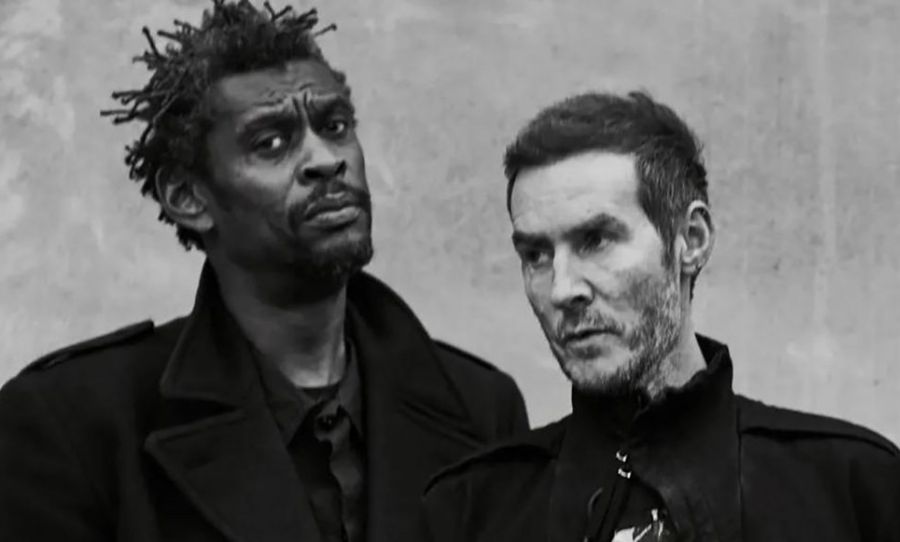

Few artists are able to become so synonymous with a distinctive musical genre as Portishead. Many years before the emergence of Third and alongside fellow Bristol residents Massive Attack, the trio of Adrian Utley, Geoff Barrow and Beth Gibbons catapulted the then infant genre of trip-hop into the mainstream with their critically acclaimed 1994 debut Dummy and their 1997 self titled LP.

Where do you go after defining an entire genre of music? You go on a decade long hiatus and return with a new collection of songs that defy any and all previous expectations.

After becoming the de facto torchbearers for the trip-hop genre, Portishead emerged from the shadows with a dramatically different sound. Here’s what went into the creation of their aptly titled, Third.

Stuck in a Creative Rut

Following years of extensive touring around the world for their first two albums, the members of Portishead, particularly the band’s chief producer Geoff Barrow, burned out. Barrow was worried that the band would become stagnant, and in 1998, he began a three year hiatus from writing and recording music and moved to Australia.

In a 2008 interview with Drowned In Sound, Barrow elaborated on why he needed to take a break from music altogether in the late 90s, stating “I couldn’t find anything I liked musically in anybody, in anything.”

Soon after forming his own label, Invada Records, Barrow was joined by fellow bandmember Adrian Utley as the two slowly began to compose music again. While they were able to lay down the basic foundations for Magic Doors in 2003, a track that would appear five years later on Third, the two were cursed with writer’s block – writing, rewriting, over analysing and scrutinising every note and every tone they produced.

It wasn’t until Barrow and Utley co-produced 2005’s The Invisible Invasion by Coral that things started to get back on track. During the recording sessions, the two became enamoured with Coral’s quick and streamlined writing process, with Barrow claiming (in the same Drowned in Sound interview) “Here’s me and Ade, these older dudes, too scared to even play a note because we we’re scared we’d hate it, and there’s them, just being able to write a soundtrack in an afternoon.”

Feeling reinvigorated and with a fresh new perspective on the creative process, the duo to jumped back into the studio to commence work on a new Portishead album.

Switching Things Up

The band slowly worked on new material across 2005 to 2006, with much on the album being written and completed in the tail end of 2007. Self-produced and recorded in Beth Gibbons’ home studio, Bristol’s State Of Art Studios (of which Barrow is a co-owner) and Utley’s own townhouse set-up, the band used an iZ Radar hard disc recorder, as well as Logic and ProTools to capture and share their ideas for Third.

For their new LP, Portishead knew that relying on their tried and true trip-hop sound would be taking the easy way out. The last thing they wanted to do was to merely satisfy the long standing expectations for a third album based around the milky Fender Rhodes chords, up front bass, vintage jazz soundbites and rhythmic vinyl scratches that the group had become synonymous with.

Taking their inspiration from wide ranging genres – from krautrock and electronica to the dramatic scores of John Carpenter – the band found that one way to shake things up was deviating away from the formulaic verse-chorus approach to songwriting and structuring.

