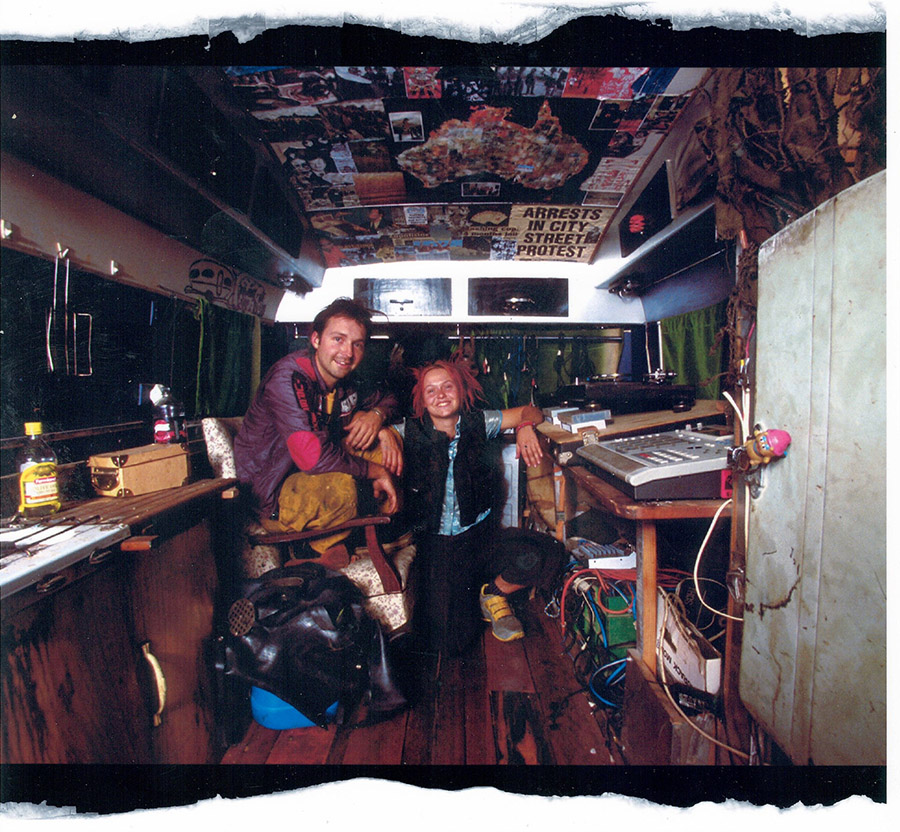

After sitting down with Monkey Marc, I find it almost impossible to believe I first heard his name just six months ago. A veteran of several scenes gone by, Monkey Marc has played a hand in everything from Sydney’s late ’90s squat rave culture to a series of mobile musical protests outside mid-Australian uranium mines.

Fiercely environmental, Monkey Marc’s life has been mostly nomadic, traversing Australia with a solar powered sound system in tow (which packs down into a rehashed motorcycle caravan). His studio in Melbourne is similarly compact, a museum of vintage gear crammed into a shipping container, which also runs on solar energy.

It was here that we met, and settled down for what turned into a long, long chat. Surrounded by machines with less than 10 seconds of sample time and a Space Echo that was probably older than I was, we had a chat about, well, pretty much everything.

This article will be published in Happy Mag Issue 6. Order your copy here.

Stowed away in his solar powered studio in suburban Melbourne, Monkey Marc lives a secluded life for someone so apparently instrumental to Australian music history.

HAPPY: We have a fair bit to talk about…

MONKEY MARC: Oh, god!

HAPPY: I want to start early, because I don’t actually know too much about your early days. You were doing illegal parties in Sydney, all these places you originally took the sound system to. Was that as Monkey Marc?

MONKEY MARC: Well Monkey Marc, and we used to have a crew called the Lab Rats, we were a solar powered sound system. This is going way back, I’m starting to show my age now. I came across to Sydney when I was 13 and then got influenced by the Sydney underground techno scene. That punky ethos, free shows and DIY sound systems, Reclaim the Streets, the Vibe Tribe, Non Bossy Posse, that whole early revolutionary party scene was such a fantastic time to be around. I was always inspired by that, and I ended up taking a sound system on the road and that ended up taking me into the desert where I did a lot of protests with lots of Aboriginal elders at the uranium mines. Hence, that’s why my sound system became solar powered. Our vehicle at the time ran on vegetable oil, ‘cause we had no money. This is like ‘98, ‘99.

HAPPY: I have to ask if you have an engineering background or something? Some of this is, actually, really impressive handiwork.

