Demos are a curious thing. They are a song in its before-life (if afterlife is after death, then before-life is the opposite). Yet, inevitably, they are doomed to exist in the shadow of their more polished twin. But for anyone who’s ever written music, you know that sometimes you can develop a strange connection to those early versions.

Sometimes you even like it more than the final product. It’s a phenomenon called ‘demoitis’ or ‘chasing the demo.’

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 14. Grab your copy here.

Everyone knows there’s magic in a first take. But has the increased ease of recording a demo made them any less worthy of worship?

The influence that the process of demoing has on the final song is undeniable, and the way that a demo is recorded can affect the final outcome. But the art of demoing is something that has morphed over time, subject to the ever-changing technological world upon which it’s dependent.

Once upon a time, demos were created on cassette tapes or reel-to-reel. They were raw, unaltered versions of the song, perhaps the song in its purest form. They sat distinct from their final, fully mastered alter-egos. Nowadays, the boundary between demo and final form can easily dissolve. Demos are readily fleshed out in DAWs like Pro Tools, Ableton, or Logic. A file that starts out as a demo can be refined until that same file is the finished product. But through this process of refinement, is there something we have lost?

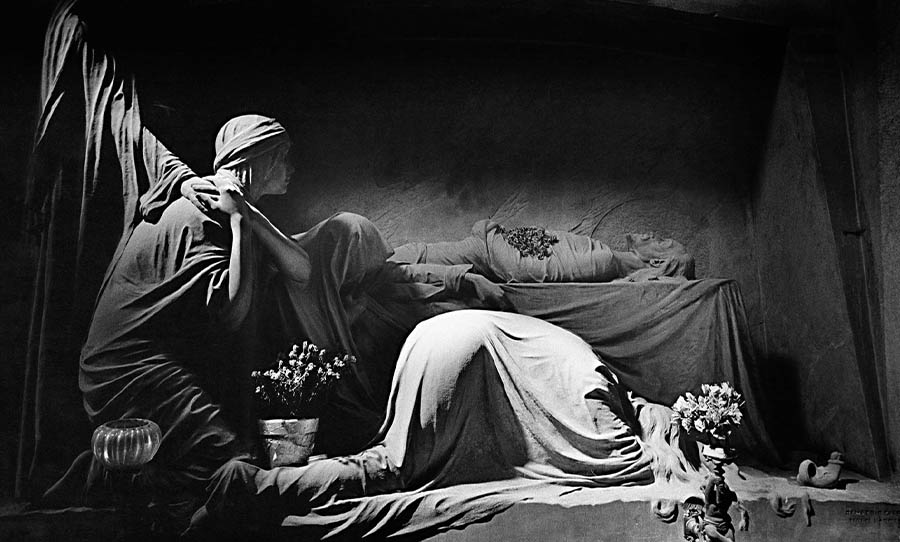

Many of the greatest songs have lesser known demo forms. Shadow selves, you might call them. A fraction of these can be found online, posted by the band themselves or producers who recorded them. They represent the song in a different form, an alternative reality. They are fascinating to discover.

One such example is Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Many wouldn’t know that the track was originally named Starlight, the chorus lyrics declaring: “We need some starlight, starlight sun / There ain’t no second chance, we got to make it while we can.” Starlight was written by English producer Rod Temperton yet after spending a night brainstorming album titles, Temperton awoke the following morning with the word Thriller in his mind.

“You could visualise it on the top of the Billboard charts,” Temperton described in a 2007 interview. “You could see the merchandising for this one word, how it jumped off the page as ‘Thriller.’” Deciding that Thriller had more commercial appeal, he changed the title of the track and the lyrics along with it.

There are plenty of other stories like this. Rather than the now familiar “With the lights out, it’s less dangerous,” the original chorus lyrics to Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit were “I’m a liar and I’m famous.” Before Blondie’s Heart Of Glass became the hit it’s remembered as today, the song was originally titled Once I Had Love (the band themselves referred to it as The Disco Song). Significantly slower than the final cut, the early demo seemed better suited to soundtrack a trip to a tropical island than a night on the dance floor.

In those days, new bands would often send their demos to record labels through the mail. These rough and ready recordings would represent an idea of what the final song could be, and if the label accepted, a record deal would see the songs reborn through fresh production. One such example was Joy Division.

After signing a deal with Tony Wilson of the now-famed Mancunian record label, Factory Records, Joy Division went to record their debut album in 1979. Taking their demos to producer Martin Hannett at Strawberry Studios, they started work on Unknown Pleasures. Yet Hannett’s vision for the album was different to what the band had in mind. Rather than the rocky, aggressive record they had envisioned, Hannett’s final version of Unknown Pleasures turned out subtle, dark, and cavernous.

“We played the album live and heavy,” Joy Division guitarist Bernard Sumner once described. “We felt that Martin toned it down, especially the guitars. The production inflicted his dark, doomy mood over the album; we’d drawn this picture in black and white and Martin coloured it in for us. We resented it but…Tony [Wilson] loved it, the press loved it, and the public loved it. We were just the poor stupid musicians who wrote it.”

Ironically, bassist Peter Hook later described that what he initially hated about the album – Hannett’s spacey, echoey sound – was what he eventually came to love about it. Whilst the final Unknown Pleasures went on to become a landmark post-punk album, the world will never know the Unknown Pleasures originally imagined by the band themselves – for better or for worse.

These days, demoing has become a lost art. But despite the slickness of modern technology, sometimes demos can still emerge in unexpected places. It’s not uncommon for people to use elements from a demo in a final mastered version. Some modern albums include recordings made on iPhones, and others have even used demo vocals recorded on laptop speakers in the final version.

Perhaps ‘chasing the demo’ syndrome simply comes down to a psychological bias, a preference we have for an older, more familiar version of our song. But then again, perhaps sometimes there is something special – a magic and warmth – captured in a first performance that we discover is gone upon recreation.

In the end, whether or not demos contain something special, most often they are abandoned. They are renounced as relics, ghosts which linger only in digital memory, rarely serving any purpose. But isn’t that the beautiful thing about the early days of technology, those little oddities? The further we move away from that time, the more it feels like there is some quirk, something strangely human, that we have lost.

This article appears in print in Happy Mag Issue 14. Grab your copy here.