There’s A Meaning Here, But The Meaning Doesn’t Mean A Thing

Shan, Valerie and Zoe are sitting on a deck. It’s hot. Shan is nursing a drink and Val is occupied with her phone. Zoe is rolling another joint.

SHAN: What would you say if I told you….

VAL: Here we go.

ZOE: No, what? Tell me.

SHAN: What if I said The Easybeats, Tame Impala and The Church were all the same? That there was something tying them all together…

VAL: Not this again. Can we –

ZOE: No, I wanna know.

VAL: Okay.

SHAN: Well like I’ve said, they’re connected. There’s something there, something which pulls them all into a singular moment.

ZOE: I’d probably tell you –

SHAN: Wait! Before you jump to any conclusions, I’d like to share a few of my thoughts.

VAL: Well if you are going to explain it, explain it right.

SHAN: I’ll try. So picture this. An 11-year-old is sitting at home. His dad and stepmother are fighting again. He’s teaching himself the drums.

VAL: No. This needs to start further back, way further back.

SHAN: Okay. Steve Kilbey is leaning back in an armchair. He’s dazed on opium, wondering if he’ll ever have another hit.

VAL: Oh God, you must be high! Further.

SHAN: Five figures huddle around a mixing desk. They’re sixteen thousand miles from home.

VAL: Okay now we’re getting somewhere.

ZOE: What year is it?

SHAN: 1967.

ZOE: The ‘60s!

SHAN: It’s the Summer of Love. Culture is awash with distorted colours and opened minds. A powerful and strange music is taking sway. Rock has undergone a shift. What started as a teen sensation feels like a revolutionary force. Lyrics are heady and recordings are ambitiously complex. Albums have become experimental playgrounds – vehicles for personal and cosmic truth.

VAL: You’re romanticising.

SHAN: Am I? People really felt this way, and wouldn’t you? Broadcasting from San Francisco and Swinging London – rock, pop, folk, blues, jazz, country, avant-garde and raga were all blending into one. Songs were harbouring drug allusions and musicians found themselves in a rare and temporary situation where art and commerce were complementary. Are you following?

ZOE: Sure. Continue.

SHAN: All these young people are getting around the idea that musicians are doing something more than just making music. And they are, they’re travelling beyond the aesthetic to become prophets and public personae. Exalted figures.

VAL: They were all on drugs.

SHAN: So were a lot of artists throughout history, but never quite like this. A new strain of popular music was striving to capture the effects of drug use and other transcendent moments. With music as a centralising force, trippy ideas were spreading across film, photography, poetry, theatre, fashion, design, visual art and even literature.

VAL: You’re babbling.

SHAN: I’m not! I’m just trying to get across that music was the glue binding this whole operation together. Not only that, but it was opening its listeners to something more.

VAL: Here it comes!

SHAN: Many called it psychedelia. And unmistakably it was a movement, a series of images, sounds and events reducible to a time and place. From 1965 to ‘67 it burned white hot. Yet no sooner than did it reach its peak it disappeared, collapsing under the weight of the hopes and dreams of those it had ensnared.

ZOE: So we’re talking about psychedelic rock, right? What exactly is ‘psychedelic rock’ anyway?

SHAN: At the time they actually called it acid rock.

VAL: Which was?

SHAN: It’s hard to explain.

VAL: If Zoe is going to put up with your nonsense, could you at least give her an example?

SHAN: For some it’s a style, a combination of musical elements. But many artists themselves are at a loss to explain. Maybe it’s always been here, a sense or a feeling – a thing gestating from long before as a holdover from ancient shamanism or something older than humankind itself. Something alien from the outside. A dark mass beyond the perimeters of understanding, an irrevocable changer of what is known. A kind of otherworldly sensation beyond words but relatable between any two minds who have experienced it!

ZOE: Could you pass the chop bowl?

SHAN: Sure. So yeah, it’s a feeling! A surrealism, a transcendence, a nostalgia for something lost, dead or dying. A step beyond the rational aspects of the physical, psychic or spiritual minds – a code for profound experience. Jimi Hendrix once called it “Sky Church Music”.

ZOE: Hendrix? Right on!

