The Man In Black was always one to champion the underdog. But Johnny Cash never made a bolder statement than At San Quentin.

On New Years Day 1959, Johnny Cash played his first-ever prison show at San Quentin. A frosty winter’s morning in San Francisco, Cash was not nervous about entering a maximum-security prison armed with one a guitar and his voice. Hell, San Quentin wasn’t even the most notorious prison in San Fran.

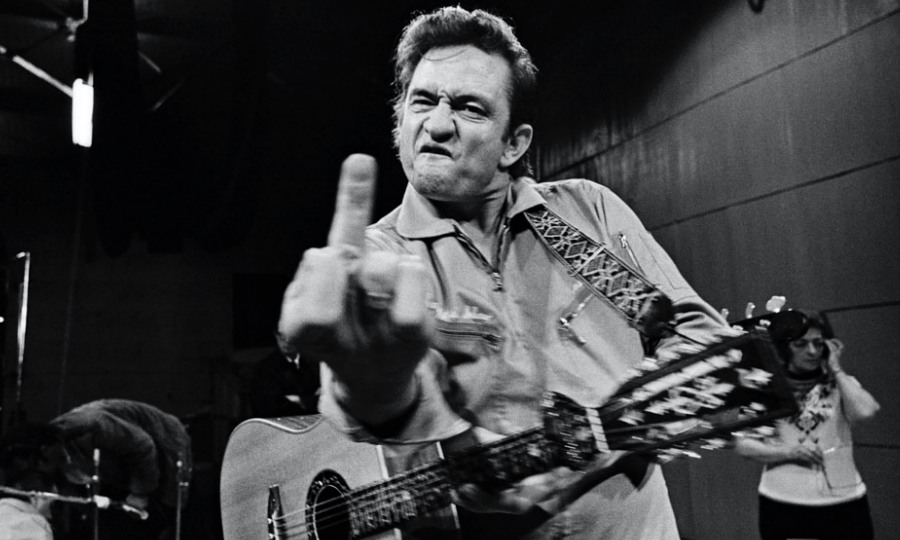

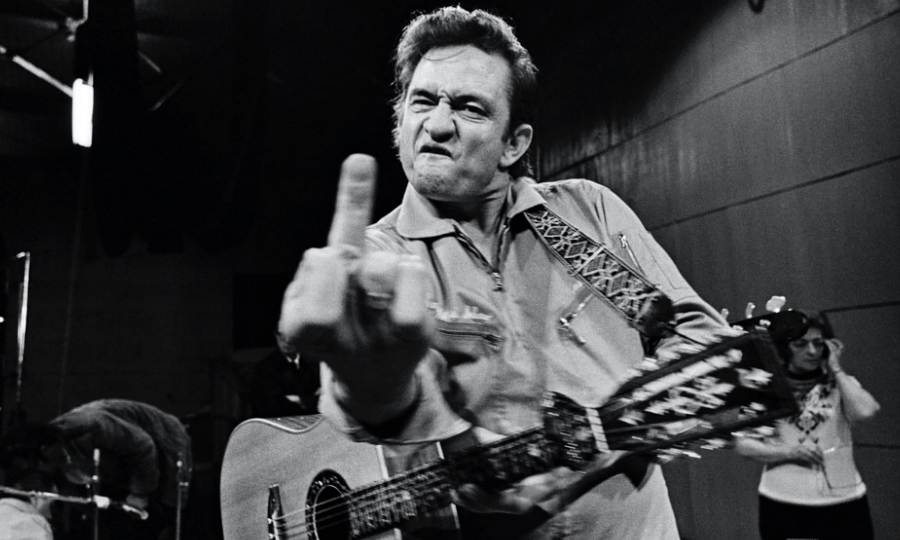

Aside from recording one of the most famous live albums of all time and taking one of the most iconic photos of all time, Johnny Cash inspired one unsuspecting inmate in the crowd that day who went on to become a country luminary in his own right: Merle Haggard.

Cash was arrested several times over course of his life but was never sentenced to prison. That being said he felt immense compassion for those who had made poor choices, as he himself had. As well as performing at prisons, always for free, Cash tirelessly campaigned for the rights of prisoners.

