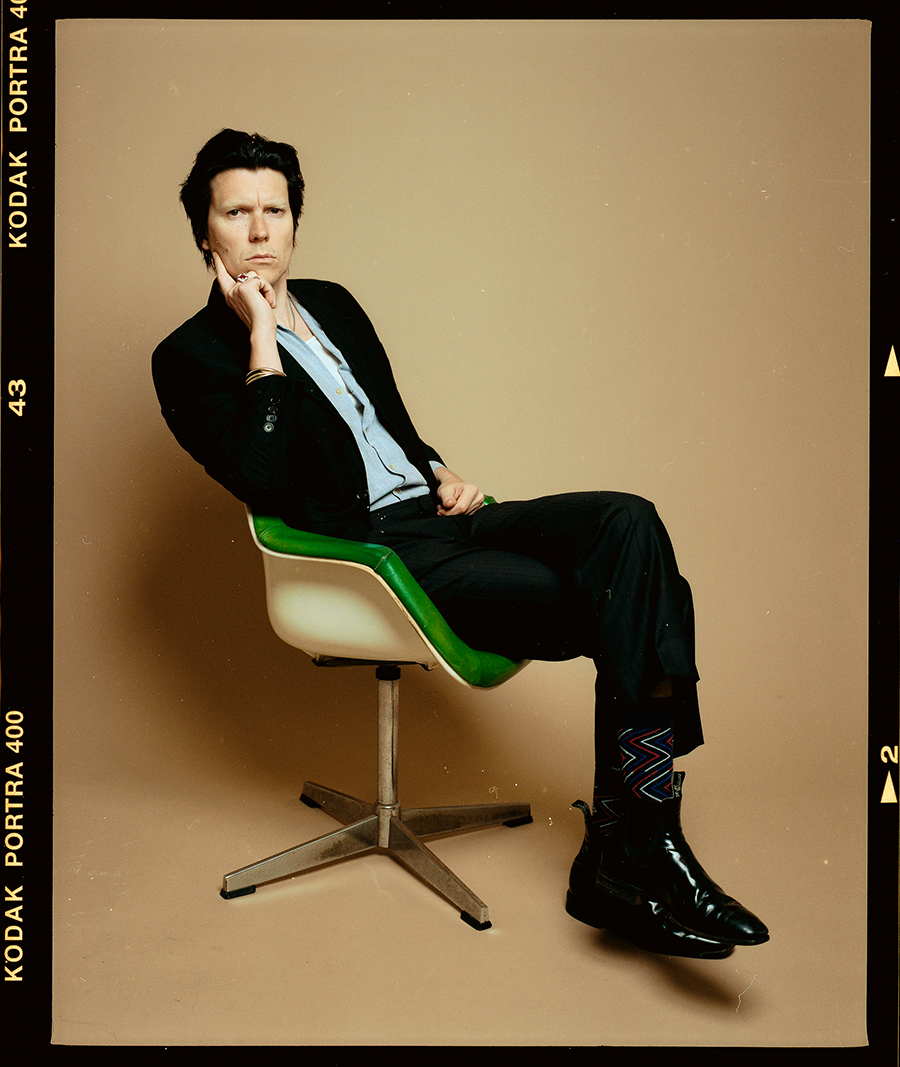

Whether he’s the hero or the villain, a love-torn crooner or a spokesperson for the seedy, you can’t doubt that Alex Cameron has many, many interesting things to say.

Sleazy businessman, chatroom sex pest, step-dad, and head-over-heels lover. These are all parts Alex Cameron has played, using his music as a tool to explore microcosms of human behaviour. Not everyone gets it and often, listeners will merge Cameron and his creative subjects into one. He’s willing to be the “poster boy” for these stories nonetheless.