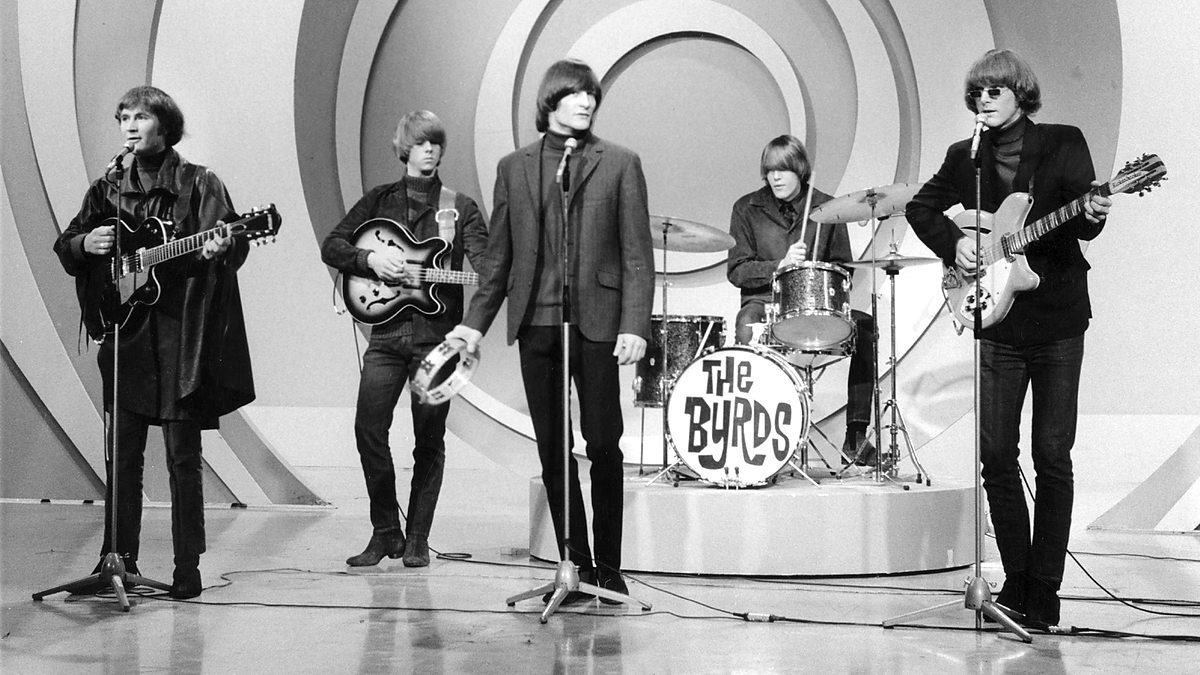

VAL: Regardless of where it came from, I think what Shan is trying to say is that it caught on. By the middle of the ‘60s, it began attaching itself to music. The Byrds’ 8 Miles High is often held up as the arrival of the psychedelic sound but it was also carrying in the music of the Yardbirds and The 13th Floor Elevators. It was practically hanging of off the lyrics of Bob Dylan’s Tambourine Man, and that was from the year before. The Gamblers’ single LSD 25 was even hinting at it as far back as in 1960. Did you know that people have been tripping on LSD since 1943?

SHAN: Hey! Who’s telling the story here?

VAL: Just a little context.

ZOE: I didn’t know you were so into this, Val. But Shan, aren’t those first three bands you mentioned – The Easybeats, The Church and Tame Impala – all Australian? How did psychedelia get down here?

SHAN: Val might disagree, but I think for most people it came via The Beatles.

VAL: No, I agree. Even before psychedelia, The Beatles were kind of a national obsession. Somewhere between being booked to tour Australia in ‘63 and touching down in Sydney in ‘64 they absolutely blew up.

SHAN: That’s it. Their Australian tour left a powerful impression. Not just on their fans but on local artists too. Overnight surf and rock ‘n’ roll were out. Musicians began growing their hair and writing their own songs.

VAL: There’s a good documentary you can watch about that tour. What’s it called?

SHAN: Doesn’t matter. The thing you have to understand is that The Beatles were always changing, faster than almost anyone could keep up with. As they went on their songwriting began showing more and more maturity and sophistication. Then, after being turned on to pot by Dylan, they then started diving into LSD and tapping into all these other countercultural undercurrents. After being exposed they recorded Rubber Soul in 1965.

