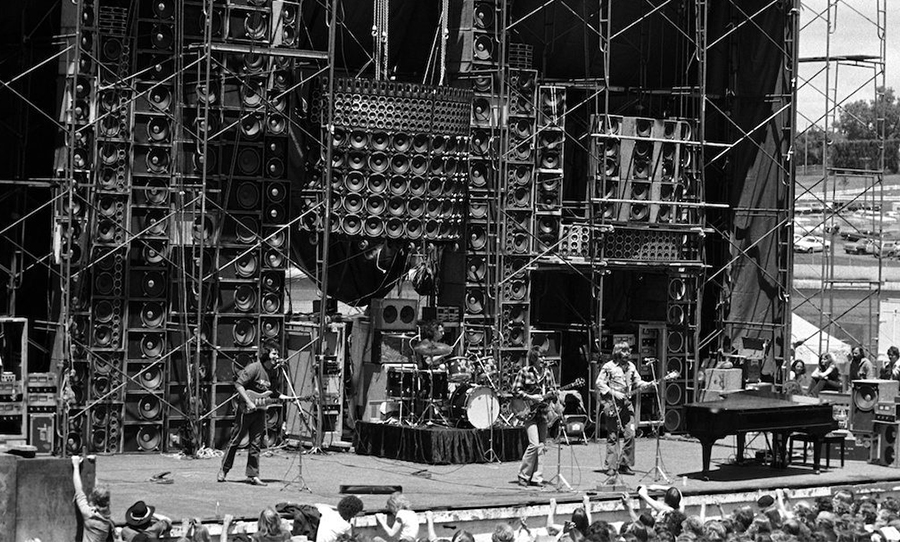

It looks excessive, but there was a method in Owsley’s madness when he designed the Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound. Those who heard it say it was the best live sound ever.

On a night in 1974, sound engineer Stan ‘Bear’ Owsley stood alone in an empty theatre – the former Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. Rumoured to have especially sweet sonic qualities, the venue was a converted ice rink and by this point was showing wear from decades past. Despite this, some of the biggest names of the 70s had graced its stage: Pink Floyd, Queen, The Stones – you name it. This night, however, was the Grateful Dead’s turn, and they had brought some heavy artillery with them – the Wall of Sound.

Owsley stood before a three-story behemoth. A solid wall of over 600 speakers. A feat of engineering only he could dream of, let alone accomplish. He was perched on the stage, mixing and testing the sound; a gentleman on the shorter side, he was especially dwarfed by his brainchild. Tears streamed down his face and he whispered to the mass of wood, metal, and wiring, with the tenderness of any parent witnessing their child’s first recital.

“I love you and you love me—how could you fail me?.”

The Dead’s intermittent drummer Mickey Hart told Rolling Stone about walking in at this very moment.

“We heard somebody sobbing and we went over to the side of the stage and Bear was talking to the amplifiers. He was addressing these electronics as if they were a person. At first, Bill and I were laughing, but then we said, ‘Wow, he’s really serious.”

And serious Owsley was. The mad-genius knew that sometimes you have to push the envelope and sometimes you just do it because you can. Was his ludicrous wall built just for the sake of it then? Definitely not, the Wall of Sound was state of the art and changed the way technicians thought about live engineering. It was free of all distortion and served as its own monitoring system and solved many, if not all of the technical problems that sound engineers faced at that time.

Did it need to be quite that big?… Probably not, but it did look damn impressive.

A Need for Noise

People have a romanticised view of live concerts in the 1960s and 1970s, and for good reason. Rock and roll was in its adolescence, constantly growing and evolving. Legendary shows were held featuring artists who defined generations. Live sound, however, had not kept up with the growth spurt and, simply put, the primitive public address systems of the time were just not as good as the music.

These days, it’s common to hear younger audiophiles and keen fans complaining about the sound after a gig. Probably just as well they weren’t around to hear the primitive live setups of rock concerts back in the day. In the ’60s it wasn’t uncommon for bands to solely use the power of their amplifiers to project to the crowd. Early P.A systems were usually reserved for the vocalist alone. ‘Mic’ing up’ amps, then, was a new idea.

Even if a band had the luxury of amp mics, monitors were unheard of. The band would only hear themselves after the sound had bounced around the walls of the given room and the bodies of the audience. They would often hear a version of the sound that was delayed, and with reverberations produced by the club, hall or stadium. There was a reason why The Beatles stopped touring in 1966. Their VOX amps and diminutive P.As (which were basically cinema speakers) couldn’t fill a stadium, let alone compete with thousands of screaming fans. The four found their sound was less fabulous than they were, and they simply couldn’t hear themselves play.

