Eliza Reilly’s Sheilas is a history book, but not like the ones you read in school. There’s a laugh on every page as she pays tribute to the overlooked female icons of our past.

Let’s face it — conventional history books are a goddamned sausagefest. Eliza Reilly, comedian and storyteller extraordinaire seeks to address this state of affairs in Sheilas: Badass Women of Australian History (Pan Macmillan).

Laid out in chronological episodes, she digs deep into the colonial past and works her way toward the present, unearthing stories that are absurdly comedic — on the surface, at least. If you read between the lines though, a thought-provoking line of questioning emerges: why was it so easy to condemn women to the forgotten backwaters of history? Why was the morality of women always in question? And why would you put an egg in your wine?

We asked Eliza to tell us about these legendary, history-changing sheilas, and why we still have so much to learn from their stories.

HAPPY: When you define what a Sheila is you say “being a Sheila has nothing to do with being ‘good’,” and “Simply put: you don’t learn the big lessons in life only from the ‘good’.” What does that tell us about how women have been depicted in the history books?

ELIZA: I was interested in exploring these other women of Australian history because the female-identifying, big Australian icons that we all know and cherish — like Julia Gillard and Cathy Freeman, for example — are exceptional. However, they’ve succeeded by playing in the sandbox in a way that’s in accordance with how society thinks women should achieve things. They played by the rules, they worked within the system, and they won.

That’s amazing, but I also wanted to talk about some more women who refused to play within the system and who weren’t seen as winners or ‘good girls’ by society. We have no problem celebrating the male figures who were like that, but I also wanted to give them some girls!

HAPPY: It doesn’t get any more badass than the Aboriginal bushranger, Mary Ann Bugg. Her story tells us a lot about the cognitive dissonance of reporting on women in the colonial period. Even in the face of all the evidence, she was still regarded as merely an assistant to Captain Thunderbolt who was just a blundering mess…

ELIZA: I’m glad I got that point across (laughs).

HAPPY: (Laughs) But even more disturbing, is the fact that people still visit his grave, and hold him up as the true hero. Are we still guilty of erasing women from history?

ELIZA: I don’t think anyone wakes up in the morning and says, “I can’t wait to erase a woman from history,” but it happens with tiny little things that we do every single day. We’ve given Ned Kelly 11 feature films and TV series — but it’s not about taking away from the boys, no matter how blundering or incompetent I think they are. It’s about sharing and adding a bit more diversity to the spectrum.

I like to think that books like Sheilas are a monument to these women and space for everyone to learn, just like we have so many monuments to men. We need that space to learn about these kinds of women because a lot of the readers — and me — weren’t even given a chance to hear these stories.

HAPPY: At least having access to the stories is the next step in getting a fuller picture of history…

ELIZA: I say in the book a couple of times that “it’s okay if you didn’t know about this woman. You’re not ignorant. Don’t worry about it. This is the fun part of learning.”