VAL: They were kind of psychedelic at this point, I think. I’ve heard someone describe Rubber Soul as psychedelia hiding in plain sight.

SHAN: True, but with Rain in 1966 they weren’t hiding from anyone. Rain announced their arrival to psychedelia. Later that year Revolver embraced this new aesthetic entirely and by the time Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band rolled out the following year, they’d achieved total mastery of the form.

ZOE: Weren’t we talking about The Easybeats?

SHAN: I may have gotten a little ahead of myself, but it’s all relative. Everything The Beatles did was feeding back into The Easybeats. Heaps of Australian acts were following what The Beatles were doing, but none more intently than The Easybeats. They were observing them at every step. They formed in wake of the Fab Four’s ’64 tour.

VAL: Did you know that they were all migrants?

SHAN: They were, right! A bunch of misfits to be sure but they were sharp. After forming in a Sydney hostel, they were quick to switch on to the new possibilities The Beatles offered. Powered by Stevie Wright and George Young they rapidly rose to become of Australia’s biggest domestic act.

ZOE: Young? Wasn’t he one of the guys from AC/DC?

SHAN: Hold on, I’ll get to that. Remember, we’re still only in 1967 here. Seeing that The Beatles had advanced into full-blown psychedelia, The Easys were keen to follow. The group had done well in Australia but to take it further they’d relocated to the UK.

VAL: Which was a big deal back then!

SHAN: Totally. And it seemed to be working for them. In London, they were riding a high. Friday On My Mind and a few other earlier singles were kicking up a fair bit of interest in England and even the US.

ZOE: I know that one. “Monday I’ve got Friday on my mind!” How’s that for a Golden Oldie?

SHAN: Hey, it still goes okay! Anyway, the group were determined to make their own voyage into psychedelia. In 1967 they entered this experimental phase. They were smoking a ton of hash and taking a fair bit of LSD.

VAL: It kinda paid off too didn’t it?

SHAN: It did! They had some success with a song called Heaven and Hell. But despite all their confidence, the songs that followed – Peculiar Hole in the Sky, She Said, and My Old Man’s a Groovy Old Man – couldn’t sustain their success. When fifth record Vigil stiffed in mid ’68 and that was about it for them. Fresh out of money and a little dispirited, the group returned to Australia in ’69 and split not long after.

ZOE: Were there other psychedelic Australian bands?

SHAN: You bet! Have you ever heard of The Masters Apprentices? They were making a name for themselves around this time with a single called Living in a Child’s Dream. The Twilights were another big act. They cut the concept album Once Upon a Twilight in 1968.

VAL: Don’t forget The Bee Gees. I mean they were born in England but came to Australia when they were kids.

ZOE: “Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin’ alive!”

SHAN: Don’t remind me.

VAL: Actually, Shan you might have liked them. At this point, The Bee Gees sounded more like The Beatles. Also, I think there’s one song you’re forgetting.

SHAN: The Real Thing! Tailing in at the end of this all was an unknown artist named Russell Morris. Now get this, his producer was Molly Meldrum. This was before Countdown, so think of him here as more of a behind-the-scenes music industry kind of guy. He had a few plates spinning but one of those was producing Morris who he thought he could make The Next Big Thing. So much so that he sank $10,000 (the budget for two or three entire Australian albums at the time) into recording Morris’ debut single.

VAL: Most of it wasn’t even his money. The record label must have been having kittens!

