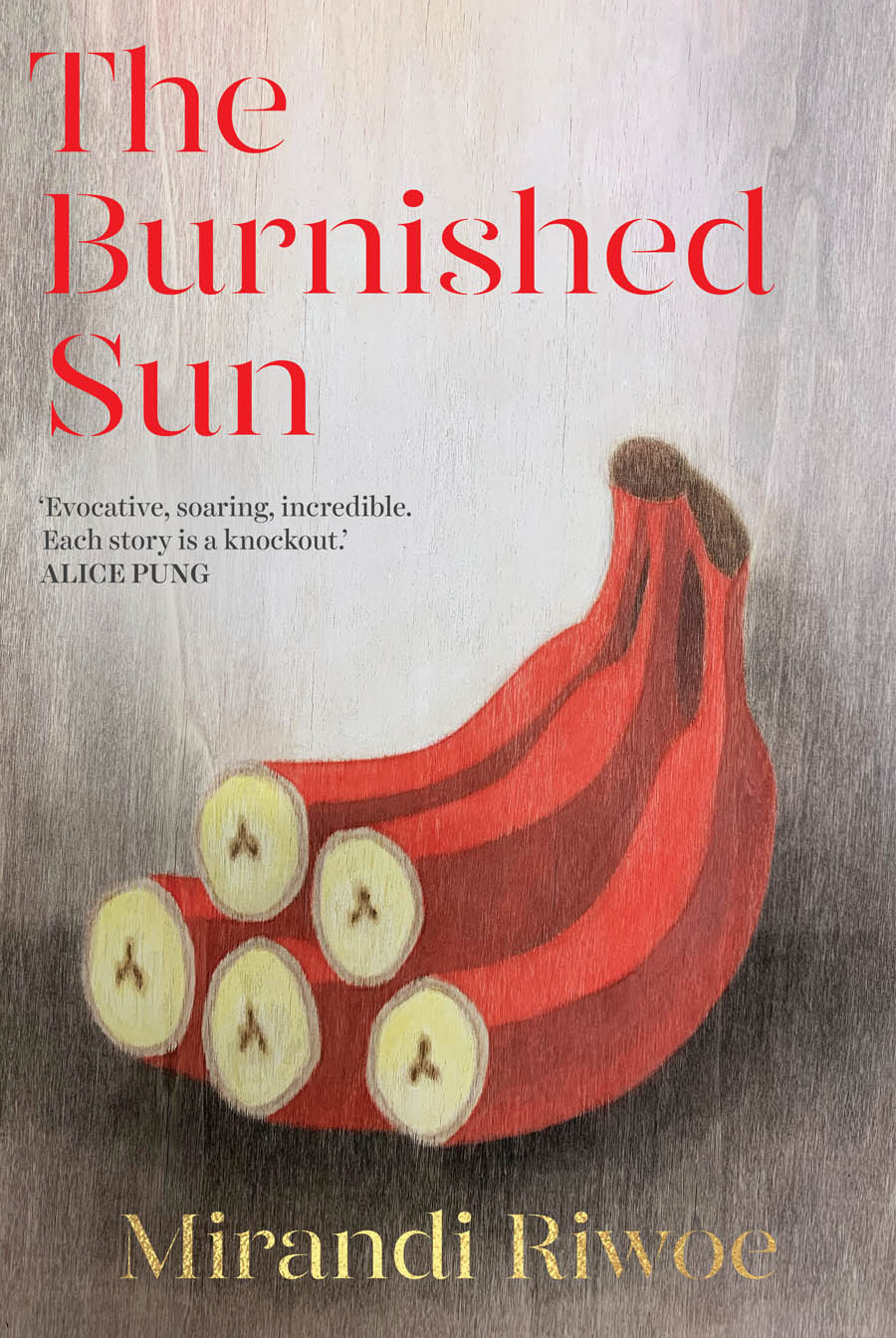

We caught up with award-winning author Mirandi Riwoe to chat about The Burnished Sun — a stunning collection of stories that feature cohesive themes viewed through multiple lenses.

