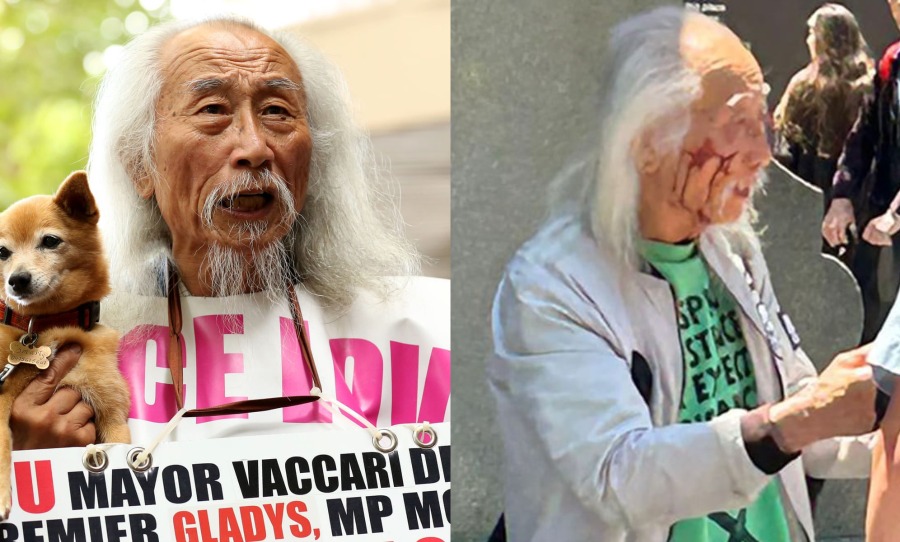

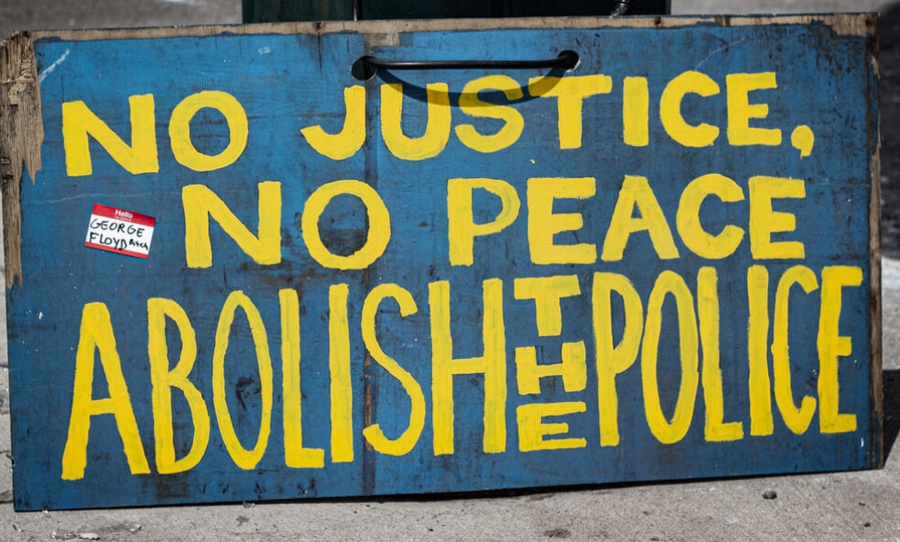

None of us have missed the recent uproar of voices arising from the Black Lives Matter movement, originating in America following the death of George Floyd at the hands of police officers. The movement has well and truly taken flight here in Australia too, with organised protests erupting throughout the nation amid a global pandemic.

Police brutality and excessive use of force against minority groups has been at the forefront of global criticism, with many people calling on a defunding or abolition of the force in order to truly heal the relationship between the community and police.

So, can healing Australia’s mistrust of police authorities begin with a rework of policies and laws resulting from the abolition movement? What is the abolition movement exactly and what kind of change does it entail in our community? Is it really something that would have a profound and lasting impact that would be enough to encourage our First Nations communities to feel safe and protected by the enforcers of the law?

