How does one encapsulate a life in music? How does one even contemplate saying goodbye at the end of it all? Perhaps you do what you do best: confound expectations and ceaselessly and bravely experiment, even in the face of mortality. Such was the journey of Blackstar.

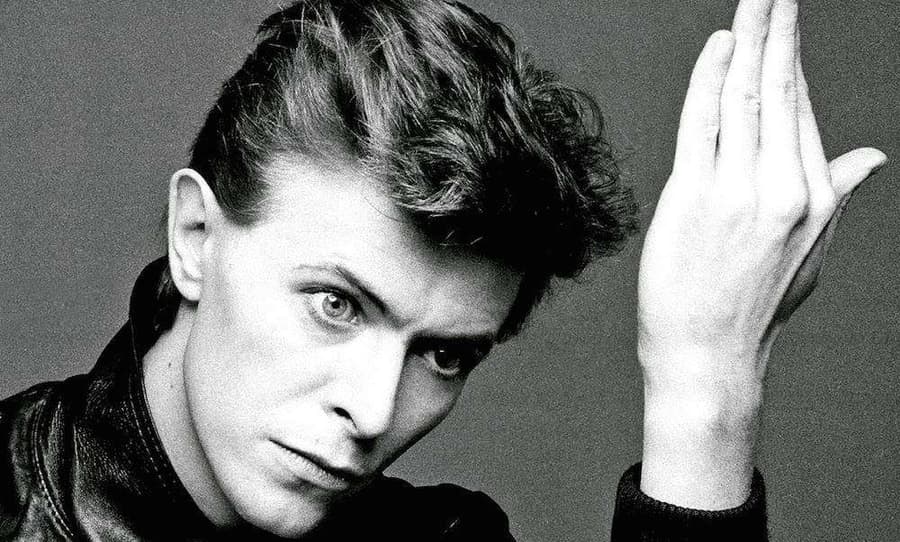

David Bowie‘s 25th and final album was released on January 8th, 2016 – his 69th birthday and just two days before his death on January 10th. At his right hand was long-time collaborator Tony Visconti who played a hand in crafting an album that was rich in experimental electronica and jazz – a thousand miles away from a sentimental swansong.

Blackstar was David Bowie’s farewell, yet it was anything but sentimental. Glistening with electronica and infused with jazz sensibilities, it was as experimental as Bowie gets.

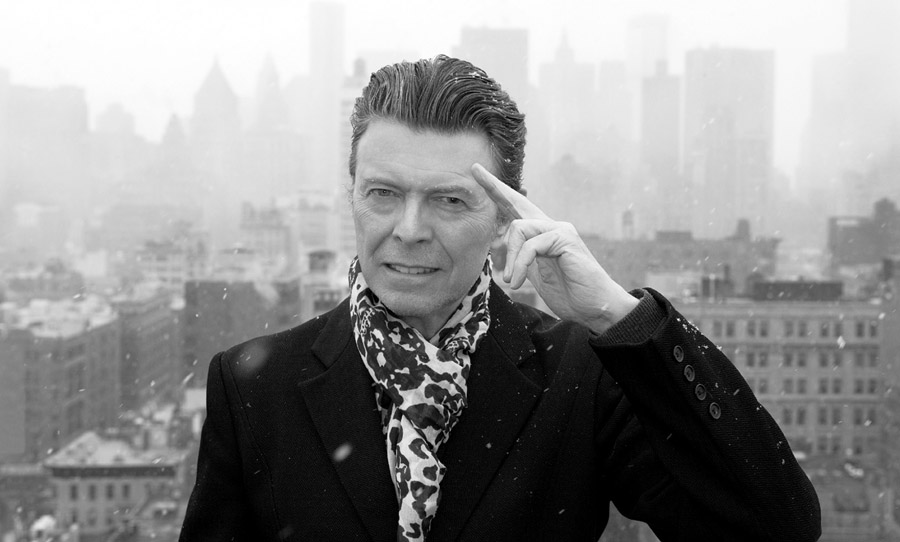

New York Story

A long-time New York City resident, Bowie obviously had ample opportunity to drink in the culture of the fabled metropolis. That culture, in turn, informed his art. Before the making of Blackstar, he realised one of his long-held ambitions – to create a stage play titled Lazarus, which would later find its way onto Blackstar in the form of a song.