The release of The Burnished Sun (UQP) brings together two award-winning novellas from Mirandi Riwoe — as well as a collection of short stories — in one volume. Its cumulative effect is mesmerising: with themes of displacement, yearning for connection, and the lingering aftermath of colonialism, being viewed through the eyes of a compelling cast of protagonists, in contemporary and historic contexts.

We caught up with Mirandi Riwoe in the midst of the launch tour for The Burnished Sun to chat about reimagining the past, bringing locations to life through the senses, and the joys of getting inside the minds of characters, including teenage boys.

HAPPY: The two longer novellas — Annah the Javanese and The Fish Girl — are reimaginings: one of the life and times of Paul Gauguin and the other a W Somerset Maugham story. How do your versions differ in perspective? And why bring these stories back to life?

MIRANDI: The Somerset Maugham short story [The Four Dutchmen] was written in the 1920s and is mostly about the four Dutchmen and what happened to them. The character of the Malay girl was just called a ‘Malay hussy’, or ‘Malay trollop’ — she’s on the periphery of the story but pivotal to it as well. My father’s Indonesian Chinese — so I identified with the girl — but I could also appreciate it from a contemporary feminist viewpoint. I was ticked off with the original version and wrote The Fish Girl from her point of view.

In Annah the Javanese, it was a similar experience, though she was a real person. There are photos of her and the painting of course. What we know of her is only what was said about her by white male artists of the time. They said she was exotic, she had a pet monkey, and when Gauguin broke his ankle, they said she cleaned him out. I did a lot of research into her life, but it’s not just about her perspective: it’s also about looking at the context and who we’re hearing from at the time. I wanted to offer other possibilities for each of their stories.

Why I wanted to tell these stories now is partly to do with airing a version that could be closer to what actually happened, but also the fact that women are still being trafficked. This kind of violence against women still happens.

HAPPY: The island of Java looms large in these tales too. Can you tell me about your connection to this place and why you brought it to the page?

MIRANDI: I found my way into fiction through my Eurasian background. My father came to Australia in the 1960s to study at university and we’ve always had a close connection with our Indonesian heritage. In the 1970s there was definitely a policy of assimilation and we didn’t speak the language at home, but we were still involved in the Indonesian community.

It wasn’t until I went to Griffith University that I learned the Indonesian language, then I spent six months in Yogyakarta in Java and learned more of the language. It’s been a big part of my life and therefore it turns up in my fiction.

HAPPY: In The Fish Girl, in particular, there are extraordinarily intimate sensory details. You evoke the place, but in every passage you also reveal how the characters interact with each other and their surroundings through touch, smell, and texture. Did that level of detail flow naturally as you were writing, or did you have to keep returning to it to etch in those fine details?

MIRANDI: The Fish Girl is one of the earlier pieces in this collection and the sensory detail came in the practice of writing it because I was writing of Java as I knew it. Mina [the protagonist from The Fish Girl] is a village girl and everything she sees and knows and experiences is in the context of that world. The senses were intrinsic to the story and the development of her character.

HAPPY: One particularly affecting short story was Dignity — which mirrors the larger novellas and their exploration of power imbalances, though in a modern microcosm. Did you find that sense of history repeating through the writing process?

MIRANDI: Someone was asking me once about how the themes link throughout the book. I think that’s probably to do with what I’m preoccupied with and what I’m interested in. A lot of the stories have to do with motherhood, feminist issues, and racism. Many of the short stories were reflections on what I was exploring in my life at the time.

For example, we have an Indonesian friend who works for my uncle in Java and he was really proud one day when we were there because his grandson had been born. My children were very young then. A couple of years later I heard that his daughter went overseas to work, because there wasn’t enough work in Java. I just felt terribly sad for her because she had to leave her toddler behind, while I had my children here with me. That’s how I first came to that story.

