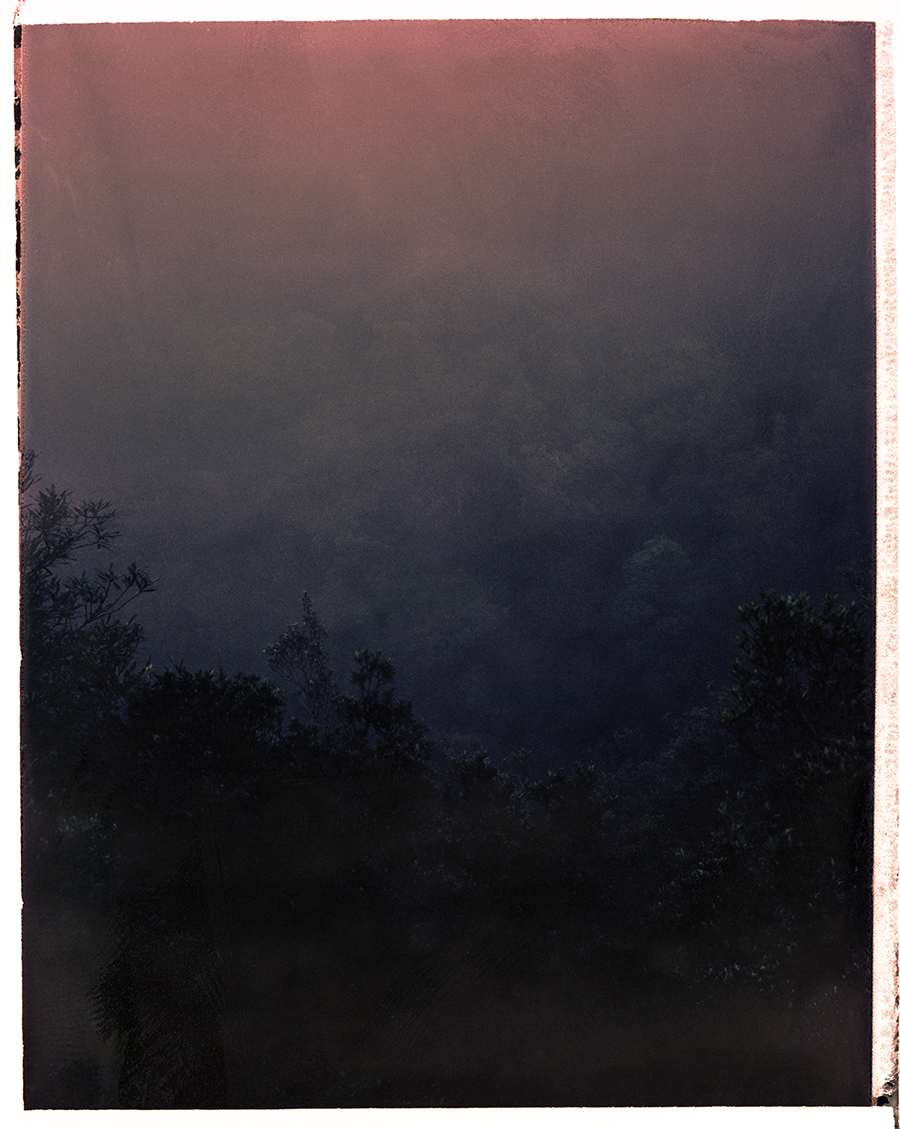

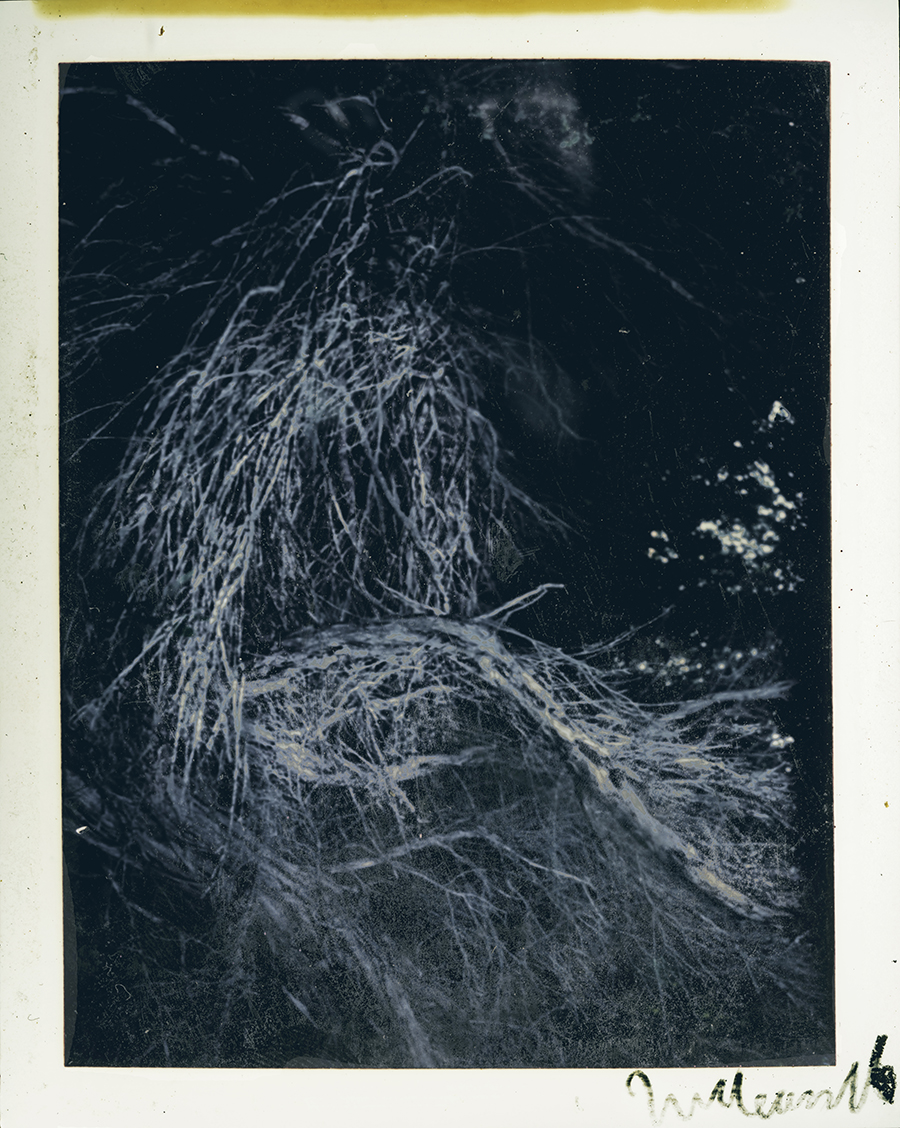

From the minutiae of the everyday to the sublimity of the natural world, Mclean Stephenson’s photography combines technical finesse, conceptual maturity and emotional depth.

