait that Epworth is well known for.

When it came to recording the drums, Epworth used both ribbons and condensers (plus an Electro‑voice) RE20 on Tong’s Pearl kit to achieve the sonorous tone found throughout the album. He also worked tirelessly tuning every drum until he found the ideal tone for each song.

In a 2009 interview with Sound On Sound, Epworth said of his treatment of the drums: “I try not to gaffer-tape drums at all, but I spend hours meticulously tuning them. Sometimes you tune drums and they sound great in the room, and you put mics on them and they sound shit. So it’s a case of tune it, have a listen, tune it, have a listen.”

Right from the opening moments of Like Eating Glass, Tong’s restless style drives the album forth with a manic frenzy. This trait is an album staple, from the sweeping crescendo of Blue Light to the cataclysmic display on The Pioneers. In fact, the only time the drums take a more subdued role is on sombre album closer, Compliments.

Experimental Guitars

Both Lissack and Okereke use Fender Telecasters, plugged into Fender Deluxe amps to achieve their clanging clean tones. But much of the album’s conception in Deltalabs saw the duo experiment with various pedals and pick-ups to achieve those chiming tones. It wasn’t until later on in the recording process that Lissack and Okereke dabbled with distortion pedals.

While Okereke’s rhythm style was a lot more conventional, favouring clean chords with the occasional addition of a Boss DF-2 Super Feedbacker and Distortion for some grit, Lissack ventured down more experimental territories with effects. Often he would use unconventional pedal combinations to come up with new sounds and ideas – ranging from delayed harmonics (The Pioneers) and shimmering broken leads (So Here We Are), to swirling phasers (Plans) and scattering synth tones (Price Of Gasoline).

One of Lissack’s most favoured pedals throughout Silent Alarm is the Boss DD-5, dialled in with super fast repeats. Though making an appearance on multiple tracks, the BOSS classic is perhaps best put to use on the album opener Like Eating Glass.

The track kicks of with a haunting solitary guitar processed through a reverse delay from the DD-5, which is then looped by a DD-6, set to infinite repeats. As the drums enter and the track builds, Lissack manipulates certain parameters of the DD-5 to attain the descending siren sound. Magic.

Passionate Vocals and Maturity Beyond Their Years

Contrasting the seductive crooning of The Strokes’ Julian Casablancas and the laid-back delivery of Franz Ferdinand’s Alex Kapranos, Kele Okereke’s vocals throughout the album are sung with a strong sense of urgency. From the opening yelps in Like Eating Glass to the uplifting climax of So Here We Are – even in Compliments, Silent Alarm’s closer and the album’s slowest track – Okereke’s vocals drip with emotional weight.

The lyrical content varies from song to song without a central theme, but for the most part, the album deals with the responsibilities that come with being a young adult in the 21st century. Tracks such as Price of Gasoline take a more political route, shining light on the Iraq War, while She’s Hearing Voices delves into the heartache of having a friend with mental illness.

A personal lyrical highlight is This Modern Love, examining the early stages of falling in love with clever vocal panning accentuating the conversational nature of the lyrics.

By the time Silent Alarm was released in February 2005, indie rock was beginning taking a dive in popularity. The Strokes and Franz Ferdinand had each passed their respective peaks, The Libertines were well and truly dissolved, and Brooklyn-based LCD Soundsystem were pushed the genre towards more electronic territories.

But Bloc Party’s debut breathed fresh life into the landscape. It did away with the rudimentary drum beats, razor-sharp guitars and pedestrian basslines the genre had become embroiled in in favour of something inspired and spliced together with unrivalled energy, set under the sheen of a seasoned stadium-rock outfit. And in the end, Silent Alarm was an album both ahead of the game, and far beyond their years.