We had a look into all of your questions and more, gaining some insight from key players in this socio-political movement; a policewoman on the frontline and a woman of colour who feels unsafe when confronted by the people who are meant to protect us.

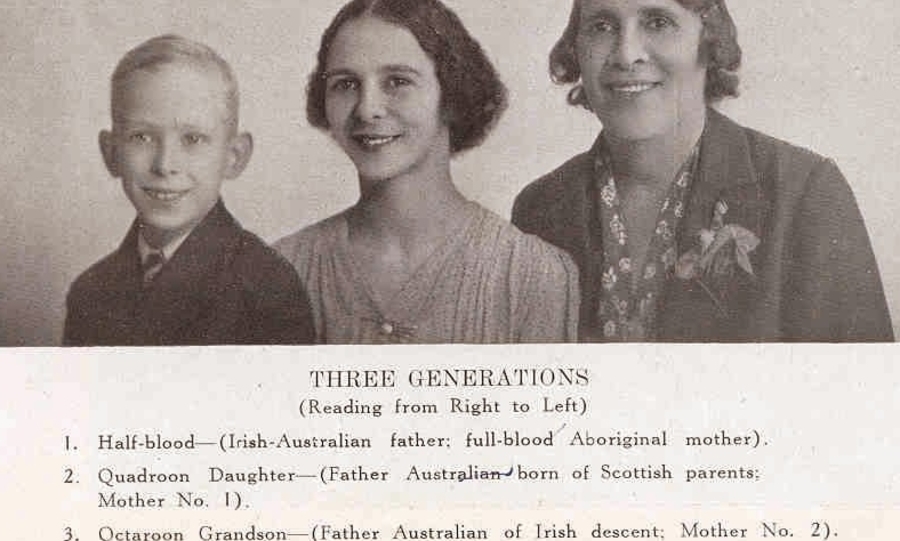

Let’s break it down for you. We all know why the abolition movement has come about in the face of police brutality against minority groups – in particular, people of colour. This is nothing new, the government and police have been responsible for segregation and paternalism since colonisation first went down. Assimilation Policy anyone?

So are we really surprised that this has bred into our current society, where prejudice is rampant amongst police authorities and people of colour are wary of placing their trust in the system? Isabella Dunphy, a woman of colour who currently lives in Sydney city, gave us insight into her experiences:

“Growing up in Waterloo – which has an amazing Indigenous community – you would see the mistreatment often. Individuals would be questioned in a hostile manner, often leading to an aggressive physical outcome instigated by the police.”

“I know of two girls, who I will keep anonymous, that have not reported a rape which they endured both at the ages of 14. They believed the police force wouldn’t take action, solely because they’re Indigenous Australians.”

Many will automatically jump to the conclusion that these situations occur due to the prejudiced, racist attitudes that police authorities exemplify, upheld by systems that foster such actions. But how about the perspective on the other side?

An inner west policewoman and detective gave us her point of view, we’ll call her Alice for the purpose of keeping her responses anonymous:

“I know the NSW Police Force is genuinely invested in ensuring all officers engage in their duties without bias, and I know they are genuinely invested in ensuring all officers are given the knowledge and skills to be culturally sensitive when engaging with our Indigenous population.”

ONE bad apple spoils the bunch. And yall got SEVERAL at EVERY precinct. what if I told you the Tree they came from was used to lynch folks?

— Chance The Rapper (@chancetherapper) June 2, 2020

I asked Alice to explain how she knows that this is being delivered within the force.

“I know this because, like all my colleagues, I attend the training, I see the posters in the halls, I talk to our Aboriginal Community Liaison Officer. And I talk to my colleagues, the vast majority of whom I know do this most difficult and personally damaging of jobs because they are good people who genuinely want to help others.”

