That jarring two-note intro to Purple Haze, the unholy riff in Black Sabbath‘s Black Sabbath, the opening to the Simpsons’ Halloween Specials. What do these songs have in common? They’re all based around a little thing called a tritone. You might have heard it called ‘the devil’s note’ or ‘the devil’s interval’ or maybe even ‘diabolus in musica’ if you’re a Slayer fan.

Think for a moment what these songs actually sound like.

The words ominous, anticipating and unsettling might come to mind, that’s because of something classical musos call dissonance. The tritone is a musical ratio between two notes, which has been employed throughout music’s history to convey moods that require something a little more sinister. For a simple interval, the tritone has gained a dark reputation for invoking the spirit world and conveying the messages of evil. But how much of this is just musical folklore or metalhead myth?

The tritone is restless, dissonant and foreboding, but is it really evil? Maybe that’s something you’ll have to decide that for yourself.

The Blasphemous Theory

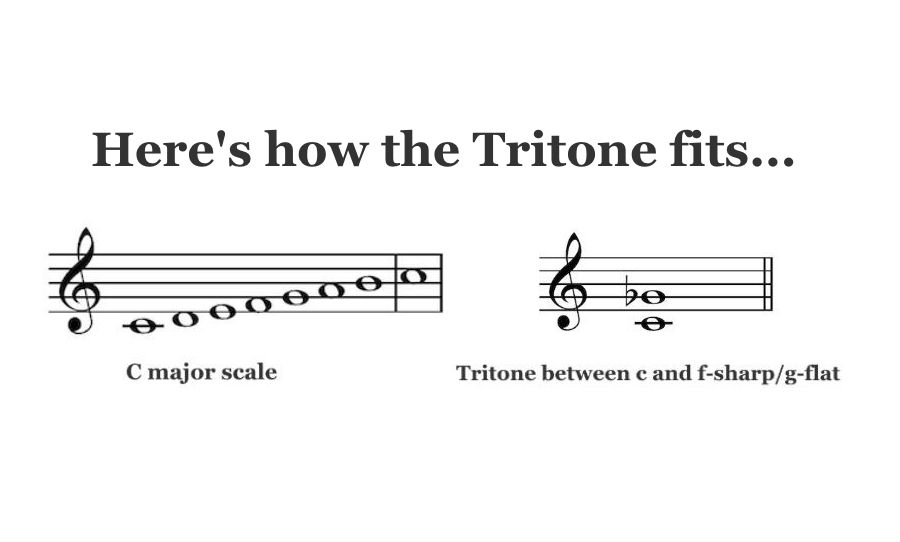

As mentioned, the tritone is simply an interval between two notes, formed from 3 whole-tone steps. So for a practical example C to D, is one whole step, D to E, is the second and E to F sharp is the third whole step, so the tritone lies between C and F-sharp. The two notes create a tension that begs for resolve, such as another chord with more pleasing intervals to release the tension. For this reason, the tritone is sometimes described as ‘dependent’.

The interval sits somewhere between a perfect fourth and a perfect fifth and is therefore also called an augmented fourth (with a sharp) or diminished fifth (with a flat) depending on context. In more mathematical terms a perfect fifth is 3:2, a fourth is 4:3, while the tritone is a much more complex √2:1.

On paper, it really doesn’t sound too sound evil, unless theory bores the hell out of you, but when played with the right minor scale you can get some really spooky stuff happening. If you’ve got a guitar hanging around, try this (if you don’t, then just skip this paragraph I guess).

Start with hitting the low E string on the 8th fret, the root C, now hit the 10th fret of the A string, that’s the 5th, in this case, a G. Two frets up from this is F, the fourth, all sounds pretty normal, so far but bear with me. Now play the root again and then hit the note between those two, the F# on the 9th fret of the A string. How’s that?… Sounds a little uneasy now doesn’t it. Now bring the D string on the 10th fret into the ensemble and try a chord with the low C, F# and C (if you’ve got distortion hit it).

You’re playing the devil in music and could be summoning occult spirits, so please stop. And if you think it sounds a little scary, don’t fear, you’re not the first to think so.

A Hideous History

If you have a metalhead friend you might have heard them say something like this: “Yeah man, back in Medieval days the Catholic Church outlawed it because they thought it was evil and if you got busted playing it they would cut off your head. Brutal right?.” Well, that’s what mine says anyway.

A little dig on the internet, however, will unveil that perhaps that’s a bit of an exaggeration. It may not have been banned, but it’s widely believed that the tritone was definitely discouraged, at least in Medieval Europe (it should be noted, however, that dissonant intervals have existed in other cultures for millennia without the blink of an eyelid or raising of a brow).

Songs in those days were largely written to praise the lord and to be sung by choirs and congregations. The interval is known to be particularly difficult to sing; they are some pretty jagged notes. Even if you were a monk with chops like Adele, why would you want to sing a dreary sounding song during mass, especially to an audience expecting nice harmonious hymns?

