Born from a radical zeal for innovation and the pursuit of commercial success, Fender offsets cast an imposing and asymmetrical shadow over the history of rock ‘n’ roll.

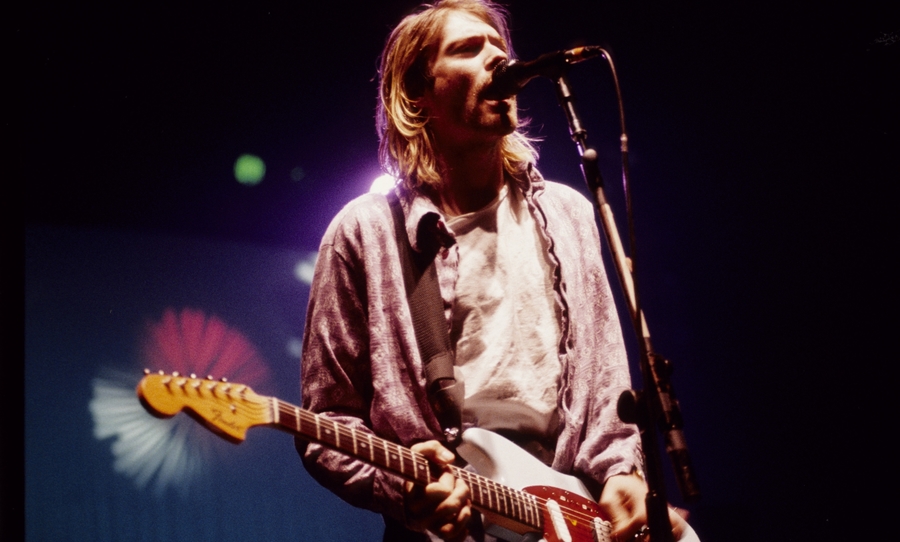

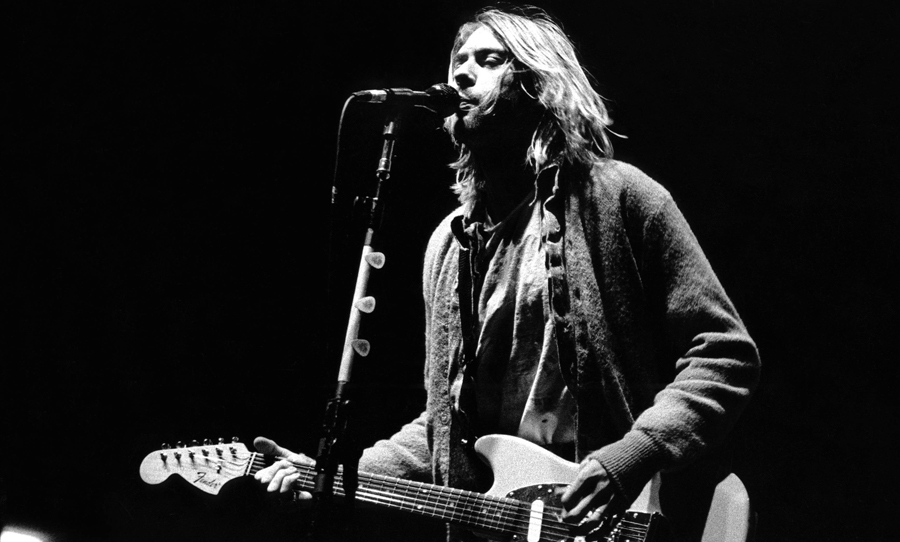

It’s a series of guitars that’s shaped rock ‘n’ roll – from ‘60s surf rock to ‘70s punk to ‘90s grunge – not merely musically, but also in aesthetic. The Fender offsets, so called for their asymmetrical offset bodies, have been a boon to new learners and the more petite among us, alongside the likes of Kurt Cobain, Liz Phair, Sonic Youth, and My Bloody Valentine.

Although they were discontinued in the ‘70s, the wave of alternative and grunge in the ‘90s essentially brought them back. Since then, the offsets have remained a staple in Fender’s catalogue.

The first offset to come into this world was the Jazzmaster in 1958. As suggested by its name, this entity was designed specifically to be played by jazz guitarists while seated. However, thanks to its unique tremolo bridge, it also caught the attention of the ‘60s surf rocker scene.

The Jazz Bass followed a similar trajectory. Produced originally in 1960 for upright jazz bassists, the product became a hit with rockers (as well as jazzers) and by the next year, Fender had put out the VI 6-string offset bass.

On a roll, Fender’s next offset was the Jaguar, released 1962. With chrome details and an extra fret – 22 instead of the typical 21 – the Jaguar practically became the spokesmodel for the business.