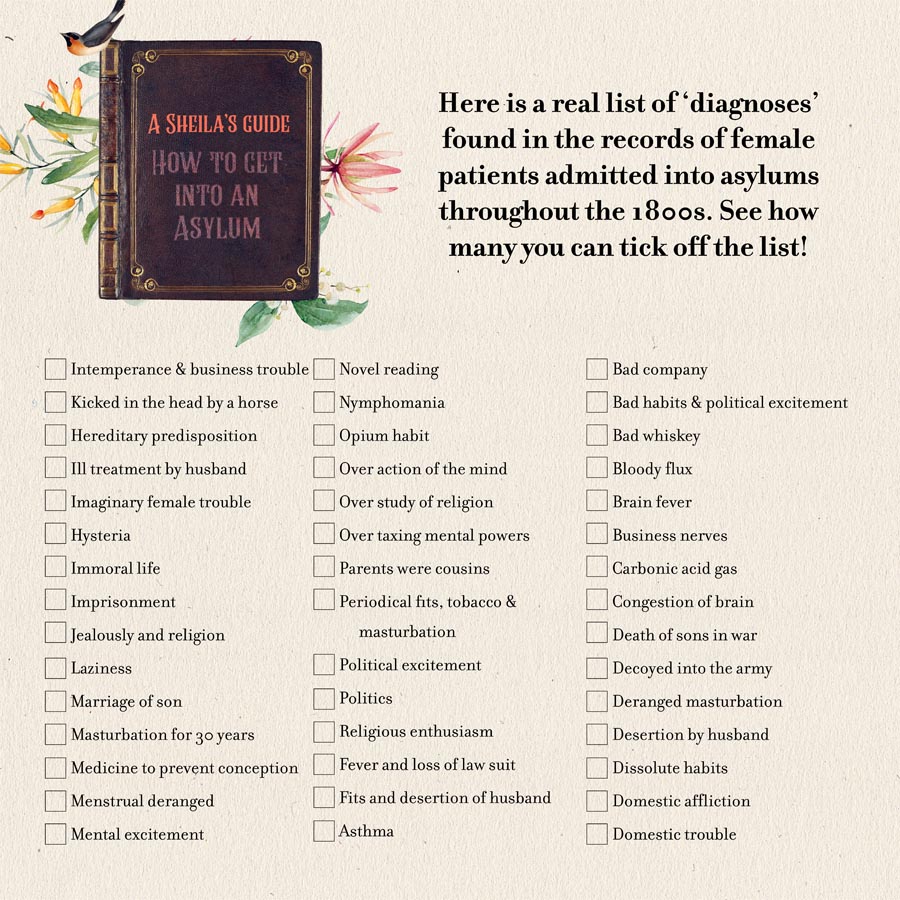

HAPPY: You list literally dozens of ways that women could get locked up in asylums in Australia in the 1800s, ranging from ‘laziness’ to ‘novel reading’ to being ‘bad company’. Women were walking a behavioural tightrope, weren’t they?

ELIZA: The ways that a woman could get locked up in a mental asylum are equally hilarious and so scary. You laugh at first and then you think: “Wait, I think I’ve done all those things today.” It gives me the shivers to think that if I had a fight with my boyfriend, that could lead to him locking me up. Not that he would, but he would have the freedom to do that.

That tightrope of behaviour that women have to walk is still here. Sometimes you have to wait 200 years and look back and see how ridiculous it was. But hopefully by showing that we can look at what we’re dealing with today. Think about Grace Tame. She’s expected to walk that tightrope and still, by some societal standards, she fails in everything she does.

I’m so thankful that a journalist who I talked about in the book, Catherine Hay Thompson, dedicated her life to this cause. Would you ever lock yourself in a mental institution for a story? I wouldn’t. She did it without even giving herself the credit.

HAPPY: Fanny Durack and Mina Wylie were pioneers of Australian swimming and first-rate sheilas, but their path was blocked temporarily by another woman, Rose Scott. What was the deal there?

ELIZA: This is what I love about Shielas. It’s not cut and dry. It’s not goodies and baddies. These are all women who are trying to work things out in a way they feel they can. Rose Scott made life extremely difficult for Australia’s first ever female Olympians, Fanny Durack and Mina Wylie. But she was also a Sheila in her own right by blocking these girls from going to the Olympics. She thought it was the right thing to do for women’s suffrage.

Do you remember that meme that Anne Hathaway posted? In a World of Kardashians, be a Helena Bonham Carter. It was kind of the same thing: you don’t want to be a girl who’s sex-positive and shows off her body. You want to be a clever girl. You want to be an unusual girl. She was unsuccessful in the end: Fanny and Mina went to the Olympics. But Rose is fine now. She’s got, like, a million things named after her.

HAPPY: You have a chapter on the incredible Rosaleen Norton and through her story, you touch on the notion of morality and how it relates to women who aren’t afraid to pursue their passions. Can you unpack that a bit?

ELIZA: Ah yes, I thought I was super-smart when I wrote that too.

HAPPY: (Laughs).

ELIZA: She was the first artist in Australian history to have her work burned ‘by order of the Queen and Crown’. She was arrested several times for ‘immoral practice’. It got me interested in thinking about that word. The insight I gained from researching her story was that morality needs context to be defined. You can’t decide what tastes yum or yuck without having a plate of food. In the same way, we can’t decide if a woman is moral or immoral unless we compare them to a man.

A woman could be thrown into the asylum, or have their work destroyed, but really, it’s just a man’s opinion of a woman. There’s no set standard for what is moral. There’s no set standard woman. My hope is that when a young person is being told that they’re naughty and what they are doing is bad, I want them to be able to stand back and realise that it’s just opinion and separate from fact.

HAPPY: And on that, did writing this book leave you cynical, or more hopeful?

ELIZA: Oh, so hopeful! It made me feel slack-jawed in awe and so inspired. It really pulled back the curtain on the patriarchy and revealed to me how malleable it all really is, in terms of both progression and regression for women. It was only in the ’80s that you needed to get your husband’s signature to buy a house, a passport, or a credit card. It’s great to know that we can make progress, but it does take a lot of tenacity and bravery and those big actionable moments to really shift the needle in history.

HAPPY: And finally: Did you actually try any of those colonial cocktails? They seem strong. And what’s with the eggs and toast?

ELIZA: My sister Hannah and I actually tried making them. She couldn’t actually drive home. I was like, “dude, you’re not actually drinking them, right,” and she’s like, “of course I am.” They were the temperature of blood and it was actually disgusting. But you know what? Colonial Australia also sucked. After a long day of murdering on the Frontier Wars, you have to put an egg in your wine. Eugh!

Sheilas: Badass Women of Australian History is out now via Pan Macmillan.