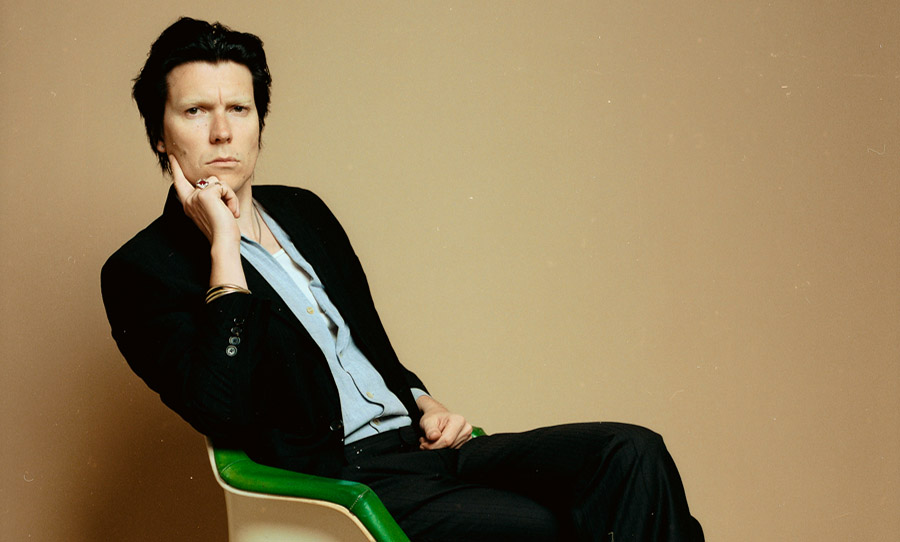

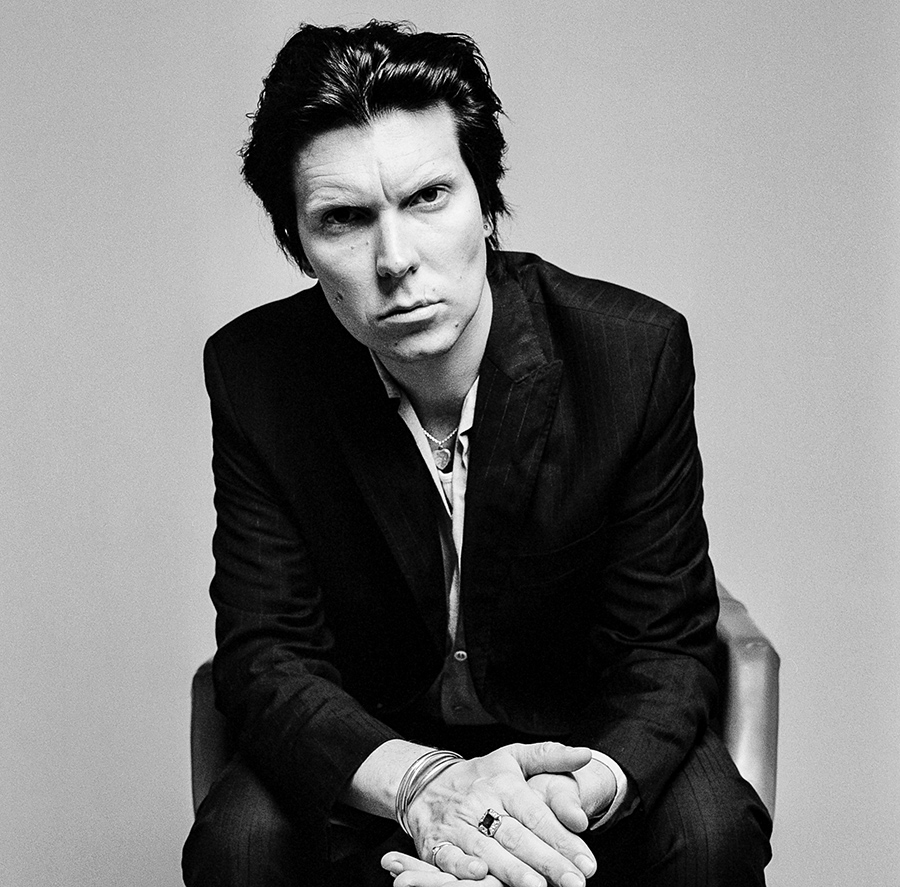

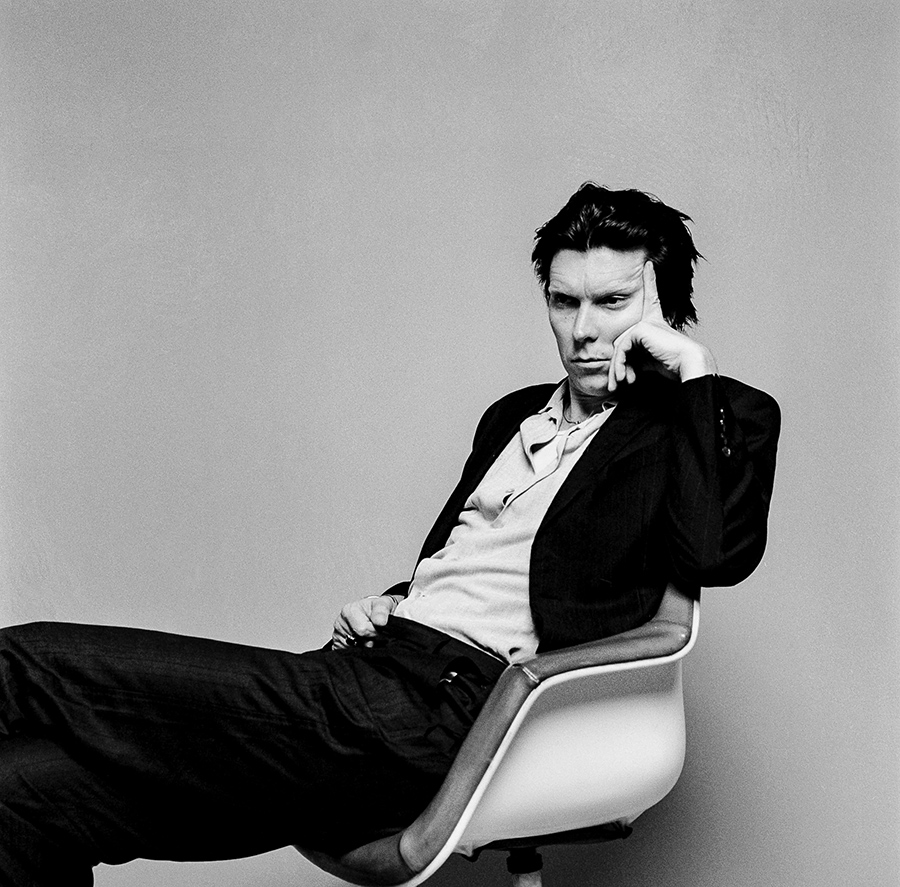

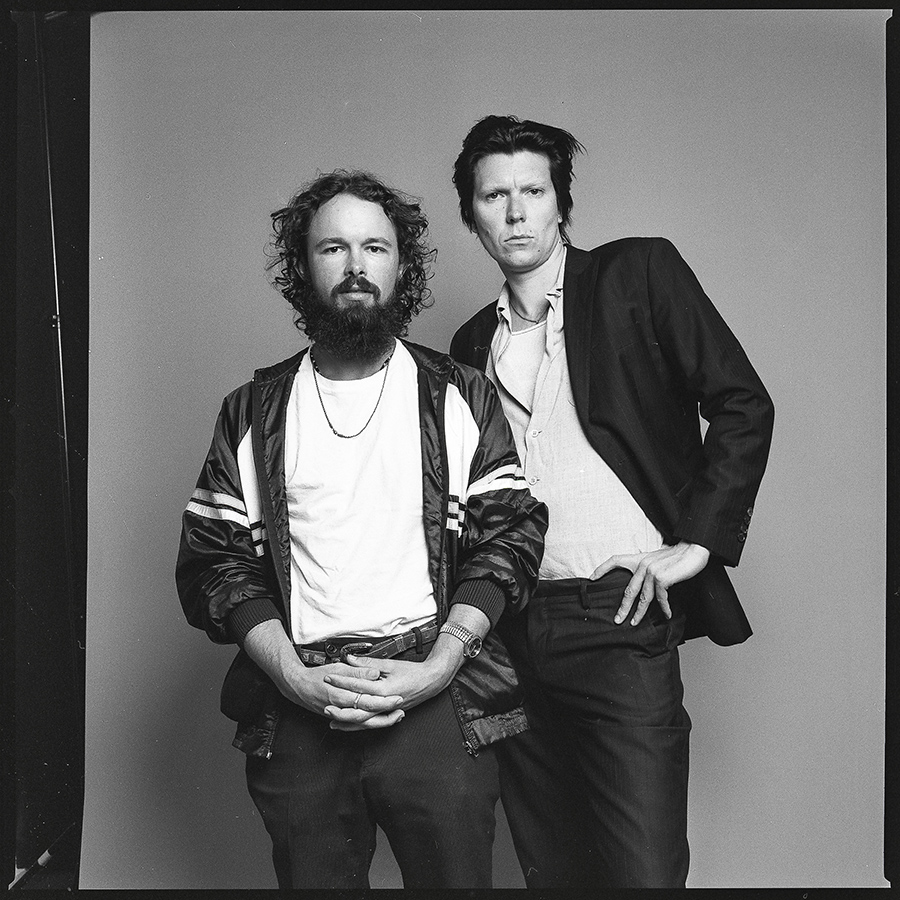

It makes him an exceptionally interesting person