The Yamaha CS-80 is a glorious mess of contradictions, entering and exiting production within four short years, but still changing the course of history with its sound.

The ‘70s saw incredible leaps forward in music tech, many in the realm of electronic instruments. The record industry had reached a new level of maturity in its evolution and the competition for creating and recording new sounds was fierce.

Bob Moog, Alan R Pearlman and Sequential Circuits were locked in a battle for synth supremacy in the States, while Roland, Korg and Yamaha were in their own race on the other side of the Pacific.

In 1976, the Yamaha CS-80 marked generational change in synthesizer technology. Widely regarded as the first great synth to emerge from Japan, it changed the way composers approached the instrument, setting a new standard in expression and exploring new depths of sound.

Analog Heart

The synthesizer is only as strong as its elemental components and at the heart of the CS-80 are high quality oscillators. The three flavours of waveshape include the sine, square, sawtooth alongside a white noise generator.

After the oscillator section, the filter section features a high pass and a low pass filter for each of the two voices (more on that later), with adjustable resonance. Finally, the amplifier section features two discrete level controls and unusually, a sine wave oscillator.

All pretty standard design elements for a classic analog synth so far, but this giant had some unique design characteristics that made it a decidedly singular instrument.

Firstly, the CS-80’s extensive polyphony was unusual for its time. The eight voices made it a favourite for musicians looking for wide, deep and luscious detuned pads and brass sounds, which could be effortlessly wide spectrum, or harsh and piercing – especially if you make use of those filters and resonance controls.

Chief among the Yamaha’s distinguishing internal features is the doubling of its internal architecture with Voice I and Voice II being independently controllable.

There’s also a powerful ring modulator section, with a dedicated attack and decay controls as well as the standard parameters like speed, depth and modulation amount sliders. In terms of sheer sound sculpting horsepower, it’s a V8. On steroids.

Despite the generous proportions of the CS-80, it took inspiration from an even bigger synth in the Yamaha stable – the GX-1 (most famously used in Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s version of Fanfare for the Common Man).

This beast was the size of a small piano and resembled something close to cathedral pipe organ – right down to the pedals and its multiple keyboards – plus, it had even more polyphonic capability than its more popular descendant.

The GX-1 was never going to be a big seller – the size of the price tag was in proportion with its physical dimensions. Despite being close to 100 kilograms itself, the CS80 was positively portable in comparison, featuring only one keyboard.

High-Performance Machine

When this instrument hit the market, it didn’t make much more than a ripple. This was attributed to its expensiveness, somewhat awkward front panel interface and its back breaking dimensions. It was also up against the other innovative polyphonic synths – like the Sequential Circuits Prophet 5, whose sleek, stylish lines and relative affordability provided more than stiff competition.

The actual playing experience of the flagship Yamaha, however, was anything but ungainly.

The velocity control and aftertouch on the CS-80 made the modular rigs of the time look like lab equipment. This coupled with the weighted action keyboard made the synth a serious performance machine for pianist/composers.

There are also improvisation-friendly faders that are handily positioned close to the keyboard – like brilliance and resonance – for the global sweeping of frequency cutoff points and resonance. Also, there is simply a single fader for switching between the synths two voices, which makes for pretty dramatic tonal shifting potential, right under the fingers.

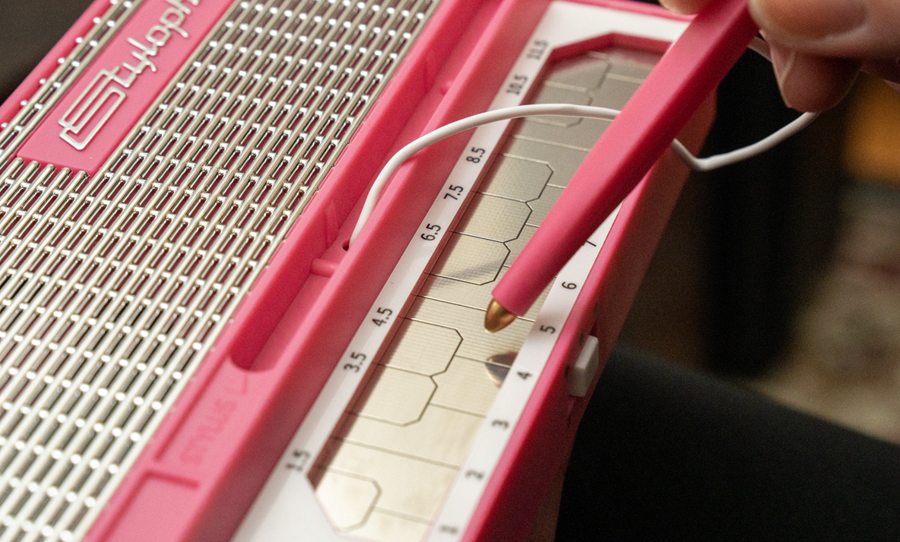

Even more innovative is the ribbon controller, which has gone on to be emulated in modern MIDI controllers and synth keyboards. It can be set to control pitch or the filter and is just the thing for those sweeping, dramatic glissandos.

The preset buttons just add to the mystery of the design. Any synth builder in their right mind would be loathe to include such a crass feature, yet, what a feature! With a flick of a switch, you can dial in some of the most quintessential synth patches in recorded history.

Famous Fans of the CS-80

As mentioned previously, CS-80 was a lot of synth for the average punter to handle. Expensive and bulky, it didn’t really scream “mass market”. Where it did make a sizeable impact was at the highest levels of studio practice.

In the early days of the CS-80, it provided the inimitable chord stabs in Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean, it filled out Toto’s Africa with its fat, lush pad sounds and offered up the squelchy, resonant rhythms on Paul McCartney’s Wonderful Christmastime, triumphant fanfare of Bruce Springsteen’s Born In The USA and more than a few other chart-toppers.

Of course, there is one exponent whose relationship with the instrument would become the stuff of folklore – Vangelis. His iconic Blade Runner soundtrack is the exemplar of everything that we’ve come to know and love about the synth – its woozy, searching brass tones were made possible by the CS80’s internal design, as well as the way it invites experimentation, with its unconventional yet intuitive performance-friendly ergonomics.

Bringing it Back to Life

In these economically rational times, the acquisition of such an unwieldy analog dinosaur is beyond most mere mortals. The software emulation that has gained the most plaudits is the Arturia CS-80 V, yet there are some hardware developments have also grabbed the headlines of late.

The Deckard’s Dream from Black Corporation is a relatively new release that eschews the keyboard in favour of a rackmounted unit. It has a similar aesthetic composition and performance capability of its illustrious ancestor. Also weighing into the debate is Behringer, who have teased the idea of a remake, but at the time of writing, have yet to confirm whether they’re going to attempt a clone.

Most intriguing was the recent speculation about Yamaha themselves breathing new life into this elite instrument. No further progress has been made on this front, which is understandable.

After all, it would be very expensive – which is very much against the trend, but with a few notable exceptions. And, if anyone was to complete this resuscitation of Jurassic Park proportions somehow on the cheap, would it be the same synth?

This question is the most difficult to answer. If any reboot were afoot, surely it would have to include modernisations that make it more congruent with a modern production workflow (MIDI integration, comprehensive memory and preset management, among others). Ironing out all the kinks might dilute its identity.

And if the holy grail of a CS-80 for a new generation does not come to pass – we’ll simply have to marvel at the one we already have. A sophisticated performance machine, with some bewildering attributes.

A polyphonic leviathan, whose scope was still somehow limited. A lumbering monster, that was ahead of its time.

In other words, one of a kind.