New York also possesses a tradition of attracting the finest jazz talent to perform in its thriving live scene. David Bowie tapped a jazz combo – led by saxophonist Donny McCaslin – to be the band for the recording, after seeing the band play in Greenwich Village. The band also included Mark Giuliana on drums, Jason Lindner on keyboards, Tim Lefebvre on bass and Ben Monder on guitar.

With the exception of the saxophone and woodwinds, it reads like a pretty standard rock lineup. The resulting sound was anything but. Perhaps it was on account of Bowie’s illness (he’d been diagnosed with liver cancer 6 months prior to the sessions in early 2015), or just the freewheeling spirit that was made possible by assembling a group of New York’s finest players, but the bed track sessions for the whole album were done in three, one week spurts, with overdubs spread out over the following 6 months.

Creative Process

The dialog between Bowie and the band began with demos. Drummer Mark Giuliana told Modern Drummer about using Bowie’s electronic demos for inspiration: “I play some embellishments and some fills here and there, but the core groove is true to the demo. The drum sounds here are also inspired by the electronic palette.” The song he’s referring to here is the album’s title track, which is especially notable for its skittering beats and the most obvious reflection of the electronic grooves that were at the heart of the songs.

Visconti and Bowie were also taking inspiration from the influential and decidedly gritty hip hop flavours of the day. D’Angelo‘s Black Messiah and Kendrick Lamar‘s To Pimp a Butterfly were on high rotation during the sessions. To this end, Bowie further encouraged Giuliana to explore frenetic and hard-hitting beats on tracks like ‘Tis a Pity She Was a Whore.

James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem fame was also brought in on a few sessions, as Tony Visconti explained to Entertainment Weekly, “James Murphy came in in the February sessions and was kind of in an unassigned role, but he ended up doing some things. He had these vintage synths. He did some neat percussion sounds, some electronic percussion sounds — I think on Girl Loves Me.”

Welcome to the Magic Shop

The sessions took place in the Magic Shop Studios in SoHo, a stone’s throw from Bowie’s abode. The tracks were recorded through the studio’s Neve Custom 80 Series console into Pro Tools. The well-appointed studio also provided an extensive palette of high-end microphones from the likes of Neumann and outboard processing from API, Teletronix, Lexicon, Urei and more.

Despite the clarity and power that is the signature of the record, Visconti and Bowie took a liberal attitude to technical issues like spill. Mark Giuliana explained the approach to Electronic Musician, “I think the creative stuff came from utilizing other microphones in the room that might have not necessarily been drum mics. All the mics were open so they could have been used as such.”

Keyboardist Jason Lindner called upon an epic arsenal of tools to bring the brooding ambient soundscapes of Blackstar to life. Analog synths were high on the agenda, including a Moog Voyager and Micromoog, Sequential Circuits Six-Trak, an Oberheim Prophet 08 and 12. He also brought vintage keyboards into the mix, with a Hohner Clavinet, tack piano and a Wurlitzer electronic piano that formed the rich and bassy arpeggios on tracks like Lazarus.

In one way or another, all players brought their own extensive array of effects to the recordings. Guitarist Ben Monder used a suite of ambient pedals, including Lexicon LXP-1 reverb, Strymon BlueSky reverb, MXR Carbon Copy delay and more. Donny McCaslin’s avant-garde woodwinds were treated with Visconti in the midst of the session.

Bowie’s approached his vocal performances with a similar spirit of commitment and freedom. Visconti told Recording Academy that, “David always loved to do complete [vocal] takes, maybe as many as four. Usually, take one was the keeper with some words or lines used from the other takes. On rare occasions, he’d punch in.”

Beyond the recording and overdubs, the record was mixed by Tom Elmhirst (Frank Ocean, Adele, St Vincent, Beck) at Electric Lady Studios. Despite the challenge of mixing the title track – a ten-minute single which was stitched together from two songs – the whole album was mixed in ten days. And while Bowie was quite ill at this stage, his drive and encouragement was felt by everyone involved.

The urgency to create and commit to an artistic vision may have been hurried on by the fact that David Bowie was in a race against time. Elmhirst reflected on this possibility in an interview with Recording Academy, “I didn’t know it would be his final album. We even talked about working on another record soon. And he was very keen. There wasn’t a sense that this was it.”

Whether Blackstar was Bowie’s definitive final statement or not is in the eye of the beholder. What is for certain is that David Bowie’s relentless creativity, drive and freedom – the thread that ran through his life’s work – was also embodied in this record.