When exploring the crystalline grit that is the sound of Joy Division, one cannot go past the influence that producer Martin Hannett had on their music. Let’s take a look at how he shaped Unknown Pleasures.

Post-punk. A hyphenated word likely dropped on almost every music blog in the last week. The genre’s recent revival has become somewhat of a global occurrence, with bands like Diät emerging from Berlin, Protomartyr rhythmically driving away from within the heart of Trump country, and even a vibrant local scene here in Australia, spearheaded by Melbourne legends, Total Control, and being taken in new directions by the likes of Sydney’s DEN.

It would be tough to assert that none of these artists is familiar with Joy Division – it would be even more absurd to claim that none of these post-punkers is fans of the genre’s pioneers.

Almost three decades before the release of Joy Division’s debut LP Unknown Pleasures, another English band emerged with a sound born from the working class – four fabulous young gentlemen from Liverpool.

However, while the Beatles’ sound was a breath of fresh air amongst the austerity of post-war Britain, Joy Division embodied the industrial atmosphere of Manchester and the elbow grease (and literal grease) that drenched the bodies that inhabited the city. Even if it was never intended to.

Upon its inception, Joy Division wanted to be a punk band, joining the likes of their soon to be contemporaries: the Buzzcocks, the Clash, the Sex Pistols, Generation X and so on. Having found themselves at the same Sex Pistols gig, founding members Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook decided that punk music was something they could do themselves, and legend has it that Hook bought his first bass guitar the following day.

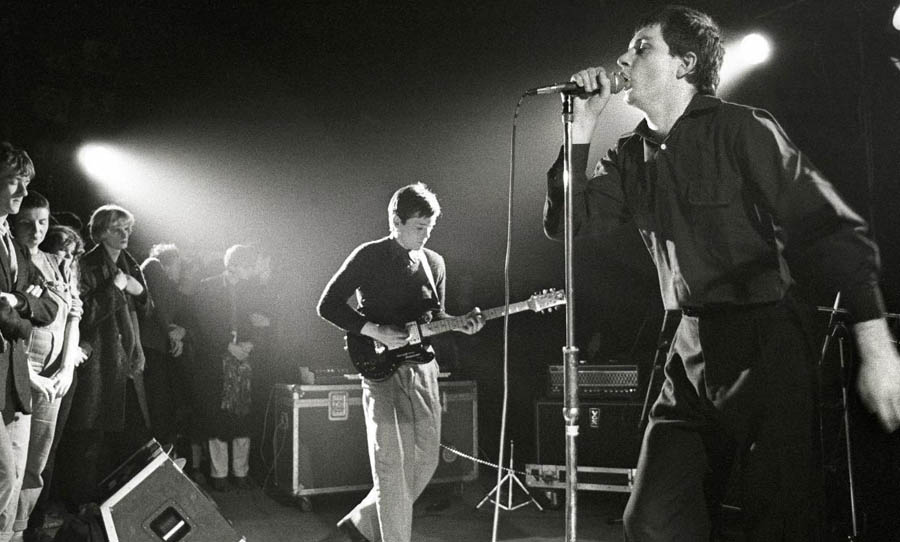

Joy Division was a band of two unique incarnations: their live act and their studio recordings. Sure, people will draw this clichéd distinction for many bands, but Joy Division set out to make punk music; they were going for loud, aggressive, and fast. And while there were notions of this on their albums, they were also very different from what the band originally intended to be.

Factory Records in-house producer, Martin Hannett, was the one who engineered the iconic industrial sound that came to not only define another punk band emerging from Manchester but an entire genre that lives on (and thrives) to this day. It was Hannett’s eventual manhandling of Joy Division’s aspiring punk tunes that would vault them onto the cornerstone of post-punk.

Hannett’s Madness

Probably the best introduction to Martin Hannett’s psychosis is a quote from Peter Hook: “In the studio, we’d sit on the left, he’d sit on the right and if we said anything like ‘I think the guitars are a bit quiet, Martin, he’d scream, ‘Oh my god! Why don’t you just fuck off!’”

That is but a taste of his antics.

Fuelled by heroin, marijuana, and god knows what else, Hannett was brilliant, elusive and difficult all in one. He would request the band do take after take, but rather than explicitly saying what needed to happen, he would vaguely demand, “do it again, but this time, more cocktail party” or “more yellow”. Once he famously asked for another take “slower but faster”, all in the same breath.

While some of his behaviour was merely wild eccentricity, occasionally his antics would become obsessive, verging on the edge of (or spilling over into) lunacy. He once reportedly heard a rattle in the drums and demanded that drummer Stephen Morris take them apart, right down to the nuts and bolts, only to have him set them up again.

Between demanding physical labour of band members, blasting air conditioning to frigid levels, and insisting that he must listen to the mix from beneath the mixing desk, Hannett was a real-life Frank N. Furter mad scientist type (though substitute the cross-dressing for a smack habit).