Then I did some research on the people who need to work and be servants overseas. Around the same time, the Indonesian president had recalled the servants from around the world because they weren’t being treated with dignity. It’s since changed again, because of course, people need money. That story had its origins in a personal experience that I then explored through fiction.

Had loads of fun at @newwritersfest Thank you for having me! Now, Hello Melbourne ♥️♥️ pic.twitter.com/Dh7v3TI1LP

— Mirandi (@m_riwoe) April 3, 2022

HAPPY: The thing I’ve always found thrilling about short stories is the way that entire universes can be compressed into ten pages, making a far greater impact than you thought possible in that short time it takes to read them. What attracts you to this form?

MIRANDI: As a writer, it’s quite immediate. If I’m thinking about something in my life — for example, the skateboarding story [Hardflip], which was fed to me through my son and his experiences — then I can immediately explore those ideas in a short story. Per word, you’re probably putting in more care and thought than you would in a novel. The words really need to work hard.

HAPPY: That actually reminds me of your story, Invitation. The details are so carefully and consistently drip-fed throughout, so within a page, you’re consumed by it. It’s like magic.

MIRANDI: Very difficult magic (laughs)!

HAPPY: Exactly! It’s such a fine craft.

MIRANDI: Yes, there’s no time to waste in short fiction. It’s really nice that you mention that story. My sister’s son has Fragile X syndrome. Before they found out that it was Fragile X, I guess it was treated like ADHD. It was heartbreaking when I heard him being referred to as ‘the naughty boy’ and the story just grew from that one idea.

On the other hand, a story like Invitation also forces you to look at yourself and reflect on periods in your life where you might’ve been more inclusive. The characters in Invitation aren’t nasty, it’s just life — and how everyone has their own stories and troubles.

Melbourne readers! We can't wait to see you tonight @ReadingsBooks Carlton to celebrate the launch of 'The Burnished Sun' by @m_riwoe.

Free, but registrations essential: https://t.co/Q8RQYjsyTt

— UQPBooks (@UQPbooks) April 4, 2022

HAPPY: There are themes that connect the stories — displacement, family connections that are stretched by distance, the ongoing repercussions of colonialism, and many more — but the voices of the narrators are so distinct and offer unique perspectives on all these themes. How challenging was it to inhabit the minds of these narrators? And were there any that stood out to you as being particularly memorable, or fun?

MIRANDI: I immerse myself into each short story for a long time before I actually write it. The one I’m probably fondest of is Hardflip. The story itself didn’t happen to my son, but some of the episodes reflect reality: being with two African Australian friends and not being allowed on the bus, for example. There are also aspects that are taken from the lives of some good friends that made it into the story too. There are touches to that story that I actually really like, which is a bit weird because it’s about a teenage boy (laughs) —

HAPPY: — and there’s more swearing in that one, so I guess it’s more fun.

MIRANDI: There would’ve been more swearing if I’d taken my son’s advice —

HAPPY: — (Laughs)

MIRANDI: But the other one I’m fond of — and which still makes me a bit sad — is Hazel [which is about a family attempting to connect with an elderly woman in a nursing home in the midst of Covid-19-enforced isolation].

HAPPY: It’s a very contemporary tale that many people can relate to right now.

MIRANDI: It is. When we were putting the collection together a year ago, we were discussing whether or not it will have dated too much. Then, of course, we had lockdown after lockdown, and even now, we have to be careful with nursing homes.

HAPPY: The stories are especially vital in the context of modern suburban Australia too. They present perspectives on the modern challenges of living in this country that the majority of Australians might not be aware of. What are you hoping that readers get out of these stories, if anything?

MIRANDI: At the end of the day, it’s probably empathy I’m hoping for and getting the readers to see a side of a story that they haven’t experienced themselves. But sometimes, like with Hardflip, it’s just pure annoyance and I want to point it out (laughs)!

The Burnished Sun is out now via UQP.