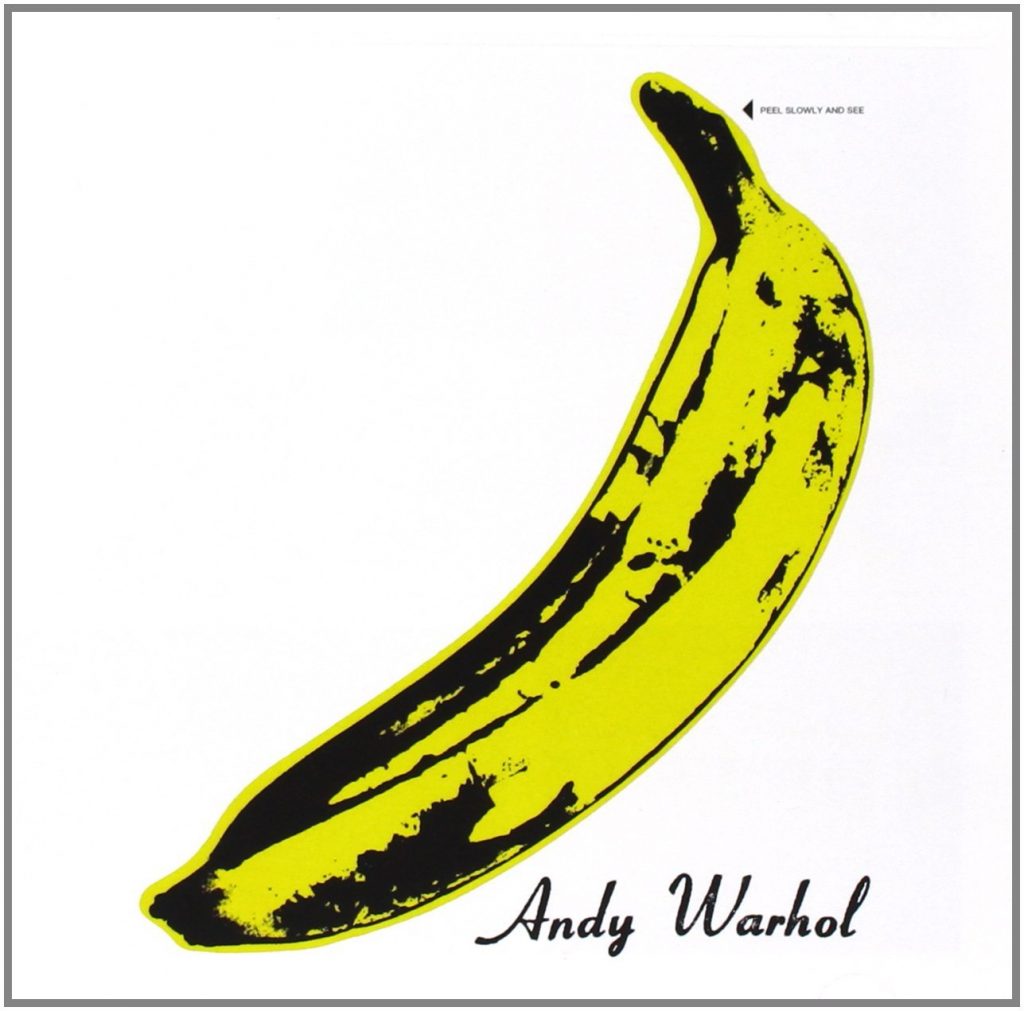

The Velvet Underground and Nico embodied the ultimate album ideal: how the creative influence of five musicians could inform the next twenty years of music.

The Velvet Underground and Nico embodies a seldom realised idea: that music really can change the world. A financial failure in its time, the loose collection of these New York artists’ self-titled debut took a decade to sell 100,000 copies.

However, despite its commercial failings, The Velvets’ humble flop was a primitively bright conceptual spark. While simultaneously hitting the bargain bins, greater forces were at play. Ripples of inspiration were subtly mutating the face of popular culture. A powerful influence, the group’s deep-seated creative forces unified into something truly iconic.