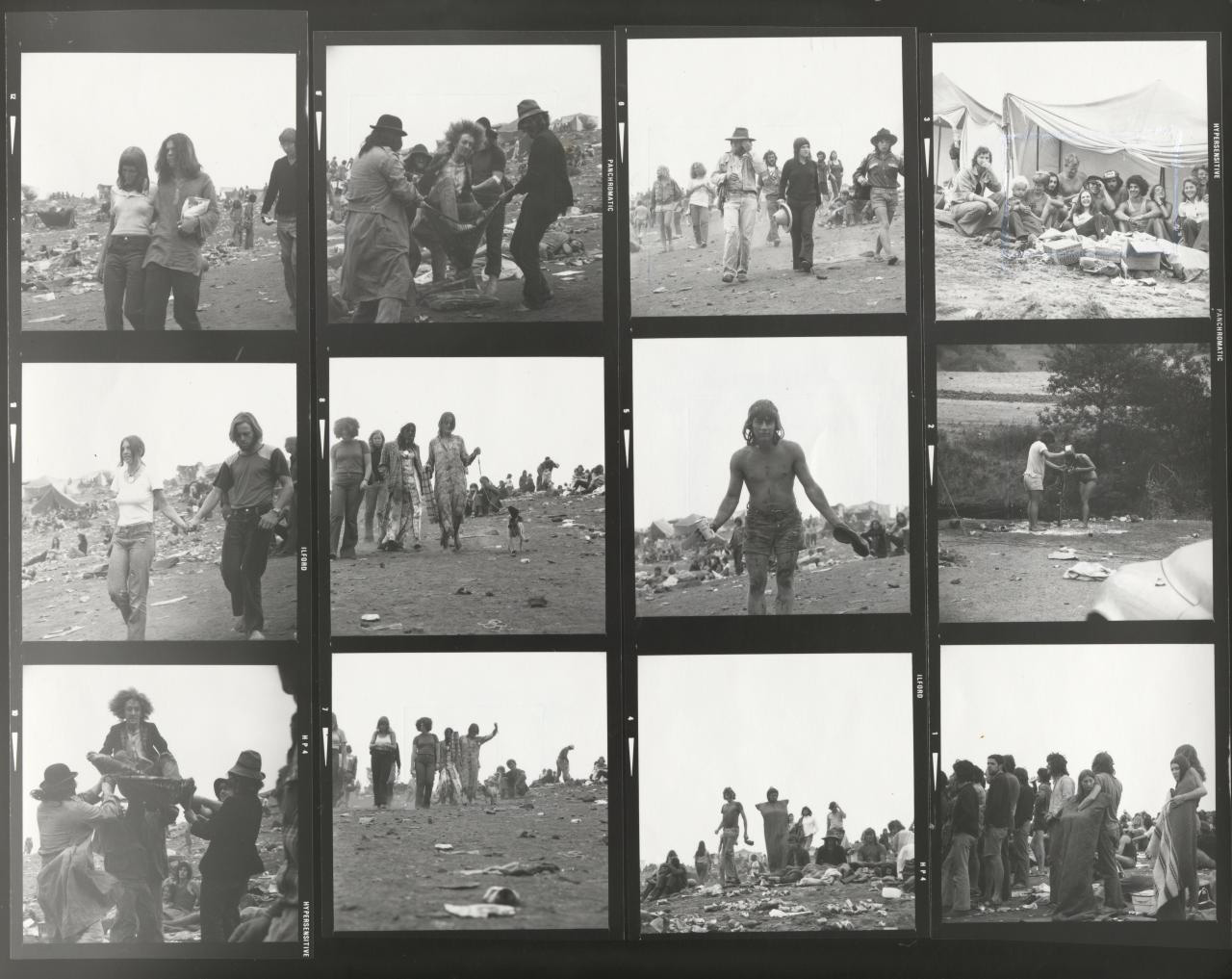

SHAN: No doubt they were, but it paid off. The Real Thing was a hit single in 1969. Anyway, this was the initial peak. By the end of the ‘60s this whole generation who had dropped acid and grown their hair out were now drifting apart. They had thought that they could change the world, but the violence of The Rolling Stones’ free festival Altamont and the Manson murders in the US shattered a lot of those dreams. The whole movement had been really grassroots but within a couple of years, a host of organisations and individuals had found ways of monetising the lifestyle these kids and hippies had preached. Peace and love succumbed to hip capitalism. The breadheads won.

VAL: There was kind of a hippy backlash too. Not just from the authorities but artists as well. After all the drugs, innovation and endless changes, a lot of American and English bands were looking to ground themselves and reconnect with who they were. Kaftans and Flower Power were out. Australians followed suit.

SHAN: George Young certainly did. He’d paid his lip service to psychedelia, but it had never really been his thing. Using a lot of the connections he’d made during his tenure with The Easybeats, he pursued his own dream of writing and producing hit records with another ex-Easybeat Harry Vanda. George also used some of this pull within the industry to kickstart his brothers Angus and Malcolm’s band. So there’s that AC/DC connection you were asking about.