As the ’60s rolled on, sound engineers began to experiment with different P.A. systems for broadcasting sound to larger audiences. Early setups saw P.As positioned level or slightly in front of the performers. Amplifiers would battle with the P.As, competing for volume and sound space. The result, more often, was ugly: colliding frequencies, distortion and feedback issues were the norm.

Bill Hanley made a leap forward while working with Neil Young, during his time with Buffalo Springfield. He was the first to angle a speaker towards the player, using directional microphones to cancel out feedback. Hanley was so well regarded that he went on to design the sound for Woodstock and is often regarded as the “father of festival sound”.

Monitor technology gradually improved as the decade rolled on, making it easier for performers to hear themselves and the rest of their band clearly, resulting in better tuning, timing and a tighter performance altogether. It goes without saying, singers who could hear themselves didn’t have to strain their voice just to hear themselves, drummers didn’t have to beat their skins off, bassists could minimize their mud and lead guitarists, well they stayed about the same.

In those early days of rock, however, such technologies were still in their infancy and there was a great need for innovation in live sound design. The Grateful Dead and their ragtag group of roadies and Deadheads were known for a DIY, self-sufficient attitude, and began to take matters into their own hands.

The Dead and Their Devious Designer

The Grateful Dead were hippie royalty. A band formed in the San Fransico bay area during the heady days of the mid-1960s, they quickly developed a huge cult following. Stan Owsley was a good friend of theirs – a sound guy, acid chemist, and ex-professional ballet dancer. So a triple threat you might call him.

Owsley had studied engineering at the University of Virginia, before dropping out for a stint in the air force. He moved onto some serious ballet training, and after he felt that part of his life was over he enrolled at the University of California. It was here that he became involved in the blossoming psychedelic scene. Owsley was the first private entity to manufacture commercial quantities of LSD, at a time when it was all still legal. He even supplied LSD to the Beatles during the filming of Magical Mystery Tour. Talk about living multiple lives.

He met the Grateful Dead through Ken Kesey, during one of his infamous ‘acid test’ parties in 1965. Owsley, or ‘Bear’, as he became known, began to work with the band as their sound man and financed them with his earnings cooking acid. Along with his good friend Bob Thomas, he helped design the iconic lightning bolt logo, which would go on to assist in the sale of countless t-shirts from hairy, caravan driving, carpark merchants.

After a hallucinatory incident, where Owsley ‘saw’ the Grateful Dead’s sound, he became obsessed with aural perfection and started on an endless path, working with the band, to achieve it. Bassist Phill Lesh recalled the beginning of this journey to Rolling Stone.

“I started talking to Bear about our sound problems. There was no technology for electric instruments. We started talking about how to get around distortion and get a pure musical tone. He did some research and said, ‘Let’s use Altec speakers and hi-fi amps and four-tube amps, one for each instrument, and put them on a piece of wood.’ Three months later we were playing through Bear’s sound system.”

Owsley continued to develop his craft and work on live sound for the band, amongst other groups in San Fransico. Always striving to improve, Owsley kept a ‘sonic journal’ of each performance, so he could improve on his setup and mix for each concert and highlight issues to the band.

“The one thing I insisted on that they did listen to me about was, I insisted on sound checks, and I encouraged them to listen to tapes of their performances,” Owsley stated in some biographical notes, “not just so they could hear how they sounded, but also to correct me on what I was doing, because I tried to make the tapes as much like the way it sounded in the hall as possible. This way I learned to mix sound.”

It is rumoured that Owsley took inspiration from Buffalo Springfield’s monitoring setup, during a concert where they shared the bill with the Dead. Monitoring allowed the band to hear themselves fairly well, but Owsley was not satisfied with the standard speakers and amplifiers that were available to him, so he and his apprentice clandestine-chemist Tim Scully began modifying and manufacturing their own audio gear. He went on to create a workshop in the Grateful Dead’s rehearsal space in Novato, near San Fransisco, which eventuated in the founding of the company Alembic.

Alembic became highly prolific in sound recording, modifying and repairing guitars, basses, and P.A. systems. Before long they were creating their own products, and in a few short years, Alembic incorporated three shareholders: Ron Wickersham, the electronics expert, Rick Turner, a luthier, and Bob Matthews, a recording engineer, all who would later help out on the Wall of Sound.

