Melancholic and mysterious, the Mellotron belongs perfectly to its time, and yet still carries a lasting legacy. What was the tale behind this idiosyncratic instrument?

The Mellotron is an instrument unlike any other. An early kind of analog sampler, its use of tape ensures that no single note is ever the same. Speaking on its influence in the ’60s, author Thom Holmes describes it as an instrument that “lent an eerie, unearthly sound to the music of many rock bands.”

Initially adopted by the likes of The Beatles, David Bowie, The Rolling Stones, Bee Gees and Genesis, the Mellotron swept the music world for about ten years, coinciding with the rise of progressive rock. Then, just as quickly as it emerged, suddenly it became obsolete, its creators throwing the production equipment into the trash. So what was the story behind this enigmatic instrument?

Tale of the tape

The Mellotron was invented in 1963, in Birmingham, England. It evolved from an earlier, American-made instrument called the Chamberlin, an electro-mechanical keyboard that had originally been devised for use in family homes.

In 1962, a Chamberlin sales agent called Bill Fransen brought two of the instruments to England with the hopes of finding someone who could manufacture tape heads for future instruments. He met Frank, Norman, and Les Bradley who owned a tape engineering company, Bradmatic.

Upon seeing the Chamberlin, the Bradley brothers told Fransen they could improve upon the original design. Together with Eric Robinson, who was the conductor and presenter of music for the BBC at the time, as well as television celebrity and magician David Nixon, they formed the company, The Mellotronics.

At the time, Fransen did not mention to the Bradleys that he did not own the patent for the instrument.

The control panel of the M400.

The first orchestral sample library

The idea of the Mellotron was ambitious: to convincingly replace an orchestra. The sounds were created by real strings, flute, organ, and percussion, recording each individual note in isolation.

Such a recording process was unusual for orchestral musicians and they were unable to properly intonate their instruments. In one case, cellist Reginald Kirby allegedly refused to down-tune his cello, so the lower notes were instead played on double bass. According to author Nick Awde, one note on the string setting even contains the sound of a chair being scraped.

The Mellotron operates like a sampler, except that these were the days before digital recording, so all recordings were made on tape. Each key on the instrument is connected to a length of magnetic tape. When a key is pressed, the tape is pushed against a playback head, playing the recorded sound. When the key is released, the tape returns to its original position.

Due to the nature of tape, each time a note is played back, minor fluctuations in pitch – known as “flutter and wow” – occur, as well as variations in amplitude. This means that a note sounds different every time it is played. And really, this is the key to what makes the Mellotron so special.

In 1963, MK I was the first model to be commercially manufactured.

In the above video, you can see Robinson and Nixon demonstrating the use of the Mellotron during its early days.

“I suppose you thought you were listening to a long playing record just then?” remarks Robinson. “Well, you weren’t.”

Afterwards, Nixon describes it as “a musical computer”.

In its early models, the keys of the Mellotron were divided into two halves: lead and rhythm. These were played with right and left hands respectively. The rhythm parts consisted of presets with automatic accompaniments, originally designed for more niche uses, like in a family home, or – as Paul McCartney once mused – in cabarets.

Yet the Mellotron still owed its origins to the Chamberlin. When the Chamberlin’s creator, Harry Chamberlin, eventually found out that his idea was being copied, ill-feeling arose between the two camps. Finally, a deal was struck in 1966 and the two companies agreed to continue manufacturing instruments independently. Bradmatic renamed themselves Streetly Electronics.

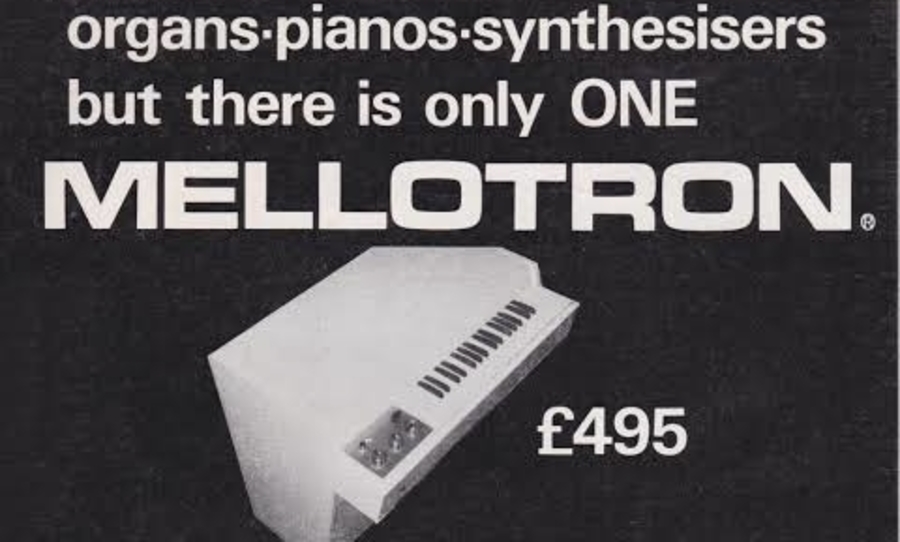

At the time of their invention, Mellotrons were not cheap. They cost around a third of the price of a house, roughly £1,000. They were also heavy (more than 50 kilos), and did not hold up well in the conditions of the smoky, humid clubs in which they were played, or under the heat of stage lights, which caused the tape to stretch or stick.