to discuss his art with – you’re able to tap into so many stories at once. When Sydney was far less locked down than it is currently, we took some photos and then that’s exactly what we did.

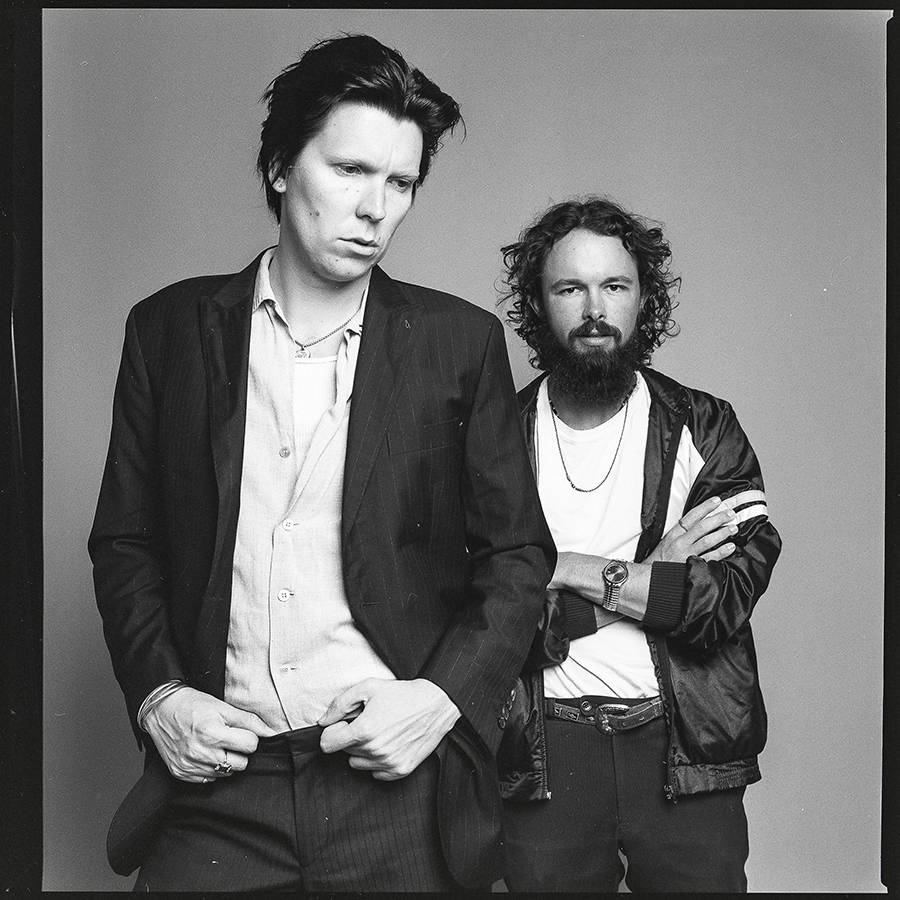

While his business associate Roy Molloy sat idly by, perched like a hawk for the occasional interjection, Cameron and I delved into the places his songwriting has been and where it may be going next.