In 1969, a meeting took place between Bob Weir, Phil Lesh and Jerry Garcia and a small group of their close collaborators. The group brainstormed ideas for musical exploration and solutions for their technical problems, over a few spicy cigarettes. It was here that Owsley proposed putting the P.A behind the band. A casual, stoned suggestion that would change the way audio engineers thought about concert sound.

His reasoning was that the audience and band would hear the same thing: no delays, no chaotic reverb, no colliding frequencies and minimal-to-no feedback: the same mix broadcasted from a unified backline. At the time it seemed like a crazy idea, and most of the group assumed a single vocalist’s mic could drown the whole mix in feedback if pointed at the mass of speakers. But Bear Owsley disagreed.

The idea didn’t bloom straight away, but the seeds were planted, and as the Dead’s audience and crew kept growing, experimenting with some out-there ideas didn’t seem so crazy.

The Wall

It turned out that cooking acid became illegal, but that didn’t stop Bear Owsley. The police did. In 1967 he was caught with 350,000 doses of LSD and 1,500 doses of STP and spent three years in the grey-bar hotel. Upon release, Owsley resumed work for the Dead, but only for a few short months, before he was institutionalised again for possession. This particular event was immortalised in one of the bands greatest hits, the 1970 song Truckin’:“Busted, down on Bourbon Street / Set up, like a bowling pin, Knocked down, it gets to wearing thin / They just won’t let you be.”

Owsley was released in 1972 and resumed his role again as the band’s sound engineer. Crowds were getting larger, and much of Owsley’s former job had been delegated to roadies who were more than happy to keep the setup easy so they could join the party. His frustrations can be heard in an interview with Grateful Dead biographer Dennis McNally:

“I found on my release from jail that the crew, most of whom had been hired in my absence, did not want anything changed. No improvements for the sound, no new gear, nothing different on stage. They wanted to maintain the same old same old which under their limited abilities, they had memorized to the point where they could sleepwalk through shows.”

Bear, however, was never one for complacency, and upon his return, endeavoured in his most ambitious design to date. He, Dan Healy and Mark Raizene of the Grateful Dead’s sound team collaborated with Ron Wickersham, Rick Turner and John Curl of Alembic. Together they created the legendary Wall of sound. What was it exactly? Well in Owsley’s own words:

“The Wall of Sound is the name some people gave to a super powerful, extremely accurate P.A system that I designed and supervised the building of in 1973 for the Grateful Dead. It was a massive wall of speaker arrays set behind the musicians, which they themselves controlled without a front of house mixer. It did not need any delay towers to reach a distance of half a mile from the stage without degradation.”

The behemoth used six separate sound systems which were able to isolate eleven separate channels. Vocals, rhythm guitar, piano each had their own. Another channel each for the bass drum, snare, tom-toms, and cymbals. The bass was transmitted through a quadraphonic encoder, which took a signal from each string and projected it through its own set of speakers.

The result of each speaker carrying only one instrument or voice at a time, was crystal clear audio, free of intermodulation distortion. Up until this point, it was common to have a lead guitar pulling the speaker cone one way, and the bass stretching it another. With these primitive P.A designs, a mix could end up sounding pretty chaotic and even sap the magic out of a solo. For a taste of what it was like to be in front of the Wall, have a listen to these archival recordings of a 1974 Roosavelt Stadium Show.

Owsley’s grand design was also the first of its kind to eliminate the need for a sound guy, at least at the front of house. In addition to monitor controls, each of the microphones had volume dials. The idea was that each band member could adjust the sound in real time. The situation of the monitors gave the band the power to control their own sound. As Owsley so eloquently put it in some biographical notes:

“As far as I’m concerned, the sound man should be as superfluous as tits of a boar hog… All he should do is make sure things run and don’t break down; plug the wires in and unplug them. All the control of what’s going to the audience should be fully in the hands of the performing artists themselves. That’s the only way you’ll ever get close to true art.”

Another benefit of this system was that audience members heard the instruments, and voices, where they saw it, through the same channels as the band members. Each channel of speakers was representative of the space of the performer, the stereo image resulting in an acoustic-like realism.

There were numerous renditions and developments of the Wall, but the largest version used 586 JBL speakers and 54 Electrovoice tweeters and was powered by 48 McIntosh MC-2300 amplifiers, which resulted in a continuous 28,800 watts. It stood three stories high and about 30 meters wide, the first line array system of this scale ever assembled. High-quality audio could be heard at 200 meters, with decent sound up to another 200 metres, at which point wind started to degrade the audio.