“But they are a reflection of the society from which they come. And I firmly believe that the changes that need to happen to increase the trust our Indigenous people have for the police has to largely come from outside the NSWPF. And it’s a slow process.”

Is it fair that the police have copped the brunt of criticism recently, are they simply a symptom of the racist and discriminatory values embedded in our larger society? Alice says this isn’t completely true, but agrees it is the major reason for the disproportionate targeting of people of colour and Indigenous Australians in this country:

“I am not naive enough to think that policing biases are not one of the reasons that there is a massively disproportionate amount of Indigenous Australians in custody. But I am hopeful that if society can change, so too will any biases that exist within the police.”

And the facts don’t lie, while Indigenous people represent only three per cent of Australia’s overall population, they make up more than 27 per cent of our adult prison population and 55 per cent of the youth detention population.

Over 424 Aboriginal people have lost theirs lives since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

That’s 14 people murdered a year.

If a white person was murdered every month for 24 years by the same group, we’d call them terrorists.

You call it Australia.

— Nakkiah Lui (@nakkiahlui) June 2, 2020

Like much of Australia, Indigenous filmmaker Iven Sen is disturbed by these statistics:

“Because of all the social problems around Indigenous people, they [police] spend all their time locking blackfellas up. So when they come to them for help, there’s a reluctance. It’s like, ‘Don’t come to me asking for help, I’m trying to find your brother to throw him in jail’.”

Abolition of the police would see a reallocation of funding within the police force to community-driven initiatives based on a model of prevention rather than intervention. And no, the abolition movement doesn’t mean that police would suddenly cease to exist. Rather, it is a gradual process in which strategic reallocation of funding would shift the responsibility more heavily from the police authorities onto community members and tailored providers of support.

Accountability would be placed upon those who are most familiar with the community they live in, rather than the police who are patrolling with guns or tasers in hand – who most likely don’t inhabit the community they are reprimanding.

This would create an opportunity for increased funding and resources for more mental health services, anti-violence programs and social housing redevelopments – just to name a few avenues for investment. There is a more police-friendly concept to describe this process: ‘justice reinvestment’. Ultimately, the police abolition movement – or justice reinvestment – coincides with demands for self-determination and autonomy by people of colour in this country, and it begins with community control over decision making.

Watch this incredibly powerful monologue from Meyne Wyatt on racism. Change starts with all of us.https://t.co/SYaqzy02Cw

— Indigenous Literacy Foundation (@IndigenousLF) June 9, 2020

And it is entirely possible. Bourke is a regional community in New South Wales who had the highest rate of juvenile conviction and crime in the entire state – until a drastic justice reinvestment project saw the power removed from the police and redirected to the community. The results are astounding. Just five years since The Maranguka Project was introduced, rates of criminal offences have fallen dramatically:

- 18% for major offences

- 34% for non-domestic violence related assaults

- 39% for domestic violence related assaults

- 39% for drug offences

- 35% for driving offences

And it seems the underlying contributor is acknowledging that people in the community are the experts of their own experiences and have the best knowledge of what works to tackle high rates of crime. Along with that comes a healing between residents and police officers – the project required police officers to volunteer in the process and Indigenous community leaders have commented on the improved relationship and collaboration between people of colour and police authorities.

Isabella agrees with this objective:

“A world in which Indigenous Australians and people of colour feel protected would start with more Indigenous run stations and facilities available. Our current system is based on the laws which left Indigenous Australians behind…”

She takes a moment.

“Over the years, the police force has proven to profile Indigenous Australians, and I think we need more Indigenous people in higher power to cater to their needs. It’s so far beyond earning trust back.”

“Bottom line, there needs to be a complete change, and I believe our communities would benefit from abolishing the police.”

Make sure you are following these key social media accounts that empower and elevate Black voices:

Words by Claire Adema

Header: ‘A Symbol of Pain and Frustration’ by Scott Marsh. Buy the design on a tee here, with all proceeds going to charity.