That being said, there actually are a few rare examples of tritones from that time, from monks who were probably considered a little bit rebellious. An example is Dum Sigillum Summi Patris by Pérotin, a famed medieval composer. This particular track contains many tritones, so it’s going to be quite brutal. Try giving it a spin if you think you can handle it.

Fast forward a few hundred years, when a particularly strange German myth entered the public consciousness. Based on the life of the 16th-century alchemist, Johann Faust, the curious tale tells of a highly successful man who was not entirely satisfied with his life. In order to gain otherworldly knowledge, he sold his soul to the devil.

You might have heard of similar transactions. This concept has come to been known as ‘Faustian’ and was probably just an interesting adage created to warn people of ambitious excess. However, as the Renaissance period began to bloom, the story became an inspiration for a new breed of ambitious composers.

The period also brought advances in theory and notation, which were enforced by the Catholic Church to allow ideas to be taught and followed more accurately. Music that was a little more ‘out there’ or hard to play could still be followed by musicians, assuming they had received the right training and read the same notation.

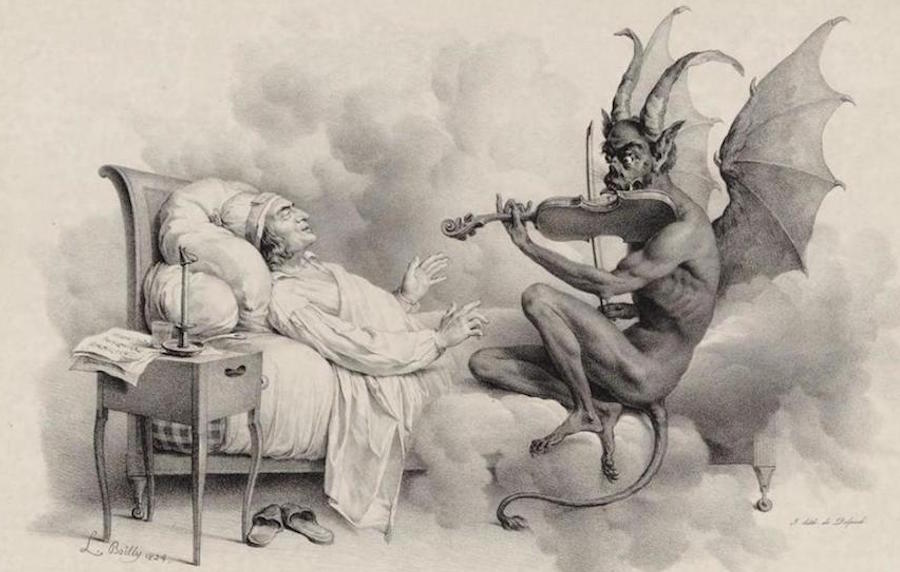

So basically an odd ratio like the tritone could be understood by all, especially during an age where more and more composers were willing to experiment with new or strange ideas. The baroque composer Guiseppie Tartini is famed for cementing the Faustian legend in music. He claimed the devil appeared to him in a “dream” and kindly played him a beautiful violin sonata.

Tartini made a pact for his soul in return for some tantalising otherworldly knowledge. He recounted the incident in French writer Jérôme Lalande’s book, Voyage d’un François en Italie:

“One night, in the year 1713 I dreamed I had made a pact with the devil for my soul. Everything went as I wished: my new servant anticipated my every desire. Among other things, I gave him my violin to see if he could play. How great was my astonishment on hearing a sonata so wonderful and so beautiful, played with such great art and intelligence, as I had never even conceived in my boldest flights of fantasy.”

“I felt enraptured, transported, enchanted: my breath failed me, and I awoke. I immediately grasped my violin in order to retain, in part at least, the impression of my dream. In vain! The music which I at this time composed is indeed the best that I ever wrote, and I still call it the “Devil’s Trill”, but the difference between it and that which so moved me is so great that I would have destroyed my instrument and have said farewell to music forever if it had been possible for me to live without the enjoyment it affords me.”

The violin sonata that Tartini scribbled down, formed the now classic Devils Sonata or The Devil’s Trill Sonata, and yes, it contains many tritones. Tartini actually advocated the use of a specifically tuned tritone called the lesser septimal tritone which is tuned lower to the ratio of 7:5, and sounds slightly more resolved.

This particular piece is most likely where the tritone began its descent into darkness.

So if Tartini started the tritone’s hellish mythos, where then did its name come from?

Diabolus in Musica was a term applied to sinister sounding intervals since at least the 18th century although, as Denis Arnold, states in his New Oxford Companion to Music, the term was probably established far back in the Middle Ages. Despite this, the term likely referenced many dissonant tones and was probably just a very old-school way of telling your friend their mixtape sucked.

Johann Joseph Fux, was one of the first to link the term to the tritone, who cited the phrase in his 1725 work Gradus ad Parnassum. The ratio was said to be ‘mi against far’, yes the same ‘mi’ and ‘far’ from The Sound of Music.