MONKEY MARC: I guess you learn from your mistakes over the years! I don’t have an engineering background but I’ve also been lucky to have a lot of great friends who are really talented, and I’ve learned a lot just through that scene I’ve talked about. This amazing, fruitful DIY scene that Sydney was famous for in the ‘90s and into the 2000s.

HAPPY: Where does Combat Wombat fit into that mix?

MONKEY MARC: Combat Wombat came out of the Lab Rats sound system. We decided we needed to start making our own music. For me, I was influenced by a band called the Non Bossy Posse, who were a political techno act. They used to have this rough, ravey techno, using samples from the radio or speeches about the issues of the time. I used to see the impact of that, and so Combat Wombat really came out of the fact that there really was a lot of potency to what they were doing.

We started to write a few tunes and, at the time, we were squatting in Sydney in a place called the Broadway Squats just near Victoria Park. It was a massive squat, there were three huge houses on the main street and a big warehouse out the back, we had two or three kitchens, we had a recording studio, we had a massive venue on the top level with a mirror ball that was about the size of a room. There we met Elf Tranzporter, a rapper who was in a band called Metabass’n’Breath and we decided to write a hip hop song with as many political ideas and concepts that we had been exposed to. That was really the start of Combat Wombat, it brewed out of that Sydney squat party scene.

HAPPY: Awesome.

MONKEY MARC: We’re still going! 350 years later…

HAPPY: It’s been quite difficult to get a hold of all the things you’ve done, it’s like this huge spider web.

MONKEY MARC: Maybe I should write a point form novel.

HAPPY: When did the solar studio start happening?

MONKEY MARC: Funnily enough, the studio used to be in a caravan, it used to come along with the vege oil van. So the first Combat Wombat album was pretty much written in this silver bullet caravan with solar panels on the roof. It eventually fell apart, and I couldn’t get the thing registered any more… it had travelled many thousands of kilometres. We had done a bit of recording with a friend of mine who had a shipping container studio in Melbourne, and I was really inspired by them. He goes by the name of Countbounce, and produces for a lot of people like Ash Grunwald. We ended up mixing the first Combat Wombat record there and I thought “I want to do my own”. Built the studio with a friend of mine, everything was built from what we could find, hence why half the studio is built from an old basketball court. Now what you see is the essence of that, but the idea has always been the portability factor, and being entirely off the grid. One, for my own consciousness and for my ‘practice what you preach’ mentality, but importantly to showcase that it works. If someone like me can do it, who just goes out and follows a passion, then anyone can do it.

HAPPY: This is the original container?

MONKEY MARC: Yeah, it’s just gotten fuller. I’ve become a bit obsessed.

HAPPY: I do love some organised clutter.

MONKEY MARC: That’s a great way of putting it!

HAPPY: Is it constantly changing, or is this a bit more of a happy place?

MONKEY MARC: This is pretty good, I’m pretty happy at the moment. It’s been a lot of years in the making, I write music, I mix music and I master music all in here, so I’m pretty happy.

HAPPY: A one stop shop. Is there any way the solar aspect limits a studio?

MONKEY MARC: Well, yeah. The only limitation is that you can’t go 24/7. So five to six days a week of studio time is good, but I usually try to leave a day and half to two days off to let the batteries recharge.

HAPPY: That’s really obvious, I hadn’t even thought of that.

MONKEY MARC: Yeah, and funnily enough the power is much cleaner than house power. You just get this very pure signal, it sounds funny to say it but you don’t get the buzzes or the nasties of industrial power. Plus it’s your own fault if the power goes off. You’ve gone too long, it’s time to go home!

HAPPY: The gear I’m seeing is very old school. Is there a tape machine in here?

MONKEY MARC: There isn’t, that’s a whole new level of fixing. But I have plenty of stuff that can emulate that sound. Most of the things I have, have a unique sound, or a quality to it.

HAPPY: I think you just succinctly described why people love old gear. It all has this real character.

MONKEY MARC: Well it’s like a guitar. You know, people say “I only play a Fender Strat”, or “I only play a Les Paul”, they have a sound. You turn it on and say “oh, that’s Angus Young from AC/DC”, or “that sounds like Keith Richards”. People forget that this gear has that particular sound, you know? It was designed in an era when it was high technology. I mean, this thing here has 10 seconds of sample time. People look at me and go, “what the hell?”. So they’ve got a sound, but they also have a fantastic limitation that really pushes you into an area, makes you make music in the same way.

HAPPY: I like that idea. It forces a certain creativity out of you.

MONKEY MARC: It does, and it creates your sound.

HAPPY: Is there a romantic feeling too, for you? For some of this old stuff?