HAPPY: I was in a record store just this week and my roommate Jackson, without knowing anything about you, picked Forced Witness off the shelf based off the record sleeve. As someone whose primary trade is in sound, how does a situation like that – where someone’s first impression is entirely visual – make you feel?

ALEX: Good, yeah. I think just yesterday we were with Jason from Sleaford Mods and he said the same thing, he was just on his computer and he saw the album cover for Miami Memory and he started listening to it. I think it’s gratifying because we put a lot of effort into the visual side of things, you know? Whether it’s Michael Bailey-Gates taking the Miami Memory photo or Jemima Kirke designing the artwork, or Britt Mccamey doing the photograph for Forced Witness, or Mclean Stephenson doing the cover for Jumping The Shark… it’s not by chance that we’re working with them, you know? These people have been chosen because they’re artists and we know that they can deliver something dynamic. So it’s a collaboration, a meeting of ideas, we take our covers and our artwork very seriously.

HAPPY: Is there a narrative arc to your record covers? It’s early days of course, but the last two in particular I can see as being part of a series.

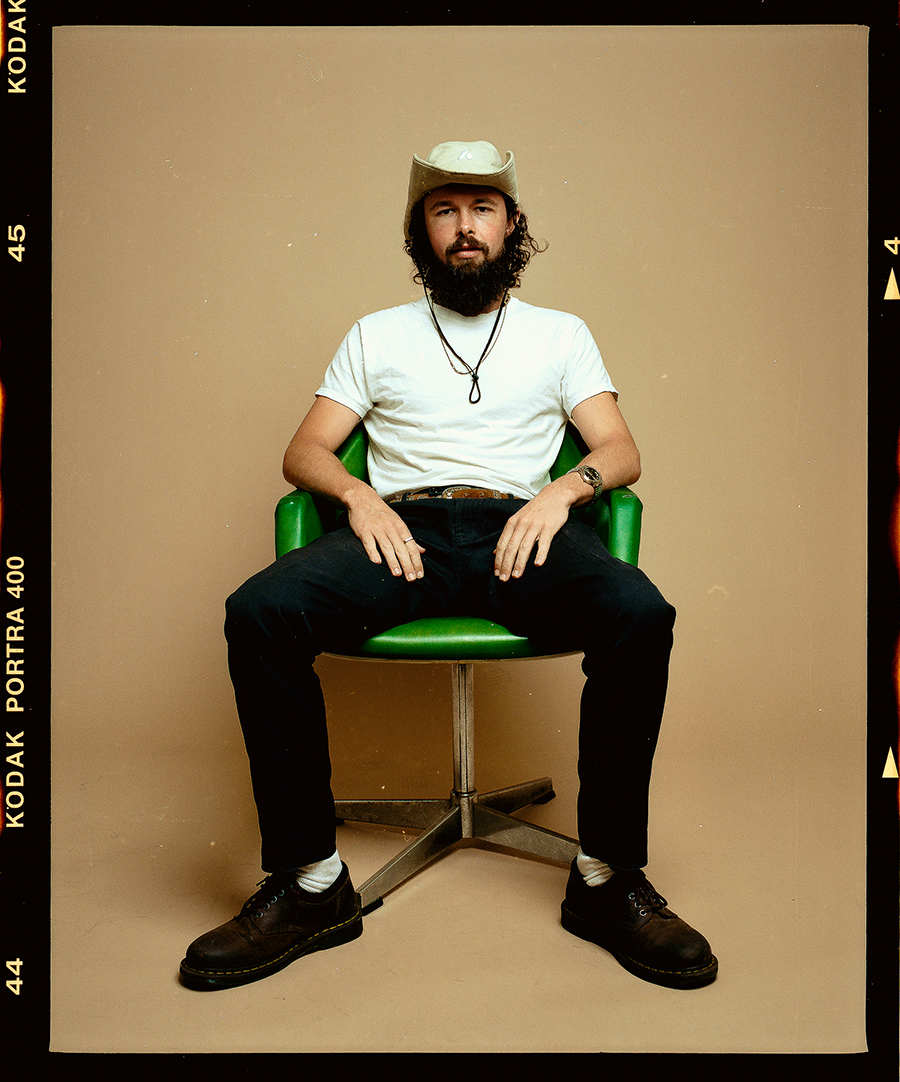

ALEX: All three of them are just photographs, as a project. I like the idea of covers being quite robust portraits of whoever I feel like at the moment. I think there’s certainly… it’s a way of me presenting how I think I should appear when I’m singing at the time. And you can’t do that every night on stage, we don’t take makeup or wigs on the road, but ideally that’s what I’d look like on the stage.