Next came the Duo-Sonic, Musicmaster, and the iconic Mustang, all in 1964. Deriving from a “student” series that began in 1956, this lot were remodelled for the offset trend to become even smaller, lighter, and more playable than they already were.

The Jazzmaster – Master of Everything Except Jazz

As the first of its kind, the Jazzmaster offset was advertised by Fender as having “a novel combination of recesses and bevelled portions, thereby promoting ease and facility of playing with minimum discomfort to the guitarist.” Geared towards the more well-heeled jazz musician, the Jazzmaster was retailed at $325.50.

Yet, it never really took off with its intended demographic; instead, it was co-opted by the surf rock scene, chief among them The Beach Boys themselves. As surf rock went out towards the end of the ‘60s, the instrument then became the darling of ‘70s punks.

The Jazzmaster boasted an innovative dual-circuit, the idea for which originated from Fender factory boss Forrest White back in the 1940s – though at first, Leo Fender himself wasn’t convinced:

“I said to Leo, what you need is a guitar where you can preset the rhythm and lead. Leo didn’t play guitar—he couldn’t even tune a guitar—so he didn’t think this was important.”

It wasn’t until after jazz guitarist Alvino Rey came to the factory and requested such a guitar, that Fender changed his tune, bringing out the dual-circuit Jazzmaster and Jaguar soon after.

Said dual-circuit worked on the Jazzmaster via an up-down switch, the latter for the lead circuit, with a three-way switch for the pickups (similar to the Telecaster); meanwhile, the “up” position accessed the rhythm circuit, which used only the neck pickup – but with a different sound quality than the lead circuit’s use of the same pickup.

The Jaguar – Ahead of the Pack

Due to the Jazzmaster’s popularity among surf rockers, early ad campaigns for the Jaguar boasted a shameless “beach” theme (“for surfing sounds nothing beats the Jaguar,” claimed one old Fender poster). Fender was on the lookout for more profit, pricing the Jaguar at $379.50 – or $398.49 with a custom colour finish!

Indeed, the Jaguar marked Fender going bigger and better with its offsets – or rather, smaller and better. Its 24-inch scale was unprecedented and tapped to appeal to the smaller-handed guitarist, among them employees of Fender itself (Forrest White was one such advocate).

Offsets were also offered were four different neck widths – a normal, a narrower than normal, and two wider than normal (a range with which Fender updated the Jazzmaster too from 1962).

Another shiny feature of note was the metal cradle design of the Jaguar’s pickups. This, in Fender’s own words, was to make them “relatively insensitive to extraneous electro-magnetic fields so that the amount of noise generated in the pickup and associated circuitry is minimized.”

Carrying on the Jazzmaster’s innovation, the Jaguar was also dual-circuit, but in a slightly modified fashion. It came with three switches on the lower body to control the neck pickup, bridge pickup, and bass cut; additionally, there were two master volume and tone knobs for the lead circuit only.

The Mustang – Apple of the Alt-Rock Eye

As the first of the “student series” offsets, the Mustang was modelled after the Jazzmaster, with the same style of offset body and tremolo bridge. Naturally, with its nonchalantly irreverent allure, it took off with grunge and alternative rockers.

Following in the Jazzmaster’s footsteps, the Mustang offset also got its own bass version! The Mustang Bass was, in fact, the last original bass designed by Leo Fender himself, with a 30-inch scale and single split pickup (similar to the Precision).

In 2013, the bass was relaunched, with the same scale but with an added Jazz-style bridge pickup. This “PJ” pickup configuration, in confluence with a three-way pickup switch, allows an even bigger and more versatile sound.

Although the original Mustang line was discontinued by 1982, a re-emergence came about in the late ‘90s with the Squier series, which included Courtney Love’s Squier Venus a.k.a. the Vista Venus (the second female signature Fender, after Bonnie Raitt).

After that followed some tentative new Mustang releases (including the Kurt Cobain signature), then in 2016 Fender went all out, with reissues of the Mustang, the Mustang 90, and the aforementioned PJ basses. Like the ‘60s originals, the new Mustang guitars boast a 24-inch scale, but also come with some changes – namely, a hardtail Stratocaster-style bridge instead of tremolo.

Undoubtedly one of the most influential proponents of offset guitars was Kurt Cobain. How better to end our journey than with a “glowing” recommendation of his Mustang in a ’92 Guitar World interview. It reminds us that influence need not equate to perfection:

“They’re cheap and totally inefficient, and they sound like crap and are very small. They also don’t stay in tune, and when you want to raise the string action on the fretboard, you have to loosen all the strings and completely remove the bridge. You have to turn these little screws with your fingers and hope that you’ve estimated it right. If you screw up, you have to repeat the process over and over until you get it right. Whoever invented that guitar was a dork.”