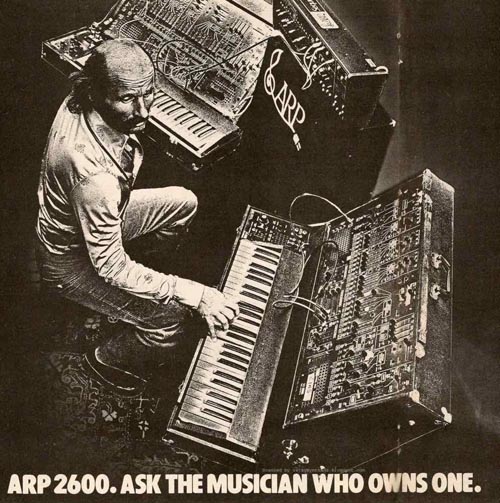

The ARP 2600 was the crowning achievement of Alan R. Pearlman’s synth journey. To this day, it’s prized for its thick analog tone and endless sonic potential.

The ARP 2600 came out of a purple patch in the history of American synthesis: the early 1970s. While its ostensible mission was to compete with the likes of Moog and Buchla, it also had another more humble and profound goal in mind: to take synthesis out of the lab and put it in the hands of musicians.

Don’t let its egalitarian ideals fool you though – it’s a professional-level machine, that’s capable of seriously inspiring sounds. Its legacy has led to many imitators in the software world, plus a forthcoming high-profile hardware clone.

Let’s dive into the history of this magical machine, whose legend continues to grow long after being phased out of production.

The Genesis

The late Alan R. Pearlman was a New York native and heavily imbued with entrepreneurial spirit. Before taking part in the synth race, he was involved in the space race, designing amplifiers for NASA’s Gemini and Apollo missions.

In the ’60s, he founded the Nexus Research Laboratory which manufactured analog modules and op amps – a successful company that was eventually bought out, giving Pearlman vital startup capital to fund his next grand project: ARP.

He kicked off ARP with $100,000 of his own money and with the help of investors in 1969 – which must’ve taken some nerve considering that this was the very beginnings of the synth industry.

The first cab off the rank was the 2500 model. It set the tone for the innovative semi-modular format, using a 10 x 10 matrix (a system that would go on to inspire modern instruments like the Arturia MatrixBrute) to create its patches.

While being a sonically superb machine, it’s learning curve proved to be quite steep and it wasn’t until the release of the 2600 that ARP tasted commercial success.

Streamlining the Workflow

Most synthesizers of this primordial period were custom-built and took some engineering expertise on the part of the player to get the most out of it.

Bucking the trend, the ARP 2600 continued the company’s predilection for semi-modular architecture, making it easier for players to create sounds straight off the bat.

Judging by the slew of recent releases that utilise this technique of patch creation, it left an impression on the minds of future synth designers.

Throughout its almost decade-long lifespan, the 2600 came in a variety of cosmetic guises, with minor changes to the internal electronics.

The first version, the ‘Blue Marvin’, featured bright blue aluminum construction and are now exceedingly rare, being garage-made with only about 25 being made.

When the 2600 shifted to factory construction, they settled on a grey enclosure, with the famous orange on black colour scheme emerging later in the ’70s with the 2601 model.

The ARP 2600 was competing against the other breakthrough keyboard synth of the era, the Minimoog – both three oscillator, monophonic synths.

ARP got into some legal trouble with their filters on the early versions of the 2600 due to their close resemblance to the classic Moog Ladder filter. But beyond a few characteristics, the ARP synth went on to carve its path through the golden age of analog synthesis.

Taking On Allcomers

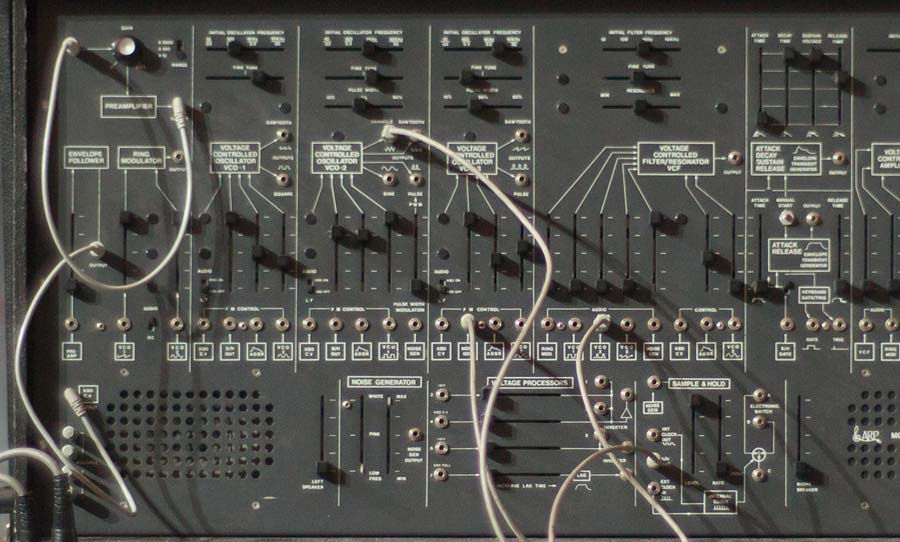

It has the look of a wall of modular synth modules, rather than the Minimoog’s desktop-style layout, with vertical sliders rather than knobs.

The pink noise, pulse variable, saw up, sine and white noise waveforms are spread across three oscillators, with two envelopes and a 24dB low-pass filter. There were also built-in speakers and spring reverb to create ambience around the sounds.

Aside from the classic analog circuitry, the layout of the synth ingeniously spoke to users at all levels. Where the 2500 was arcane and awkward, the 2600 was thoughtfully set out, approachable and easy to follow.

Beginners could be guided by the clear diagrams of the signal path and completely ignore the possibilities of external patching. Experts could patch to their heart’s content, redesigning the signal path to suit their own needs.

The synth was even designed for teaching. As the manual states, “All signal and control paths are indicated by arrows.”

It’s little surprise that a versatile and powerful analog monosynth like the 2600 had heavyweight support. Pop legend Stevie Wonder and jazz-fusion icon Joe Zawinul were early adopters.

As the years progressed and the synth phased out of production, electronic artists of the ’80s and ’90s like Joy Division, Orbital, Jean-Michel Jarre, Nine Inch Nails and more took up the mantle.

Interestingly, the synth’s sound design capabilities attracted the attention of Ben Burtt, voice actor and sound designer in the Star Wars series. The trademark blips and bloops of R2-D2? That’s right, combined with Burtt’s voice, the vocalising of this Star Wars favourite was created with the ARP 2600.

A Second Life

Though the impact of this instrument has been deep, it was commercially dwarfed by Moog and both companies were wiped out by innovative and more affordable synths from Japan in the early ’80s. Yet, like many rare analog classics, the 2600 has been given a second life in software form.

Arturia’s V Collection of classic synths, organs and electric pianos has a version of the 2600 that makes saving patches and creating extended sequences a breeze, while Alan Pearlman himself advised Way Out Ware on the development of the TimewARP 2600 – the only emulation that he endorsed.

In hardware, Behringer is slowly but surely working its way through the pantheon of analog synths and drum machines. They’ve at least hinted at a clone of the 2600, but details are still thin on the ground. Synthcube has taken a different route, offering kits to build your own.

It was a wild ride for Pearlman, with ARP ending in financial ruin in 1981. But in the intervening between the company’s collapse and his passing, he witnessed the continued evolution of his flagship instrument. And the story is not over yet.