Over a prolonged period of gestation word of mouth built in the musical underground. The innovative album passed hands while outspoken critics like Lester Bangs lionised the group’s achievement. To cite Brian Eno’s famous remarks to the LA Times in 1982:

“I was talking to Lou Reed the other day, and he said that the first Velvet Underground record sold only 30,000 copies in its first five years. Yet, that was an enormously important record for so many people. I think everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band!”

A central reference point in seemingly every shake-up in rock music since its release, generations of unrelated musical movements drew something different from between the vinyl grooves. Post-punk, glam rock, art rock, new wave, noise, and even industrial can trace their twisted lineages to the iconic album. Its influence still courses fluidly throughout modern music, and remains a seminal name-check for anything primal and completely outside the norm.

Commercial pressures, powerful personalities, and creative impulse can often lead to compromise in a band. The Velvets were by no means immune to these factors, but what is remarkable is how true each creative contributor remained to their individual inspirations.

Take a moment to profile the unlikely constituents which gave rise to the sonic schizophrenia of the band.

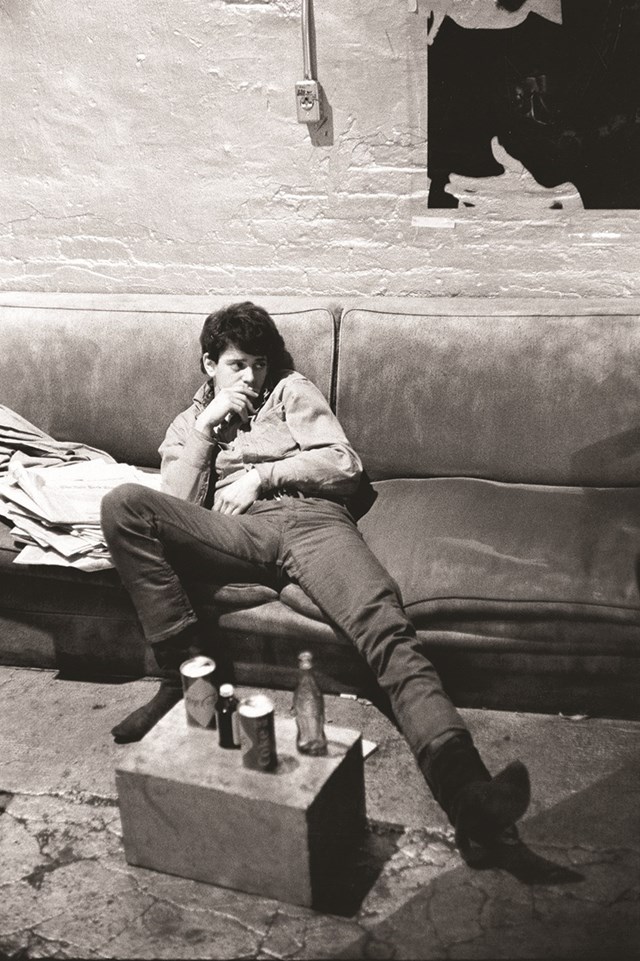

Lou Reed was the cantankerous black sheep of a middle-class Jewish family. Informed by literary studies and a stint in a mental institution at age 17, Reed looked to expand the idea of what popular music could entail. Musically the young songwriter cut his teeth churning out Motown, surf rock, and bubblegum pop soundalikes for the unscrupulous Pickwick Records.

Yet the Long Island native sought to follow in the steps of the visceral literature of William S. Burroughs and his beat generation forbears. Hidden behind the clichés of rock and roll, Reed saw an unlimited potential to accommodate a broader range of meaning.

Breaking down the barrier between rock music and poetic narrative, Lou injected sleaze and degradation into rock. At a time when puritanical values and obscenity laws could still place a chokehold on the avant-garde, Reed sang about heroin, transvestites and rent boys.

Yet the band didn’t kick off as some grand artistic endeavour. Looking to capitalise on a more contrary sound, Pickwick encouraged Reed to bring together a mock rock group to perform single Ostrich live. Known as The Primitives, the group started gigging live, securing a fortuitous residency at New York’s Cafe Bizarre in 1965.

