In a world where physical music sales are dwindling, the future and purpose of the hidden track is unclear.

I can think back to a time when my CD collection was my most prized possession, not to mention the most expensively assembled part of my identity. I would save my pocket money and meagre earnings until I had amassed the requisite amount, normally in the region of $30, to make the pilgrimage down to the local music store.

I would roam through the genre-specific aisles examining new releases and my favourite artists’ designated sections, desperately hoping to find something of importance. Something of rarity. Something with meaning.

When I was a teenager, my default position was that music had an inherent meaning. That it was designed to be examined, decoded and understood. I’ve always had a difficult time turning it up and tuning out. Hits and ‘bangers’ have rarely held my attention for long.

By design, hits aim to appeal to their audience immediately; blowing their load and showing their hand simultaneously in the hope that the listener will succumb to their advance and take them home for a steamy, yet superficial affair. Anything requiring deeper analysis within this context is arguably self-defeating.

Hidden tracks, on the other hand, were right up my alley. They suggested something more romantic and multi-faceted; the part of an artist’s persona that they hesitate to share, yet are compelled to all the same. Their obstructed accessibility implied that they were exclusive in some way – that they were included for the hardcore fans, those that understood the best treasure was the most hidden.

However, in recent years we have witnessed a decline in the number of hidden tracks being produced. In a world where physical music sales are dwindling, and the majority of people listen to music in digital formats, the future and purpose of the hidden track is unclear.

Firstly, for a track to be hidden it needs to exist within the context of a whole release, which is no longer a given considering that people today often prefer to experience music through curated playlists and streaming services. Secondly, surprises aren’t really a thing in the digital world. You won’t be surprised that an unlisted song starts because your player will inform you that it’s there.

The relationship between physical music production and hidden tracks, and the context in which it formed, is critical. When music was still predominantly consumed and purchased through physical means, there were unique opportunities in terms of controlling how the listener would experience a release. Of course, this was limited; a listener has always had the power and agency to skip tracks, but through these minor obstacles artists and producers were able to suggest an experience they deemed superior.

Because of the characteristic limitations of vinyl and compact discs, conventions and accepted wisdoms eventually formed. However, these same limitations allowed novel approaches that subverted audience expectations and brought attention to the artistic process itself. Through various techniques, artists could choose to ‘hide’ materials within their releases.

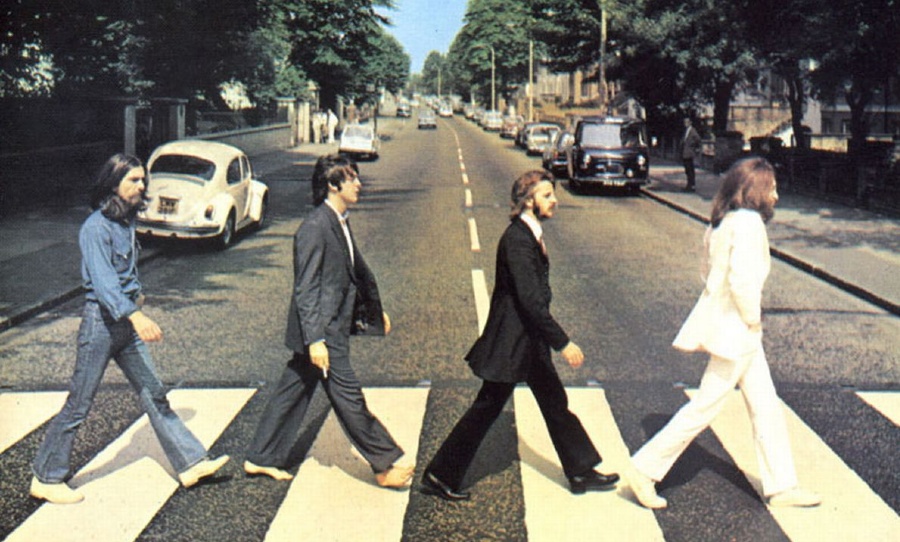

The Beatles included the track Her Majesty on Abbey Road but chose to leave it out off all listings and associated material. The rationale for this has never been confirmed. However, it seems likely that it was either an unintentional oversight or a decision based on the track being considered minor in length and importance to the album.

My Chemical Romance hid Blood a minute and a half after their album The Black Parade appears to finish. The lyrics appear to parody the self-serious culture of emo music at the time, and comment on the genre’s perverse relationship with sorrow. It’s the equivalent of a wink at the end of a performance that encourages the audience to question the nature of what they have just witnessed – soul-baring confession, or entertaining theatre.

Super Furry Animals actually hid a track five minutes before their third album Guerrilla even started, meaning that it could only be accessed by hitting rewind on the CD player. This inaccessibility seems to be a cute response to the rest of the album’s ‘accessible’ pop leanings.

As you can see, the underlying rationales behind each track are divergent. Some are hidden messages, some are postmodern attempts to break the fourth wall. Some are simply dumb jokes. However, the fact that they are hidden amongst the rest of the release gives them a certain mystique. They feel distinct in a way that’s difficult to put one’s finger on; their existence a consequence of personality rather than business or logic.

This isn’t to say that the current music landscape is dull and without character because it lacks hidden tracks. Artists are arguably more inventive in terms of releasing their music and surprising their audience than ever before. Unannounced mixtapes and releases, such as Frank Ocean’s Blonde, create unhinged hype and can send the online world into a manic frenzy that’s reminiscent of the fabled golden eras. It might not be Woodstock but it’s fresh, exciting, and very much of our time.

Despite this, I can’t help but shed a tear for the hidden track and all it symbolised to me as a young person. As the way we consume music changes, certain aspects of what made that experience unique and captivating morph and disappear. To stand on a soapbox and complain would be arrogant and nostalgic in a destructive and negative way. However, I can’t help but wonder what is lost.

Hidden tracks are symbolic of hidden meaning, the underlying belief being that the rest of the music has meaning too. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that in a world where music seems more disposable than ever, the hidden track’s absence is so keenly felt.