HAPPY: Do you think musicians can separate themselves from the way they look any more?

ALEX: If as an artist I was focused more on the visual side of things, we’d have more resources and a completely different message, I think. If we have had more resources. But if I decide to bleach my eyebrows and dye my hair because of where I am, I have to live with that every day. If I had the resources I could just do it, pop it on. I actually had this idea of growing my hair and making my own wig out of my own hair, and then I could just shave my head. Zero maintenance, put the wig on. I looked up how much it cost to get a wig made of your own hair… it’s a huge price tag.

ROY: You need three times as much hair to make the wig.

HAPPY: How do you know that?

ALEX: Because we’ve looked into it! You have to bind the hair, it’s a huge process. And then I thought if I was growing my hair that long to make a wig, I’d like to donate it.

HAPPY: On separating yourself from the way you look… other mediums of art – novelists, poets, cinematographers, architects – they’re in a situation where what they make exists a little more on its own. Are you envious of that at all?

ALEX: No, I don’t really. We’ve been quite fortunate with the way our music has been received, because there’s certainly been instances where people find it challenging to step into a fictional world. For instance, say if one of our songs were in a movie, it would be very easy to consume and digest. With music we’re trained to really expect something deeply personal and somewhat infatuating. But ultimately, you know, that’s such a small percentage of people who’ve heard our music that respond in a way that’s either confused or maybe… what’s the word? You know, we’re working hard, we play shows, we play to audiences that are getting bigger and bigger, and there’s no need for us to make something visual. Although it would be fun to make a movie or a TV show, producing a visual like that. For now we have an audience that are willing to come along for the ride with us, and I’m willing to represent the songs. The poster boy of our music.

HAPPY: The other side of that, separating yourself from the music, can be dangerous.

ALEX: I think that music and sound are so underrated when it comes to… you know, movies and films. Half of these iconic scenes wouldn’t be as impactful if it wasn’t for the music that’s in the soundtrack. I find that music’s so manipulative. The idea of distancing myself from the songs… I think it’s stronger to represent them.

HAPPY: There’s this pivotal moment for your audience, which is the moment you stopped writing songs as other characters and began writing songs as yourself. If you had to pin that down to a specific event or moment or motivation, when did that happen and why?

ALEX: Probably it was… I’m always trying to develop and improve, and there was a moment when we were living in Queens, New York. I guess I always really wanted to write love songs but they always felt like they were a little bit too easy to do, you know? In terms of all the imagery is there, all of the cliches that are there have been taken. I didn’t know that I had anything to add to it, but as I started to fall deeper and deeper in love with my girlfriend, I noticed that there were a lot of areas that I felt had been under-explored in the love song. Instead of having to manufacture something I could just let it happen naturally. The challenge with Miami Memory was not getting in the way of it, just letting things flow naturally, not being an obstacle. That was the learning process that I had to go through, because normally I’m constantly… you know if a song is like a rat in a maze, the other records have felt like I’m designing the maze as the rat is crawling and I have to put little blockers up to get in its way, to sort of train it and control it. But this, Miami Memory is very much letting the rat free from the maze.

ROY: I would have said hamster.

ALEX: Hamster. Of course.

HAPPY: That’s interesting. Other people I’ve spoken to who aren’t necessarily character-driven, but definitely won’t represent their songs as you do… in the early stages it’s perhaps a confidence thing, or the awareness that they didn’t have the technical knowledge to write something that was representative of themselves. Maybe there’s a degree of fear to it. But it sounds like the opposite for you.