Due to the primitive nature of the tape mechanism, the instruments were often unpredictable. It was difficult to keep the playback heads in perfect condition and the action of the keyboard was stiff, making it unsuitable for virtuosic playing. Nevertheless, these quirks seemed only to contribute to the instrument’s whimsical character.

Gradually, the Mellotron was embraced. The first rock artist to record with one was influential British musician, Graham Bond, who used it on his hit song Baby Can It Be True. Following Bond, the instrument was used by Manfred Mann, and then Mike Pinder from the Moody Blues.

Early Adopters

The Mellotron was famously adopted by a series of celebrities, including Peter Sellers, King Hussein of Jordan, Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, as well as Princess Margaret, whose husband Lord Snowden reportedly loathed it.

The Mellotron garnered a mixed reception. Holmes noted its “eerie, unearthly sound” whilst The Beatles’ producer, George Martin, described it “as if a Neanderthal piano had impregnated a primitive electronic keyboard.”

Spike Milligan said of the instrument: “If you wanted the sound of marching feet in size ten boots accompanied by Chopin and a portrait of Salvador Dali shaving underwater while whistling ‘The Blue Bells Of Scotland’ this was the machine you had to have.”

By 1967, everyone was experimenting with the Mellotron. According to writer Gordon Reid, the rock world “took the Mellotron to its heart, and it was this that ensured its success.”

Allegedly, it was Pinder who introduced the instrument to John Lennon and Paul McCartney, leading to its use in the 1967 Beatles’ song Strawberry Fields Forever, which author Mark Cunningham describes as “probably the most famous Mellotron figure of all-time.”

The Beatles continued to record with Mellotrons for Magical Mystery Tour (1967) and The Beatles (1968). Later, Paul McCartney also used the instrument in his solo career.

In the late ’60s, Brian Jones used a Mellotron on several songs by The Rolling Stones including We Love You, She’s A Rainbow, 2000 Lightyears From Home, and Jigsaw Puzzle, and in 1967 the Bee Gees used it on Every Christian Lion Hearted Man Will Show You on their third album Bee Gees’ 1st.

A Future in Prog

The instrument found itself in the midst of the burgeoning genre of progressive rock in the United Kingdom and the United States. The scene included psychedelic bands who had abandoned standard pop traditions in favour of new sounds, a fusing of styles, and the use of more poetic lyrics, with the ultimate objective of creating more thoughtful music.

Due to its versatility, bands were able to put the Mellotron to lots of different uses. In 1969, English progressive rock band King Crimson adopted the instrument for its orchestral sound. Whilst in 1972, Genesis used it for block chords to create more of a synth pad presence on their album Foxtrot. In 1969, the Mellotron was played by Rick Wakeman on David Bowie’s hit Space Oddity.

In 1970 the M400 model was released, which contained 35 notes and a removable tape frame. From there on, the instrument was adopted by Tangerine Dream, who used it on albums Atem (1973), Phaedra (1974), Rubycon (1975), Stratosfear (1976), and Encore (1977), whilst in the ’80s it was used by post-punk bands including Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, XTC, and IQ.

Yet, despite its continual use, future prospects for the instrument had already taken a downturn in the ’70s. After a trademark dispute, the Mellotron name was acquired by American company Sound Sales in 1976. From this point on, all Streetly-manufactured instruments were sold under the name Novatron. Sound Sales manufactured their own Mellotron model in the early ’80s, whilst Streetly produced a road-cased version of the M400 in 1981, the T550 Novatron.

Yet by the mid-80s, rapidly developing technologies resulted in both companies suffering great financial losses. This was due to the rising market of synthesisers and solid-state electronic samplers. The digital age was in full swing, and tape had become outdated. The Mellotron, with its unreliable, warping characteristics – the very thing which gave it character – belonged to the past. All of a sudden, the instrument was rendered obsolete.

In 1986, Streetly Electronics folded, and founder Les Bradley threw most of the manufacturing equipment into a skip.

Nevertheless, the instrument continued to be used. In the ’90s, Oasis incorporated it on (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, particularly on hit single Wonderwall, which featured noticeable use of the cello sound. It was also used by Radiohead on several tracks on OK Computer (1997), as well as by Air on Moon Safari (1998) and Virgin Suicides (1999).

Eventually, Streetly Electronics was reinstated by Les Bradley’s son John, as well as Martin Smith, resuming full-time operation. In 2007 they even built a new Mellotron, the M4000, which combined some of the original layout and features with a digital bank selector. Celebrated for its unique character, the legacy of the instrument remains even to this day, where its distinct sound is emulated in numerous plug-ins.

The Mellotron was a perfect mirror to the epoch in which it was born. Emerging at a time of great, flourishing change, it provided a then-modern answer to the technology of the time. And yet, it still managed to remain somewhat untamable, eluding the precision that the digital age would soon bring, even as it existed on the very edge of its dawn.

To this day, the Mellotron remains one of the most unique instruments ever created. And even as the digital world progresses further and further into the future, there is arguably still something special in that “flutter and wow” – a moment never quite the same as the last.