MONKEY MARC: It’s funny, now people look at me and it’s almost like this working museum, but this is what I knew. I started writing electronic music in the late ‘90s and this was the gear, you know? I’ve always had these things around me, so there’s a practicality to the fact that that’s what I know, but there’s definitely a sentimentality as well. There are so many practicalities about loading up a computer and having a million different plugins but there’s just something nice about this. You think in a different way, it’s quite liberating. If I spend 10 hours making music on a computer, it’s quite different. Here I can hit things! Knobs! It’s a bit more like playing music, there’s a real tactile, fun and tangible excitement to it. I find it much easier to write like that but I can also understand, when producer friends of mine come in here, they just go “this scares the fuck out of me”.

HAPPY: Can you tell if someone else is using old gear?

MONKEY MARC: There is a certain edge to it, but there’s certainly a lot of great producers who use software as well.

HAPPY: There’s quite the software vs. hardware debate going on right now.

MONKEY MARC: There is, it’s a very strong debate. I tend to stay out of it, because…

HAPPY: You’ve made your side clear?

MONKEY MARC: It’s working for me, I’m happy. They can argue whatever they want.

HAPPY: Outside of the studio now, you recently went to Jamaica do to a couple of records. Jamaica has been so important for music in the past, but perhaps underappreciated. What was it like there? Apparently now it’s almost a dead scene, even quite sad.

MONKEY MARC: Life’s tough in Jamaica. They had a really thriving record industry, which is unfortunately really flat at the moment. There’s only one press being brought back to life. So as far as selling music in Jamaica, or buying music in Jamaica, artists are finding it really hard. But it’s just had such a huge influence for an island of, what? 3 million people. It’s insane, it truly is one of the most bizarrely creative places I’ve been to on the planet. There’s also this really interesting, small town mindset to Jamaica that really makes things possible. You can actually meet stars, and the talent you’ve grown up with on record.

HAPPY: Like?

MONKEY MARC: Well, before I get into that, I went to Jamaica because I’ve always wanted to go….

HAPPY: I was going to ask, was it your first time?

MONKEY MARC: Yeah. The opportunity came up because Kim was over there, she was learning a lot of dancehall dance, which is a massive thing over there. I went over to visit and thought ‘I’ll bring my gear’ but I was only going to make a few songs. You go in mildly unprepared and next thing you know, it’s all on. I met one or two guys through Kim’s links, through some dancers. It started off being a little cheeky because they didn’t really know who I was, I was just some white dude, but then the first guy I linked up with was called Fantan Mojah, he was eating a coconut outside a corner supermarket. He was looking like a record! You could have taken a picture and that was a record, right there.

He was a proper hustler, he’s a real rasta, a proper hustling gangster rasta. I really like him, he’s a really nice guy but he knows how to make stuff happen. I gave him a song he really liked one night, and the next day he called me and said “You need to come over now. Jump in a taxi. Meet me at this place, we’re going to meet up with this artist.” So went to this place a couple of kilometres up the road, it’s painted proper rasta colours and there’s this guy out the front with this meticulous lawn and we go inside and then there’s all these rastas on one side, then there’s all these young looking, kind of gangster dudes drinking Hennessey on one side.

HAPPY: Is this real?

MONKEY MARC: This is real. And this was Capleton’s house. For any reggae fans out there… in Jamaica he’s known as The King. He’s big, you know? And I was making a tune with this guy! The thing is, when you make a song with someone, when you’re picking someone like Capleton who’s a world famous reggae star, word gets out. The next thing you know, his garden is full of people, and he’s literally blaring my music out of his sound system and writing the song, basically rapping it out. People were say “you gotta go stand next to him, he’s got a vibe with you”. I’m standing next to him, I’m talking ideas and he’s just singing back to me and next thing you know it’s about 9 o’clock at night and he says “We’re going”.

I just jump in the car and we go off to this industrial estate. There’s a studio, and there’s this massive sound system out front of the studio and a huge party. We walk in with Capleton and everybody’s just looking. One of Capleton’s guys goes over to one of the sound system guys and just goes “We need quiet.” So they turn the system off at this massive party and we walk in and we record Capleton and Fantan Mojah, these two reggae dancehall legends, then come out an hour and a half later and then the guy gives the nod, and the sound system turns back on. And that was the first recording session. But there’s many stories like that. There’s Ninjaman, there’s others.

HAPPY: Completely ridiculous.

MONKEY MARC: It’s beyond hyperreality, Jamaica is almost unbelievable and way different than what I expected. I don’t even know what I expected, but it was full on. You’ve got to have your wits about you, it’s a massive hustle. You know, because everyone’s very poor it’s very difficult to actually survive in Jamaica. So when somebody comes in to do stuff, you’ll have queues of people finding out where you live, knocking at your door trying to sing at you. I’d be in recording sessions, like with Ninjaman. This is a guy hardly anyone can get in the studio, he’s a whole other level. He’s this whole other world, what they call Badman, he’s this real tough dude. While I’m recording him, I’m sitting in the booth, I’ve got young guys walking into the studio playing me their songs on Youtube and singing at me. I’m talking like, at least 30 guys did this, and I’m trying to record this one song and everyone’s going for you. For them, this could be their only opportunity.