HAPPY: Yeah, I think so. I think songwriting is more like discovery as opposed to creation. I feel like all these songs have always been there, I’m just trying to find them. If you put me in a courtroom and someone was trying to sue me, I’d be like “no, I wrote that fucking song,” but on a theoretical level the way I view any song that we’ve got on a record… on paper sure I’ve got writing credits, but I do feel as though every song already exists. Given that on a technical level they’re all just combinations.

HAPPY: There were two musicians [Damien Riehl and Noah Rubin] who developed an algorithm that generated every 8-note, 12-beat melody combo that could possibly exist. They released it to public domain as an artistic statement; ‘everything already exists, here’s every melody.’

ALEX: Right, it’s interesting! I think that internet and copyright is still very much the Wild West and I don’t think anybody knows what’s going on. I think everyone’s just hoping that the old system is going to hold, but I don’t think it will.

ROY: I think the whole thing was set up to protect Disney, and now a whole bunch of musicians are scrapping over a couple of thousand dollars here and there.

ALEX: The Mickey Mouse law, huh?

HAPPY: Something I couldn’t find clarification on, and this is going way back to Seekae and The Worry. Was that you writing? Was that character-driven, or was that a combination of yourself, John [Hassel], and George [Nicholas]?

ALEX: I think everyone had a bit of writing on that one, but if I was writing lyrics on that record I was doing character stuff. Definitely. It was all fiction stuff. But back then the songwriting was… that was a learning process, it was such early days for me, and I think it would be hard to take credit or even speak about these songs now.

HAPPY: Well speaking of looking back, I often encounter two schools of thought. The ‘no look back’ mentality where everything new is better and shinier, but then there’s the idea that there was something special about earlier – less burdened I guess – art. What’s your opinion on the importance or unimportance of older work?

ALEX: As in my older work, or older work generally?

HAPPY: Yours?

ALEX: I suppose I view my work as being a snapshot in time, of a certain point in time. So old music is about as important to me as an old photo album. It is important, but only to look back and see what was going on. I don’t necessarily think it informs me going forward, it’s just nice to reflect upon.

HAPPY: How about you, Roy?

ROY: I like the photo analogy. A lot of songs wind up being nice memories, but in terms of how important it is… I’m sure we could have all gone along without it. People writing songs even 20 years ago didn’t have access to the history of music like we do now, and we manage to crank out songs ok. So I don’t know about importance.

HAPPY: I like that analogy too. Music can be that for fans as well – a few years ago I rediscovered a 30GB iPod video that was a perfect snapshot of my 2008 music taste.

ALEX: Wow! And it still had all the music on it?

HAPPY: It did, it still had the old charger which I had lying around. It still worked.

ALEX: What was on there?

HAPPY: Red Hot Chili Peppers, Green Day… but as I was scrolling through I realised that I’d forgotten about so many albums.

ALEX: Yeah, I wish I’d taken more care to backup my things. I just don’t have anything, I don’t have any photos, it’s all gone.

ROY: I lost that laptop five years ago. I’d had that for so long.

ALEX: Did it get stolen out of the car?

ROY: Yeah, it was boosted in the same robbery.

HAPPY: I think something has been lost in digital world, I think it’s why people are buying physical again… because they want to remember the things that are important to them.

ALEX: That’s the thing, I think photography is having its moment again because people are wanting tangible, physical memories of things.

HAPPY: To finish, then. It’s been more than a year since Miami Memory was released and presumably, much much longer since you wrote the songs. How has your focus shifted since that album?

ALEX: I’m still focused on performing songs, I’m still really enjoying singing them and playing with Roy and the band, but I am already focusing on the next record and I’m already writing the songs. I think I’ve kind of scratched an itch in terms of writing about myself and I think I have other things that I want to explore again. It’s a little Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, I suppose. Some moments I want to sing about something personal but a lot of the time I’m really quite tempted by these characters and monsters and villains, just the darker, more lonely territory that ultimately comes from a place inside myself. I do like to observe and comment. I have a feeling I’ll go back to doing that.

HAPPY: Villains inspire you more than heroes?

ROY: I don’t think an action movie works without a good villain. The power of the villain is to dictate the state of play.

ALEX: That’s true… can you just say I said that?