ZOE: Ah! I see.

VAL: George had done well for himself. But not everyone was so well accommodated by the changing times. Not long after The Easybeats folded, their singer Stevie Wright began drifting into a lifetime of poverty and heroin addiction. For many, the ‘70s were a difficult time.

SHAN: You think so? Because I would say that for many Australians, those airy ‘60s sentiments continued to litter the new decade. Where could The Masters Apprentices have drawn the lyrics to It’s Because I Love You if not from the hippy dream? And surely something was still circling throughout the air at Sunbury, Australia’s own belated Woodstock moment!

VAL: Hmmmm.

SHAN: What I’m trying to say is that those psychedelic vapours were still swirling. They certainly were when a young Steve Kilbey bought a TEAC tape deck in 1977 and started making weird home recording experiments. And I’d say they were definitely lingering when he quit his job in the public service to pursue music, and later still when he formed The Church.

ZOE: The Church? I’d forgotten we were even talking about them.

SHAN: Real funny. The Church, they came together in Sydney in 1980. They were a new kind of Australian band, one preaching their own kind of autonomy. Kilbey was inspired by the flash of David Bowie and T.Rex.

VAL: A glam rock kid! I always thought he was a little…

SHAN: Easy! So there was that glam influence but the same time, he and the band wanted to return to the past. They wanted to continue where Dylan, The Beatles, Hendrix and The Byrds had left off.

VAL: Which was a lofty kind of idealism if you think about it. The hippy hangover was far from over!

SHAN: They struggled. After courting with some early overseas success, the group found themselves at odds with the prevailing trends of the 1980s. They donned paisley, picked up six-string guitars and disarranged their minds with psychedelic drugs. Their music was a rare melding of moody extravagance and populist instinct. When that finally all came together, they recorded their greatest hit.

VAL: Which was?

SHAN: You’ve got me on that one. Uh…

ZOE: Under The Milky Way?

VAL: How would they say that on the radio? “The atmospheric lead single from fifth album, 1988’s Starfish.”

SHAN: I knew that. It might have been a throwaway remark, but Kilbey once said that every song he ever wrote he owed to pot.

VAL: The man loves his weed!

SHAN: Well in his view it allows his mind to do the things it wants to do – ‘free association’ I think he calls it. But yeah, he does love his weed. Bongs, pipes, chillums, vaporisers, Chronic, Maui Wowie, White Widow, Northern Lights – you name it he’s done it all. A genuine connoisseur!

VAL: Sounds like somebody I know.

ZOE: Well, I am done rolling this spliff…

SHAN: Well hey then, why not share it around?

[All partake]

SHAN: A funny thing about Steve is that he hates psych rock. He described it as “acid mixed with bad speed”.

VAL: The Church always were a little slower burning. They’ve been playing music longer than The Grateful Dead!

ZOE: Stupid question. Were there other bands in the ‘80s too?

SHAN: Totally. The Church weren’t alone. Many artists below the radar found refuge in the music and idealism of the past. Underground, psychedelia was enjoying a widespread resurgence. Quite independently of one another, clusters of revivalists sprang up across the world. It was happening in Australia too, there were acts like The Stems, The Moffs and a number of others centred around a Sydney label called Citadel Records. Then you had acts like The Moles bridged the ‘80s through to the ‘90s where a new generation was turning on.

ZOE: Such as?

SHAN: Well the influence wasn’t as obvious, but I think there’s a case good that acts like You Am I were slightly touched by the psychedelic. Then in the 2000s came Wolfmother and The Vines. But really, they were incubators. Something far bigger was coming.

VAL: “Something’s trynna get out and it’s never been closer.”

ZOE: Tame Impala! Love it!

SHAN: Fast forward to 2007. A shy and underconfident dropout – and let’s face it a bit of a stoner – begins uploading his music online. A little anxious that it won’t get off the ground if people find out that he’s written and recorded it all himself, he spins the idea that his bedroom recording project is actually a band called Tame Impala.

VAL: Well, he was playing in bands. They had a live setup.