Regardless of who coined the term, the legend was set, and compositions surrounding the mythology became more and more commonplace. 19th-century composers studied and obsessed over the ratio and tried to outdo each with their sinister compositions. Franz Liszt was one of the culprits, who created a series of Faustian waltzes in which he claimed to have “wielded the diabolos in musica himself.” I must say the opening to the Dante Sonata is particularly bleak.

You can’t help but think, had these musos been born a couple of centuries later that they would be diehard metalheads.

A Curse at the Crossroads

A couple of hundred years down the track, tritones and devilry gained a new platform through the mythology of the blues. You may have heard the folk-legend of a young Robert Johnson, who in his youth had a strange chance encounter whilst living on a plantation in rural Mississippi. He apparently met the devil by his local crossroads at midnight, and according to legend, the devil asked to tune his guitar, to which Johnson said something like, “sure, why not, Lucifer.”

Proposing a generous trade, the devil offered to give Johnson mastery of the instrument in return for his soul. Faust would be proud. Johnson sang of the incident in his 1936 song Cross Road Blues, which has become a classic blues number, immortalised by generations of blues legends like Cream and wedding singers such as John Mayer.

In this regard, the blues has always carried a hint of occult folklore, however, blues music is intrinsically tied to tritones via the ‘blue note’. Part of the blues scale, the note is related directly to the same lesser septimal tritone that Tartini advocated. Blues progressions are built on dominant 7th chords, which contain a tritone between the 3rd degree and the lowered 7th degree, which doesn’t actually get resolved in the same way that it would in a classical composition. For this reason, the tritone makes the blues sound restless and gives it the feeling of movement or moodiness that is all too familiar.

It probably should be mentioned that as music started to get a little heavier, another bluesman by the name of Jimi Hendrix, exploited the virtues of the tritone. 1967’s Purple Haze is a case example; the jarring two note lick of the intro almost sounds like a call to the spirit world.

Also in the late 1960s a few young boys from Birmingham, UK, picked up on the interesting properties of the tritone ratio.

Making Metal

On their 1970 self-titled debut album, Black Sabbath incorporated a tritone in the main riff of their also self-titled track Black Sabbath. It was a hook that would change the way heavy music developed for years to come and set the mood for the metal genre as a whole, particularly subgenres leaning to the side of doom. The initiative is credited to guitarist Tony Iommi, who despite not receiving classical training, heard a certain phrase in a classical piece that he just had to borrow.

The story goes that during a no doubt civilised evening in, Iommi and Sabbath bassist Geezer Butler enjoyed a classical piece by Gustav Holst titled, Mars, The Bringer of War from the 1914, Planets Suite. Iommi was so inspired by the mood of the tense orchestra that he picked up his guitar and began playing along to Holt’s epic.

He landed on a few notes, including the godforsaken tritone and conjured a rolling riff, apparently inspired by a dream he endured of a slowly walking dark figure – it definitely sounds fitting. Black Sabbath went on to use the tritone in many of their songs. Their follow up album, 1970’s Paranoid, employed faster approaches to the sound, heard on the likes of War Pigs and Paranoid.

As the 1970s progressed, the ratio came to be widely adopted by many heavier acts. Five years post In The Court of the Crimson King, King Crimson’s 1974 song Red used a garish tritone, accompanied with a key change interlude, I guess it was the years of prog rock. Bands like Rush, Judas Preist and Iron Maiden took it to another level, with quick heavy riffs that would become a staple for some of the metal world’s darkest heroes.

Metallica, Slipknot, Slayer – you couldn’t name a metal band who hasn’t dabbled with the devil. In fact, guess what Slayer’s 8th studio album was called… Yea, Diabolos in Musica, it’s practically a tribute album.

So it’s Surely Pure Evil Then?

There’s no question that the tritone has stirred up its fair share of shit. A bit of a hell-raiser you might say. It’s been the foster child for the experimental, the deviant and those working on the darker end of the musical spectrum. But to call it evil would shortsighted.

The simple fact is, human ears prefer harmonies; which technically are simple ratios that are easy to digest and understand. Ears just find it harder to reconcile with complicated fractions, and that’s fine, maths isn’t for everyone.

Still, context plays a big part in the tritone’s role, its tendency to arouse alertness has even given it employment in police sirens. Its relationship with the occult is a pretty Western phenomenon and as mentioned, in Eastern scales the ratio is seen as far more normative, and that’s because they emphasise resolve.

So it doesn’t always have to feel evil then. When the dependent sounding ratio is resolved appropriately the mood is closer to one of mischief or anticipation. Artists from Busta Rhymes to the Strokes have incorporated tritones, all without being accused of occultism. Maria from West Side Story, it uses a big old tritone. That’s probably as far from evil as you can get.

But what about probably the most famous tritone of them all? Danny Elfman’s The Simpsons Theme. Well, I’ll just leave this here for you to decide.