It sounds excessive, and perhaps it was. However, at the time it seemed adequate, seeing as outdoor Grateful Dead concerts were regularly attracting audiences of over 100,000.

The wall was not built overnight. The design and build process took months, with many ‘proto-walls’ being constructed to test the complex system. One example was used in 1973 at a Stanford University concert, where every tweeter in the system blew as the band began their first song. A year later, the bulk of the wall was complete, however, it required continual development throughout the short history of its use. The completed Wall of Sound made its touring debut on March 23, 1974, at the Cow Palace in Daly City, California.

Troubleshooting

The Wall solved a huge number of the bands sound problems, however, understandably, the system created a number of technical issues of its own.

One of the early problems that surfaced was issues with feedback between the speakers and the singers’ rear-facing vocal microphones – something that had been a concern voiced by the band in the initial brainstorming for the Wall. Owsley made quick work of this problem. He and the Alembic team designed a specialist microphone system, placing matched condenser pairs, run out of phase, 60mm apart. Jerry or Bob would sing into the microphone sitting on top, the bottom mic picking up all the other sounds present on the stage. These signals were then blended with a differential summing amplifier, which acted as a noise canceller, eliminating common sounds across the signal, resulting in just the pure vocals being amplified.

Of course, physically mounting the system was an immense task. If anyone had some qualms with the job, it was Richard Pechner, a roadie, carpenter and photographer for the band, who assisted in the mammoth construction job. In an interview with Audio Junkies, he described the task of stacking the centre cluster:

“One of the biggest issues was “stacking” the speaker columns and positioning of the centre cluster. As the speaker columns grew in height, the logistics of hand stacking them became dangerous. Those 15″ bass cabinets of Phil’s were no picnic to move around let alone lift and stack.”

A solution was found by using a mechanical winch to haul the speakers into place. When drummer Bill Kruetzmann saw the massive object sitting above his kit for the first time he refused to play under it, insisting the drum platform be moved forward (fair enough).

Another roadie named Steve Parish reminisced that system took 21 crew members all day to set up: “You had to get up at 6am, it took all day to put it up, but we had it down to a science.”

Half of the day was dedicated to mounting the speakers, before a short lunch break. The rest of the routine was 4 hours dedicated to taming the potential rat-nest of wiring.

The roadies would also go out of their way to set up the next show early, with a couple of sets of staging and scaffolding, essentially leapfrogging from show to show. On top of this, it took four semi-trailers to haul 75-tonnes of amps, speakers, subwoofers and tweeters. It goes without saying, the Wall of Sound was a logistical nightmare.

Pechner remembered that he overheard a tense band meeting, discussing the total cost of designing and testing the system – $275,000, which he thought that was a pretty conservative estimate (this did not consider the regular costs of paying the large crew, as well as transport and maintenance costs). Regardless, it was a monumental amount for 1974, a figure that today would be well into the millions.

It’s no surprise then that the Wall of Sound almost sent the Dead bankrupt, almost as soon as it rose the roof, it was time to pull it back down again

The Legacy of the Wall

Parts of the wall were kept, repurposed and recycled for future touring rigs, however other parts were sold off. Legend has it that friends of the Grateful Dead, Hot Tuna and Jefferson Starship snapped up some of the highly sought-after top-of-the-range gear. Nonetheless, the Wall the way live sound engineers thought about their designs.

Touring companies picked up on what the Grateful Dead were doing, particularly the line array rigs – convenient packaging designs which allowed crews to pack substantial wattage in semi-assembled sections, minimising set up times and overall costs. Unlike the Wall, subsequent live sound designs, have obviously required an engineer to operate the system. They also don’t have dedicated amps and speakers for each instrument – this has been somewhat countered with modern improvements in these technologies.

Today’s amplifiers have the benefit of being a lot more powerful and lightweight than the Wall’s McIntosh Mc-2300s, which individually weighed 58kg. Modern concert amps can be a sixth of this weight, drastically cutting transport and crew costs. Live sound engineers have taken note of Owsley’s experiment, and as technology improved, found ways to offer greater consistency, but perhaps not with the same specific clarity and detail.

Deadheads and engineers who were lucky enough to hear the Wall in all its glory claim that in terms of clarity of sound it still hasn’t been beaten. There have been more powerful speaker systems built sure, but in terms of sheer, unbridled engineering, in a time where there was nothing like it on the planet, it remains unparalleled.

Perhaps bassist Phil Lesh sums it up best: “I thought it was absurd, but it made me giggle… excess for sure, but we were known for that.”