Many of the songs, such as The Rip and Small, feature a slow building and progressive rock style arrangement similar to classic Pink Floyd, while other tracks such as the album’s opener Silence, end on an abrupt note without any closure or musical resolution.

Portishead not only decided to shift their musical style, but the three members experimented with switching instrumental roles as a way of breathing new creative life into the band. Barrow’s bass guitar can be heard on a number of tracks on Third and is situated much lower in the final mix than Utley’s bass playing on their first two LPs, while Gibbons composed many of the album’s keyboard based chord sequences, and even plays guitar on the album’s closing track Threads.

As Utley explained in a 2008 Sound on Sound interview, the band at the time were “looking for limited frequency in instruments… Limited playing, too”, and that their new songs would be better served with a more minimalist and restrictive approach, rather than the more virtuosic route that Utley had long strived for.

Exploring New Soundscapes

Another way that Portishead managed to make Third deviate from their previous efforts was through their choice of instrumentation, throwing away the Fender Rhodes and the turntable scratches that came to become the band’s staple sound.

The band used a ukulele for the first time on the small 90 second interlude Deep Water to suit the track’s doo-wop theme, while the dramatic art-rock track Magic Doors incorporates a saxophone (played by Will Gregory of Goldfrapp) and even features a hurdy-gurdy for a deep, rumbling drone.

Portishead even experimented with how they treated certain instruments they have used in the past. For example, the album opener Silence begins with a heavily delayed guitar line. Yet rather than synchronizing the echoes on the beat, the band deliberately left the guitar echoes out of time with the song’s pulse to create a harsh and tense atmosphere – an indicator to the listener from the album’s get-go that this is not the same band fans had come to know and love in the 1990s.

But perhaps the biggest and most obvious change to the band’s sound was their incorporation of analog synthesizers into the band’s repertoire. All throughout the album’s 49-minute duration, the tracks are scattered with various classic old school synths such as the Minimoog, Korg MS-20, EMS VCS 3 and many more that aided the band’s exploration into the realm of electronica.

For quite a lot of the album, the analog synths are used in more of a textural way, used to create the soft swells in Nylon Smile, the oscillating pulsing rhythm of We Carry On, as well as the Apocalypse Now-esque chopper sounds the lurk in and out of Plastic (created through an ARP 2600).

The synths are also used in more melodic instances, best displayed in the tail end of Machine Gun. Sampling a drum beat from a beaten-up Orla Tiffany 4 Organ, Portishead used a Siel Orchestra to provide a Blade Runner style synth string lead that contrasts perfectly with the track’s abrasive beats.

A Link to the Past

Throughout Third, it appears that the only real remnant to the band’s iconic, mellow trip-hop style is Gibbons’ haunting vocal deliveries. While the band primarily used an AKG C414 to capture Gibbons’ vocal performances for their first two albums, they opted for Rode NTK Valve Condenser Microphone that provides her vocal performances on Third with a crisp and warm quality.

As for effects, many of the vocals across the album are gently affected with modern reverb plug-ins from Altiverb and stock ProTools varieties, but the band also makes extensive use of Adrian Utley’s vast collection of vintage gear.

With rare Neumann and Calrec EQs and a slew of retro limiters and compressors on hand, the most used piece of gear on Gibbons’ vocals for Third is a Great British Spring – a late 1970s spring reverb housed within a long piece of plastic drainpipe – and provides many of her vocal performances with an eerie quality.

Yet the new, dramatic and highly abrasive tone Portishead unleashed on Third provides the perfect contrast to Gibbons’ soothing delivery. Juxtaposing with the gradual slow build on Silence, the brutal beats of Machine Gun and the climactic conclusion of Threads, Gibbons’ lyrics on love, intimacy and hopelessness create a powerful sense of unease that doesn’t let up until the album’s conclusion.

After releasing two critically lauded albums that thrusted the trip-hop genre into the ears and consciousness of millions of listeners, Portishead found themselves pinned against a musical wall, destined to create and recreate the jazz tinged dinner party music for their hungry fans.

Third isn’t just change for the sake of change – it’s a musical testament to how time can dramatically change who we are. Progressive, primitive and downright unsettling at times, Third may have proved to be a shock to many upon its initial release, but it captured the dramatic essence of what made the band so great to begin with – albeit with distinctly different instrumentation.

If fans have to endure another 11 years of silence from Portishead, it’ll be well worth it.