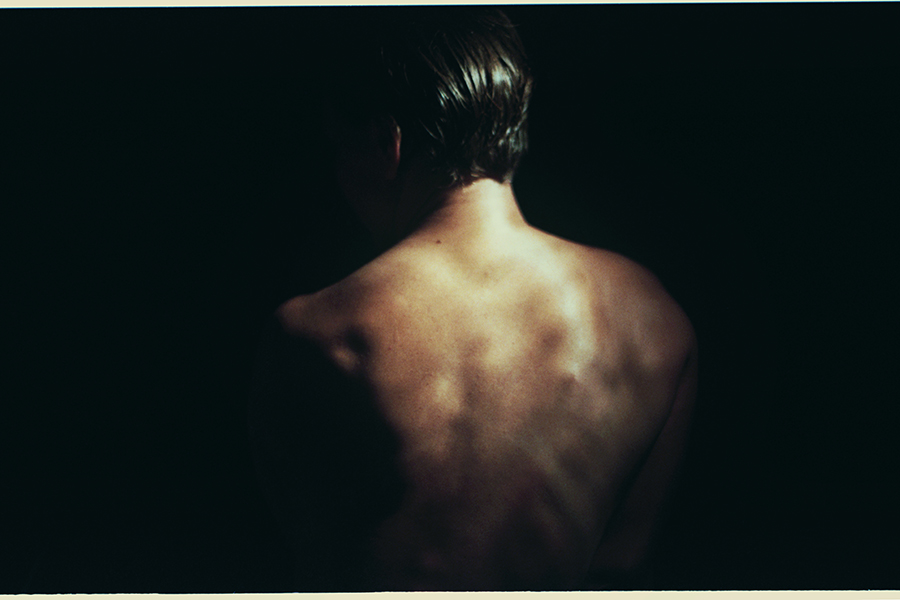

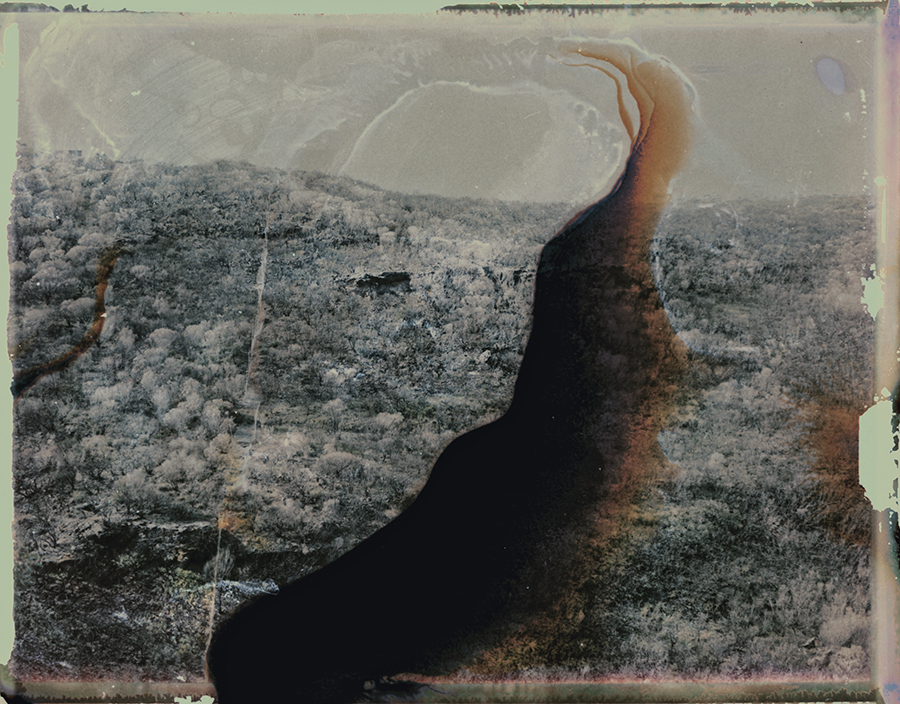

Weaving through impressionistic images of the natural world, to moments of rapture engendered by human nakedness, Stephenson’s work draws attention to the fabrication of photographic mediums while altogether illuminating realities that exist only between subject and technique.

This interview appears in Happy Mag Issue 6. Order your copy here.

“I don’t think these things should be easy. I think they should be earned.”

HAPPY: When did you first take an interest in photography?

MCLEAN: About 10 years ago I was given a camera as a gift. Before that I hadn’t thought much about photography.

HAPPY: You opt for monochrome photographs quite a lot, what do you prefer about black and white to natural-coloured photographs?

MCLEAN: Maybe half of my photos are black and white. The rest, colour. It’s not necessarily a preference, it’s generally about the subject and how I think it would be best represented. Having said that, I shoot everything on film, and a lot of the photographers I’ve been influenced by shoot on black and white film, so I have a certain fondness for it.

HAPPY: What does your technical process involve, to achieving these aesthetic outcomes?

MCLEAN: The technical process involves lot of time and money. I shoot all film, and lots of different film formats like 35mm, medium format, large format, all the polaroid types… I have a lot of different cameras for this, some of them are really old, a lot are modified in some way, a few are made from different camera parts. And then I have various different film development processes, chemical and otherwise. Many of the processes are born from mistakes that I then try to reproduce. I experiment a lot too. Like I might develop some film and then bury it for a few weeks and let microbes eat at the emulsion. Or I’ll carry negatives around in my pockets for a few weeks and let them fend for themselves. A lot of good photos don’t survive. But I like there to be a degree of uncertainty in the process; for chance to have a say. It’s a way for me to relinquish some of the control over how the image comes to life.