Playing alongside Reed at this time was John Cale. A Welsh emigrant, Cale was an acolyte of the avant-garde. After finishing his study in London he relocated to New York in 1963, where he made a name for himself playing alongside influential neo-classical musicians like John Cage and Terry Riley. The young artist was probably just as happy to play a single piano chord 50 times with his elbows as anything else, but after meeting Reed at a party, he agreed to join his group.

Sterling Morrison was a Syracuse University graduate who was invited to play with The Primitives after a chance meeting with Reed, his old high school acquaintance, on a Manhattan subway. Contributing a more conventional grounding to his counterparts, he provided both rhythmic bedrocks and duelling solos to ground Reed’s more obtuse fretwork. Leaving the band in the early ’70s, Morrison would evaporate from popular music entirely until a brief return in the early ’90s.

Filling in for Primitives’ drummer Angus MacLise, Maureen “Mo” Tucker’s biting percussive edge kept the group together. Like Cale, Tucker looked to music from further afield when informing her self-tutored approach. While MacLise had introduced ideas from eastern music into the band’s sound, Tucker made an even greater impact with her appetite for the African beats of Babatunde Olatunji and the economic rhythms of Bo Diddly. The metronomic Tucker provided a viciously pervasive thump. She would only play standing.

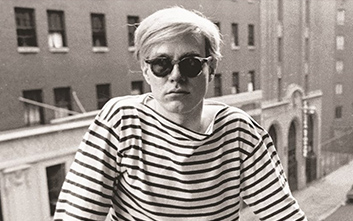

Indirectly Andy Warhol remains one of the great unacknowledged influences in popular music. Although he did little in helping the group sculpt its sound, few would deny his influence in fostering their attitude and style.

“The Velvet Underground was part of Andy’s group, and Andy wasn’t part of anything,” Reed told Spin in 2008.

Even prior to meeting The Velvets, Warhol shared many links with the group. Andy was familiar with avant-garde musicians La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, both of whom had played with Cale in the Theatre of Eternal Music. This aristocrat of the New York scene also had associations with artist Walter De Maria, a drummer from an early iteration of The Primitives. Introduced through a shared acquaintance, Warhol quickly extended his patronage to the fledgling Velvets.

As art took an interest in popular culture and the mundane, pop and art collided with the Velvet Underground. Trashy could be classy. Ugly could be beautiful. He deconstructed consumer culture and captured unfiltered depictions of modern life. Like Warhol, Reed and company were particularly engrossed with that which was ignored or glossed over by the mainstream. As manager of the group, Warhol impressed into The Velvet Underground the idea that everything and anything could be art.

It was with Warhol’s patronage that the group was brought into the nexus of New York’s underground scene. The group transplanted from Cafe Bizarre to The Factory. With Warhol’s encouragement they become a house band and the sonic centrepiece of Warhol’s multimedia phenomena the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.

The group’s immersion within the polaroid art world of Warhol’s Factory placed them within a surrealistic scene where hustlers, transvestites, socialites and living theatre converged. Warhol would also help co-finance their debut album along with Norman Dolph, a Columbia Records sales exec.

