The likelihood is that there isn’t a soul alive on this earth who hasn’t fantasised about fucking a fictional character. But Sonic the Hedgehog pornography? Yes friend, and that’s just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

The internet has an age-old adage that is often referred to as Rule 34. Where it comes from no one is entirely sure, but its elegant insight far outstrips the mystery of its origins. But what does Rule 34 mean exactly? Essentially, the fnf rule 34 states that if something can be conceived of, then there is porn of it on the Internet.

My first reaction to the fnf 34 rule was to nod along as my brain tried to crack holes in its central premise; I know there’s a lot of porn out there, but I felt confident in my imagination’s ability to come up with some fresh perversion that was entirely my own. The further down the rabbit hole I went the less sure I became, and eventually I was left with little option but to ponder the apparent accuracy of Rule 34.

Not only had my imagination been outrun by the brain trust of the internet, people had already diligently gone about realising it through text, drawings, videos and Rule 34 pictures online.

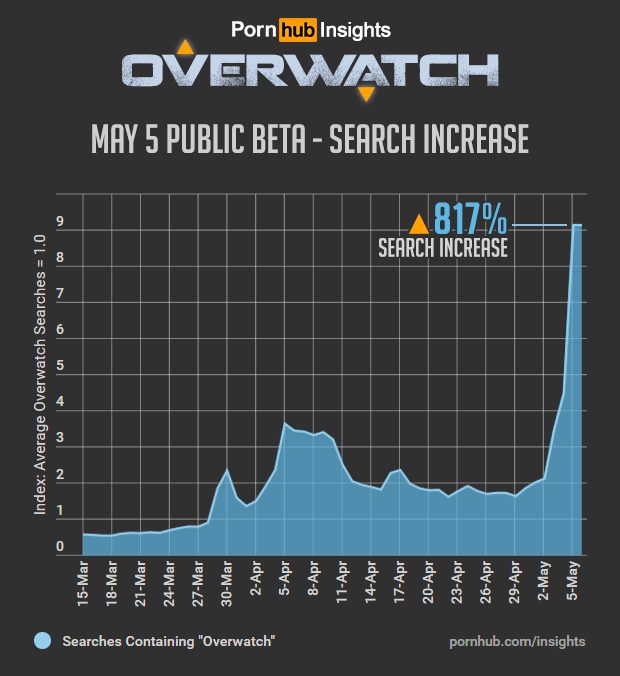

I found mainstream porn parodies of everything from The Simpsons to Marvel’s Avengers. I skulked through the recesses of Reddit and bore witness to Sonic the Hedgehog’s monstrous cock penetrating anything and everything in its path. And before I was even late for dinner I skimmed through Pornhub’s trending videos and realised Overwatch, cosplay, and dildos have great synchronicity.

Still, a question refused to vacate my shell-shocked mind… why the Sonic the Hedgehog rule 34 inclusion? The skill, effort, and creativity behind much of this work is immediately apparent, but the underlying rationale left me confused. In hindsight, I think I was too fixated on what the material isn’t (at least to me), rather than what it is.

fortnite rule 34???😭😭 pic.twitter.com/vKcsbGFuzP

— omarr (@omarrwrld) February 20, 2022

Pornography the Brave

To understand why a certain kind of pornography exists, it is first rather important to understand pornography in a historical context. In this pursuit I was fortunate enough to be able to call on University of Technology Sydney Professor Alan McKee, whose expertise on sexuality, media, and pornography proved extremely helpful.

In our conversation, Professor McKee was quick to point out that pornographers have been at the forefront of almost all communication technology innovation, at least insofar as they relate to entertainment.

“Every drive to engage with new communications technologies, from the invention of the camera in the 19th century onwards, has been driven by making porn. The early adopters for home movies and VCRs, for computers and the internet, were driven in every case by an interest in making and consuming porn.”

It only makes sense then that this pioneering attitude has persevered as the internet has grown wildly vast (yet increasingly divided and compartmentalised). As new communication platforms emerge, so too does our ancient appetite for sexual expression and discovery.

But I didn’t start this journey because I was puzzled by the prevalence of pornography; it makes perfect sense that the first humans to etch drawings into stone quickly turned their gaze to what happens when the lights go out. The answer I was searching for needed to go some ways in explaining why someone on the internet is sharing images of Nintendo’s Kirby being used as a Fleshlight proxy (yep).

And the answer, as Professor McKee highlighted in our conversation, is intermingled with our understanding of what constitutes entertainment.