Are Those… Drums?!

This is a question one will most certainly ask oneself during the opening of She’s Lost Control. The answer? Well, sort of.

Firstly, a prominent feature of the drum sounds on Unknown Pleasures was Morris’ utilisation of a Synare, one of the first commercially available drum synths. The aforementioned track opens with a singular crack of this new-age technology, ringing out with an otherworldly hiss with each incessant crack for the entirety of the song.

Secondly, Hannett was obsessed with drums. And while he had previously incorporated drum machines into his mixes, he saw no need on Unknown Pleasures. He was also excitedly impressed with Morris’ robotic precision (so much so that he reportedly insisted that Morris record some tracks playing only one drum at a time, in some absurdly obsessive scheme to eliminate all possible bleeding).

While not relying on drum machines, Hannett was not solely satisfied with a dry drum sound and would go to insanely circuitous lengths to get what he wanted. One example recalls captured drum sounds being sent to an Auratone speaker perched on a toilet in the building’s basement bathroom, only to be re-recorded again through a single microphone, along with a din of spectral reverb.

Probably one of the most famous pieces of gear from the Unknown Pleasures sessions was the now immortalised AMS 15-80 digital delay unit. While sometimes used to ricochet the snare cracks back and forth (note the genius collaboration of delay and panning on Wilderness), more often than not, the delay was set to some minute period of time that affected the drums so subtly (look no further than the propulsive opener Disorder), that left the listener asking that age-old adage: “are those… drums?!”

An Eerie, Atmospheric Sonic Landscape

Hannett’s greatest achievement with Joy Division was, arguably, taking the aggressive songs they had been toiling away at and realising that they were so much more than a bunch of short, fast punk tracks. And this touch ensured that the Mancunian 4-piece would not be lost to the mists of time.

Hannett’s effective (it doesn’t need to be said, but why not, let’s just say it: brilliant) use of panning was just another way he managed to make the album seem as though it was recorded in some dark, damp seaside cave in the midst of a winter storm.

His extreme panning of the drum tracks moved the snare – which traditionally occupies the middle – all across the mix. While an instrument could attack one side of the mix, the delayed-release would be panned to the other side, creating a sound that was uniquely cavernous. Sure, Hannett’s experimentation with digital delay and Melos tape echo effects was revolutionary, but it was the outright absurd techniques he employed that allowed him to create so much space with so little.

Furthermore, Hannett’s non-music samples – notably the antique lift on Insight and shattering glass on I Remember Nothing, now considered classic Joy Division soundbites – served to further embolden the sense of isolation and despair so present in Ian Curtis’ brooding narratives.

Not to mention, on probably one of the more intense epics the album has to offer (New Dawn Fades), Hannett opens with an almost seemingly out of place guitar played backwards. Though, as the boys in Joy Division soon found out, it’s best to just let Hannett do Hannett, no questions asked.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbeNRHtpgOk&ab_channel=jarksjold

Convention. Who Needs It?

Something immediately noticeable about Joy Division is how much the bass sits at the front of the mix. Hook became known for his unique style of bass playing that incorporated mid-range tones and sometimes even drove the melody, leaving the guitar to sit further back in the mix, such as on Insight.

Apparently, this dynamic came to fruition as a result of the garbage equipment the band were working within their early years, with Sumner preferring the tone of his guitar when the amplifier was cranked to 11, forcing Hook to play higher to have any chance of hearing his bass lines. Hannett latched onto Hook’s trebly bass lines, diluting Sumner’s guitar work behind layers of reverb, and nestled them in unconventional locations in the mix.

Giving the Band Exactly What They Didn’t Want

When the recording was all done and dusted, the band was less than impressed with Unknown Pleasures.

The loud, aggressive sound they had set out to create had been replaced by a dark, brooding, and downright depressing compilation of Hannet’s self-indulgent experimentation. While Curtis reportedly loved where Hannett had taken the record (most likely because the tone now delightfully complimented his tortured lyrics), the rest of the band felt a bit slighted.

Most of the mixing had been done at inopportune times, like the early morning, with Hannett ducking into the studio to mix everything how he saw fit. He very much saw the album as a chance for himself to let loose and experiment, supposedly saying of the band, “They were a gift to a producer because they didn’t have a clue. They didn’t argue.” After the album was released to critical acclaim, the band decided it was best to swallow their pride, ultimately opting to indulge Hannett one last time on their second, and sadly, the final album, Closer, released a year later.

Hannett’s work on Unknown Pleasures produced something so stark and brooding it pairs perfectly with the now-iconic album cover: a black background with a framed diagram of layered, successive radio pulses of the first-ever recorded pulsar, or imploding star.

To imagine the isolation, despair, and sheer magnitude involved in a collapsing star, one needs only to throw on Unknown Pleasures in pitch darkness and let the collaboration of aspiring but misguided punks, a tortured lyricist, and one lunatic producer fill in the darkness with the expansive space it is so chockfull of.