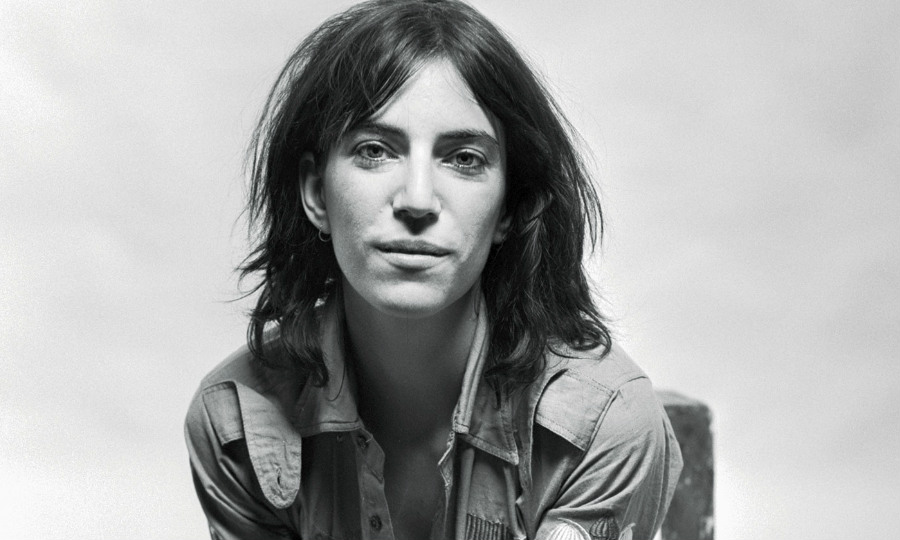

Chanteuse Nico was a late addition to the band. Thrown in by Andy Warhol, it was his belief that the chic actor, model, and vocalist could provide the group with some extra edge. In his on words the group were lacking a much needed “charisma”. Noted for her acting in French drama La Dolce Vita, the femme fatale’s icy persona belied a burgeoning (if moth-like) creative impulse. In line with Warhol’s fetish for film, she lent a detached and cinematic quality to the group.

Her injection into the band was far from a smooth transition. The German expat struggled to find acceptance amongst her peers. She would often clash with her bandmates due to her partial deafness and general eccentricity. But with her addition the cards were stacked; recording the album in early 1966, the group had few creative restrictions other than the ubiquitous clarion call of “no blues”.

The deceptively tranquil Sunday Morning opens the album with sweetened pop. A crooning Reed embodies an effortless cool. Jangled guitar and beguiling innocence provide a moment of alluring misdirection, while subtly paranoiac lyrics anticipate the album’s darker undertow.

Things take a turn towards the more abrasive with Waiting For a Man. The second track’s lyrical world is intended to be real. Relating the details of a drug exchange, it weaves outsider depictions of the stark realities of street life and subterranean culture. A jilted piano echoes the Tucker’s juddering pulse.

With all the defiant deviance the group can muster, I’m Waiting For The Man conflates drugs and sexuality. The song lives within a reality aligned against the prevailing values of the day. It conveys a sense of moral decay which would see the record banned from major retailers and banned from radio airplay. Reed is the model of passivity and dependence. As raunchily as the song resounds, its feeling is voyeuristic.

While earlier tracks exude desperation and the idea of living on the edge, Femme Fatal swirls into gentle fantasy. The track places Nico in central focus. Her alluringly deadpan vocals are carried above a baroque chord progression.

The velour S&M fantasy of Venus in Furs verges on hypnotic. While the band averted themselves from the lysergic ripples of West Coast counterculture, it’s difficult to classify the paradoxical Venus in Furs as anything but psychedelic.

Run Run Run raggedly demonstrates the group’s celebration of stupidity and ugliness. Musically they revel in circular-minded banality. All Tomorrow’s Parties makes musical sketches of Warhol’s Factory scene.

Despite Reed’s contentions that he wasn’t glorifying anything in his music, Heroin provided a directness and frankness about substance abuse which made the missives of counterculture seem childish in comparison. Cale’s sound experiments drone over the ostinato of a two-chord motif. Tucker’s percussion imitates a pulsing heart before inexplicably dropping out. Out of tune, primitive and never far from falling apart, here the group remain vital at every moment.

The punchy There She Goes Again situates itself as a straight ahead rocker, albeit one incorporating elastic time signatures. I’ll Be Your Mirror shimmers, while The Black Angel’s Death Song teeters into formless noise. Closer European Son pays homage to poet Delmore Schwartz while distortion and feedback dominate the album’s dissonant conclusion.

The black-clad Velvets would not last long. The group quickly parted ways with Warhol and exited The Factory scene in ’68. Nico and Cale would also depart. After dropping another two albums the group had all but disintegrated. 50 years onward the beauty and rawness of the group’s untamed innovation continues to resound throughout popular culture.

Much of music’s modern history has crossed currents with these New Yorkers’ commercial folly. It provides proof of concept that a group of individuals can instil music with a sense of intelligence and meaning. The Velvet Underground and Nico remains an enduring cornerstone of popular culture, echoing through time with an unwavering magnetism.