HAPPY: There’s a dreaminess to your abstract work; parts of your images are suffused in light, overexposed, bringing the viewer’s attention to the manufacture of a photograph. What are you trying to capture through this visual approach?

MCLEAN: This is a complex question. I think there are a few things at play here. Photography, as a medium, is capable of reproducing fairly accurate representations of the physical world. And technology is always pushing in this direction, creating new hyper resolution sensors and ultra sharp lenses that can render the minutiae of the physical world in exacting detail. The thing is, I’m not really interested in how well photography can reproduce the physical world, I’m interested in how it can transform it.

I manipulate light in different ways in order to transform the subject; to portray it in a different way; to remove it from one state and embalm it another. It’s like an act of coveting. I might see something in the world, something that would otherwise be overlooked, and photograph it in a way that draws attention to it, causing the viewer to consider it in ways they otherwise wouldn’t. Say I take a photo of some trees. If I do it well the viewer doesn’t just see trees, they see something that makes them feel a sense of yearning or mystery. That is the transformative potential of photography. That’s what I try and do. It’s hard, and I fail far more often than not, but if I can succeed once in a while it’s enough to keep me going.

Separately, I like to draw attention to the medium itself, to fact that the image is a photograph, which is essentially an abstraction, or a version of reality which, unlike the physical world, is flat, silent and specifically chosen. Which probably ties into my disregard for the idea of replicating reality. If there are imperfections in the image, like scratches, dust, fingerprints, I’ll leave them in.