“Entertainment is always about spectacle, it’s about showing you things you have never seen before. It’s about showing you things that are interesting, strange, and niche. Freakshows are a key part of 19th century entertainment and that logic continues, not to just Cirque du Solei, but also to modern pornography.”

Spectacle is the single most important component of entertainment. Without it we are left with stale art that lacks sufficient motivation to attract any sort of mainstream audience. However, that which constitutes spectacle is a somewhat subjective matter, which is why our taste in entertainment varies so much from person to person.

The defining characteristic of spectacle, as opposed to say pleasure, is that it’s something you haven’t seen before. A spectacle isn’t necessarily desirable, but it should come close to forcing a response from its audience. What type of response though will depend on each individual’s proclivities, as well as what they have or haven’t already been exposed to.

Take the example of kissing, pretty tame right? Not necessarily. Contextual factors such as who is kissing who, or where and when the kissing is taking place, can drastically alter how the event is perceived. Obviously our relationship with and understanding of those performing the act is also highly relevant.

So while your parents sharing a snog in the comfort of their home will hardly be of much interest to anyone bar them, the Queen of England trading spit with Kanye West in the Vatican could produce the 100 year storm scientists have been warning us about. The devil’s in the details, and the same is true when it comes to spectacle.

Princess Peach in the auditorium with tentacles

Fan culture is incredibly intertwined with the concept of active consumption of media. What is meant by this is that fans, once characterised as the mindless masses, are in fact extremely engaged with their chosen mediums. They search their favourite texts for hidden meanings, contemplate alternate theories, and focus on the bits they find most compelling.

“Our very understanding of who fans are is people who make dirty pictures and dirty stories.”

And unsurprisingly, this is often sex. As long as fan fiction has existed, aspiring writers and fans have explored the sexual ‘what ifs’ of their favourite works. This is particularly true of works which shy away from the sexuality of their characters (like cartoons, child-friendly programs, or many video games); possibly because it means authors have a blank canvas on which to project, possibly because it seems more taboo.

Either way, these sorts of works are likely to elicit strong responses from audiences because they place characters in circumstances that are alien to our understanding of them. As Professor McKee succinctly put it, part of the thrill of pornography is “watching things go into places that you know they shouldn’t go”, and this edict extends past the obvious into the narrative of the pornography.

What narrative you ask? I probably needn’t say more than beginning, middle, and end – or start and finish. Sex has an inherent narrative structure to it, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s so satisfying to watch. And if pornography manages to introduce an extra element of spectacles in the ways we’ve discussed, then it’s likely to be pretty compelling.

Now, in regards to our seemingly bizarre obsession with fictional characters, it isn’t actually all that surprising when viewed through this framework.

It isn’t so much that we are turned on by the thought of a fictional character having sex, although that’s perfectly possible, it’s that it’s novel to us. We are witnessing something exist that appears to be contradictory or foreign to our prior understanding of it. We are watching rules be broken, and revelation tearing down the curtains.

We are watching Princess Peach in outer space with a tentacle monster. And by all accounts, that is a rather spectacular thing. Spectacular enough, at least, that it’s hard to look away.

I think my favorite thing i’ve done in my Youtube career was when I put a 2 minute clip of me and the boys reacting to live action Mario porn directly after an ad read where they forced me censor the word “ass”. I had no intention of using that clip but I was feeling very petty

— Matt (@ItsBlarg) February 17, 2022

But is it also spectacularly wrong? It’s difficult not to hypothesise about the kind of person who would be interested in consuming or creating Rule 34 Sonic material. Similarly, drawing a causal line between it and various societal issues such as antisocial behaviour or pedophilia is somewhat tempting; cartoons and video games are associated, rightly or wrongly, with children after all.

However, to do so would be dangerous and grossly unfair. Humans tend to search for evil, or its point of conception, in places they don’t see themselves. Which is why niche interest groups and minorities are so often vilified – frequently for things that have little to do with them. It is seductive to blame the Other for that which we don’t understand because it allows us to gloss over our own ignorance. Unfortunately, it rarely leads us to the actual culprit.

When asked about this sort of armchair philosophising Professor McKee simply remarked:

“People enjoy all kinds of pornography, a whole range of things for different reasons at different times, and there is nothing innately pathological about enjoying cartoon images of people having sex.”

And on closer inspection, I’m convinced that the answer to our original question lies at the heart of that assertion. Because at the centre of our most bizarre desires is a reminder that we are all essentially searching for the same thing: something that excites our interest and makes us feel alive – something spectacular.

It just so happens that spectacle, like beauty, is vastly diverse.