HAPPY: To the point of intimidation?

MONKEY MARC: Oh yeah. I nearly got involved in massive punch-ups, there was guns involved and some other things… that’s part B of the story. That’s next week’s edition.

HAPPY: Sounds like a real experience. Are you going back?

MONKEY MARC: Definitely. But I’m taking a little break before I go back. In Kingston, kindness is seen as weakness. If you’re there being your general self, it’s seen as a weakness. It’s a challenge. But I recorded an album! It’s the kind of place you can go and four weeks later you leave and go “what the hell just happened?”

HAPPY: Jamaica, woah. I thought that would be a small part of the conversation. Guns?

MONKEY MARC: Guns! Oh my god, it’s so ghetto.

HAPPY: Well… the other thing I want to talk about is the Australian stuff. It seems like you have a strong connection to the Northern Territory, did that come out of the protest days?

MONKEY MARC: Yeah, that goes back to the Lab Rats days and Combat Wombat, when we used to go out to the northern parts of South Australia near Lake Eyre and protest Roxby Downs. People started saying “well, we’ve got all these kids in communities and you guys have got all these skills. Why don’t you help out?” That really started the whole thing, so that was the late ‘90s, early 2000s. We were still running off nothing, it was Mad Max you know? We just kept getting invited up north and eventually we moved into the Northern Territory, and that started that link with music workshops and video workshops with young kids. With elders too.

HAPPY: Nice, I mean from my limited interactions with NT it seems like one of the more supportive music scenes around Australia. Definitely smaller, but that probably has something to do with it.

MONKEY MARC: Smaller and more spread out. But lots of good stuff happens in Northern Territory, people recording each other and helping each other out. Because it’s huge. The Barkly area where we did the workshops, the Culture program where we met Kardajala Kirridarra and the Desert Hip Hop crew, I think it’s the biggest council in the Southern Hemisphere, it’s huge. It’s 800, 900 kilometres long. So your first workshop, you’ll have to drive like 850 kilometres and do that, and three days later you drive another 750.

HAPPY: And you’re still in the same council!

MONKEY MARC: You’re not even in the next community!

HAPPY: Kardajala Kirridarra are still somewhat of a mystery to me, that’s where you found them?

MONKEY MARC: Kardajala Kirridarra came out of the Barkly Desert Culture program. A guy called Sean Spencer got a youth diversionary grant about three and a half years ago and decided to do a big multimedia program, which is when he contacted me. We didn’t have much of a strong idea but we had to have a youth aspect, mainly dealing with youth at risk. Kardajala Kirridarra are based north of Elliot in a place called Marlinja. It’s at the edge of the desert in the southern tropics, in this place where all of the rivers come in. Eleanor Dixon, she’s sort of the key lead singer for Kardajala Kirridarra, that’s where she lived.

When we started the program I got Beatrice Lewis to come out because I knew she’d be the perfect person to work with these ladies. For the first six months we were doing work in about six different communities, but Beatrice formed a really strong relationship with Eleanor and Janey Dixon, so that started evolving very naturally and they started writing songs in that area. We’d go out for these big long recording sessions, both myself and Beatrice, we’d have to make these makeshift studios in old halls that didn’t have any power… we were recording in places with no windows and broken air conditioning in the middle of summer, in subtropical heat and our computers were dying. So funnily enough, a lot of that album’s vocals were done in these really tough conditions. When I listen to it back with the headphones you can almost hear the storm brewing, and the birds, and the dogs in the background.

HAPPY: There’s only one thing left. Apparently you’re releasing quite a lot of music next year?

MONKEY MARC: Well, I am. I’m releasing two albums and about four EPs. One of the albums is the Jamaican album that we were talking about, that’s going to be called Vital Sound. And there’s four EPs related to that, and No Surrender was the first. I’ll release those, then I’ll release the album. The second album I recorded with a guy YT, he’s a great, really politically conscious guy, and was quite a bit of a star in the reggae scene in the UK. Very unusual guy, he’s white as well, hence the name YT. That album will be called Question Everything, that’s coming out sometime next year as well.

HAPPY: Excellent.

MONKEY MARC: Plus I’ve got a single that just came out! Last week, on a record label called JAHTARI. So lots of new music.

HAPPY: Lots and lots.

MONKEY MARC: Don’t know how I squeeze it in…