HAPPY: Your 2015 book entitled Extracts Vol.1 is a rather broad surveying of life, decay, nakedness, vastness… what draws these subjects together?

MCLEAN: There isn’t a common denominator or underlying meaning that unites the themes and/or images. Nothing really draws them together. The collection was not put together like that and I don’t work like that. It’s common that photographers base a series on a single theme or idea. You’ll see a series of photos of people’s luggage, or albinos, or broken umbrellas on the side of the road, or rubbish or whatever. That approach leaves me cold. I don’t like the idea of making a body of work that explores a single idea and then, when you are finished, that’s it. The book goes on a shelf. The case is closed.

To my mind, if any single theme is worth exploring, it will continue to be worth exploring into the future. The themes that I explore, some of which you have noted, are still with me. They are still under investigation. And I don’t anticipate I’ll ever have the final say on nakedness or decay or any of the other themes that interest me, like unhomeliness, transgression or rapture. I’m not looking to make definitive statements either, I’m more about suggestions, hints, subtleties. I like to raise questions, not answer them.

HAPPY: Coronas 2015 (a naked photographer of Kirin J. Callinan) is as unashamed and candid as a portrait could get. What’s the story behind this photo? What was Kirin’s response when he knew you wanted to include it in a public collection?

MCLEAN: That was taken after a gig. Kirin was in the band area nude, drinking beer. That’s pretty normal for Kirin. I think he was also doing sit-ups. I took the photo, which is also pretty normal, I’ve taken countless nude photos of Kirin over the years. The first press shot I ever did for him 10 years ago was a nude. I don’t remember what Kirin’s response was to hanging the picture in the gallery. I doubt he had one. Remember that this is a guy who posts dick pics on Instagram. You know, I think his mum may have bought one.

HAPPY: You have a book coming out soon, could you tell us a little bit about the subject matter and aesthetic of this collection?

MCLEAN: In many ways, the new book follows on from the last one. The last book was too ambitious, it has more than 250 images in in. This book is more targeted in its subject areas, being landscapes from Australia and Asia and nudes. Most of the work is shot on large format polaroid, which is a lesser known form of instant film that requires a massive, heavy camera. It’s actually a real pain to work with, its inflexible and it provides completely unreliable results, which are qualities that attract me to it. I don’t think these things should be easy. I think they should be earned.

HAPPY: Describe your relationship with your camera.

MCLEAN: I have lots of cameras. For any shoot, I will have at least six. Sometimes more. They all serve different purposes. They all have different limitations too. I’m really rough on them. I push them really hard to get what I need. I wear them out. I tend to drop them on the ground when they run out of film and go looking for another one. I lose them. I’ve lost a lot of cameras. More than 20. I was recently in Japan for a week and I managed to accidentally smash one and drop one off a bridge. I’ve even expensed them into jobs.

I think of cameras as instruments or tools, as things I need to have to make the pictures I want. A necessity. Beyond that I don’t have much interest in them. They are hunks of metal and glass. I don’t remember them when they are gone or get sentimental about them. I remember the pictures. I get people contacting me with questions about cameras. I’d rather talk about their pictures. At the end of the day, the pictures are all that matter.

HAPPY: Are technically great photographs simultaneously emotionally rich ones?

MCLEAN: No, they aren’t, and sometimes it causes me a problem. I have a lot of processes and many of them are technical. Often, I will make a picture that achieves what I was aiming for technically, it might be in the tones or the manipulation of light, but it doesn’t have the magic. By which I mean it’s not a photo that does justice to the subject or is likely to elicit any response from a viewer. Occasionally I become emotionally attached to a photograph solely for its technical properties. Especially when a lot of work has gone into it. And I become blind to whether, beyond technical considerations, the photograph actually works.

Time tends to solve it. I put my pictures aside for a few months and then come back and look over them. It’s easier then to engage my bullshit detector. To say, “this works, this works, this is bullshit”. It’s an editing process. A process of refining.

HAPPY: In your experience, what is most detrimental to creativity?

MCLEAN: Security. A lot of artists fall into this trap where they begin repeating themselves in order to ensure that their work continues to sell, thereby ensuring their financial security. And this is often expected of them too – it’s what their representatives and investors want. So, it’s understandable – they need to make a living. Or an artist might start repeating themself in order to protect the security of their reputation. That happens a lot. The thing is, the process of making art requires that the artist is free to take risks, to flaunt conventions, to disregard the past, to be playful. Security doesn’t allow for these things. To security these things are anathema.

This answer is, of course, very specific to my experience, which is the experience of living in a relatively free liberal democracy. Art has other, more sinister enemies like, for example, state sponsored censorship. But that’s a whole other thing.

This interview appears in Happy Mag Issue 6. Order your copy here.