SHAN: What I’m trying to get at is that there was psychedelia in Kevin Parker’s sound. He had an interest in The Beach Boys inherited from his father Jerry. It was Jerry who had helped him learn guitar in the first place and in whose home studio Kev conducted his first recording experiments on a pair of tape decks. He had a pretty rough family life mind you, his parents separated when he was four.

VAL: If families didn’t break apart, there’d be no need for art.

SHAN: It left an impression and as a result, he was kind of a naughty kid. He’d been smoking pot since he was 11.

ZOE: Can you pass those papers?

SHAN: Sure. So here was this kid who was shoplifting, getting high and vandalising other people’s property. He wasn’t a happy camper. But I mean put yourself in his shoes in 2009. Here is this guy from Perth, the most isolated city on earth, who’s now attracting fans and record labels alike. He links up with Modular and records the first Tame Impala album, which I’m sure you both know is called Innerspeaker.

VAL: While he was putting the record together his father Jerry died from cancer.

ZOE: Oh fuck.

VAL: I mean he even sings about it on Lonerism – The Sun Is Coming Up.

SHAN: Lonerism! That second album was huge. It’s one of my favourites too. There’s all this experimentation – he’s rewriting the rules of psychedelia! I mean I get the impression that Kevin’s always been kind of a solitary guy but here he’s not only looking really deeply inward but also coming out of his shell a little. Alongside Innerspeaker it pointed this whole new generation to the possibilities of the psychedelic sound. It feels like that in 2012 the word ‘psych’ re-entered the vocabulary of every Australian under 25. At the same time Tame was lighting the fire for a thousand other bands.

VAL: I remember. It was just the coolest thing in the world for a while there wasn’t it? Everyone wanted to be psychedelic.

SHAN: And it kept getting bigger from there. Kevin returned for third album Currents. It was a blockbuster. But if you ever meet him, maybe don’t drop the p-word.

ZOE: Come again?

SHAN: Psychedelic. Don’t tell him his music is psychedelic. He gets it a lot in interviews and while he’s often shared that he’s had all these really drugged out psychedelic experiences when people ask him about his own music, he denies that it’s all that really psychedelic. What he says instead is that he’s just trying to make music and put his feelings into something which moves people. I mean, I can agree with that. Can’t you?

VAL: This is going to sound a little pretentious, but I’m going to say it. He doesn’t want to be hemmed in. If you put him on the spot, he’d say Tame Impala is just as much pop, disco, funk as it is psychedelic. Then again, what he plays is often the opposite of what he says.

SHAN: But Zoe, can you see what I’m saying? Through psychedelia these artists are connected.

VAL: There are more Australian groups too which you haven’t mentioned.

SHAN: Like Gong? Steve Kilbey’s non-Church projects too. Did you know he has a brother who made music as The Crystal Set?

VAL: You didn’t know Under The Milky Way but you knew that?

SHAN: Gimme a break. Also, there’s The James Taylor Move who released the country’s first taste of psychedelia with Magic Eyes. Kanguru, Rainbow Generator as well as Radio Birdman figure into the ‘70s side of the story but they’d take a little explaining. Plus, in ‘88 you have this explosion of acid house which kickstarts the Second Summer of Love. Not to mention Flying Nun and Dunedin sound, sure it happened over the pond but when did we stop claiming New Zealand’s talent as our own?

VAL: Any more, Socrates?

SHAN: Tyrnaround, the Lipstick Killers’ Hindu Gods (of Love), The Scientists are from the ‘80s. The Hoodoo Gurus wore paisley shirts, does that count?

VAL: You haven’t gotten into the sociology of Gizzheads or even mentioned Mink Mussel Creek plus that whole mad mosaic of Perth outfits. Beaches, Stonefield, Babe Rainbow ditto.

SHAN: I could go on, but I’m feeling a little high. The point of it all is that here in Australia there’s a psychedelic pulse. I don’t think it’s something which ever stopped. The bands are separate, each floating in a different space and time, never quite overlapping but all have touched with this dark unknowable energy and set that experience to sound. And, not to get on a high horse here, but more than fifty years since psychedelia first erupted it continues to awaken people’s imaginations. That is, if it didn’t come from somewhere long before.

VAL: What a long strange trip it’s been.

SHAN: And really, that’s about it. So tell me, Zoe. What do you think?

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 10. Grab your copy here.