Folsom Prison Blues earned Johnny Cash his first Top 10 country hit in 1956, giving his fledgling career and critical jump start. The perspective of this song shaped the trajectory of Cash’s life and birthed the concept of some of the best selling live albums of all time. Johnny Cash remembers the forgotten men. Inside a prison, Cash sang like a croaky siren to those lost souls whose spirits were destroyed by the mindless penal system.

On New Years Day in 1959, Merle Haggard, who was serving 10 years for burglary, was in the crowd at San Quentin and cites the experience as a formative life-changing moment.

Haggard was a product of Bakersfield, California, a flea-bitten Central valley town which was the end of the line for tens of thousands of poor, white farmers who migrated west during the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s looking for work. These Oklahomans and Texans were colloquially referred to under the blanket term ‘Okies’ and brought with them a love of country music.

Merle Haggard would eventually become a draughtsman of the no-frills Bakersfield Sound, which shook the Nashville industry in the 1960s. But not before he got caught on the wrong side of the tracks and found himself at the mercy of the legal establishment.

On this fateful day, two of country music’s most revered outlaws crossed paths and set in motion the cogs that would change the genre forever.

In 1957, at the age of 18, Haggard was arrested on a burglary charge and sentenced to 15 years in San Quentin – yes, he turned 21 in prison.

“He had the right attitude,” Haggard later recalled. “He chewed gum, looked arrogant and flipped the bird to the guards — he did everything the prisoners wanted to do. He was a mean mother from the South who was there because he loved us. When he walked away, everyone in that place had become a Johnny Cash fan.”

Merle later confronted it as a guest on the ABC’s The Johnny Cash Show in August 1969. Earlier that year, Cash released his iconic At San Quentin, and encouraged Haggard to open up about his rough past and the autobiographical elements of his hit, Mama Tried.

Haggard: “Funny you mention that, Johnny.”

Cash: “What?”

Haggard: “San Quentin.”

Cash: “Why’s that?”

Haggard: “The first time I ever saw you perform, it was at San Quentin.”

Cash: “I don’t remember you being in that show, Merle.”

Haggard: “I was in the audience, Johnny.”

After that fateful performance, two major things happened. Johnny Cash made a career out of recording prison performances. And Merle Haggard was given the inspiration to launch a career after jail that resulted in 38 No.1 hits on the Country Charts, Sing Me Back Home, Okie From Muskogee and Today I Started Loving You Again.

Though that concert wasn’t recorded, Cash continued to tour prisons for the next ten years before recording At Folsom Prison in 1968. On February 24, 1969, recorded an incredible performance back at San Quentin. While Haggard was no longer in the audience, Cash gave the performance of a lifetime and took one of the most iconic photos in history. His photographer asked, “John, let’s do a shot for the warden.” The result is one of the most imitated poses of all time.

Opening the show with a new Dylan tune, Wanted Man sets the tone for his sermon to the sinners. Cash’s rapport is instant. I Walk The Line is presented as hard and tough as his storytelling is at its finest.

One of the only recordings of Starkville City Jail is found here, a comic retelling of a night he spent in custody. The inmates are on the edge of their seats, erupting into rapturous applause at ever knee-slapping quip or political jab at the system. Furthermore, Cash cuts a definitive take of the overtly Oedipal, A Boy Named Sue, a humorist tale by poet Shel Silverstein.

A tremendous double-take of San Quentin shows the incredible difference between both versions, before closing out the set with a brief, yet pounding rendition of Folsom Prison Blues.

“He always identified with the underdog,” says Cash’s younger brother, Tommy Cash. “He identified with the prisoners because many of them had served their sentences and had been rehabilitated in some cases but were still kept there the rest of their lives. He felt a great empathy with those people.”

The concert is over and those humans are still behind bars the following day, on the other side of the Bay. The immense connection and presence of that concert if something that has been imprinted on many listeners since. I defy a music star today to connect so deeply, and relatable, to the outcasts of society we have condemned to our dungeons.

While you’re here, check out Why It Mattered:

- Pink Floyd’s ‘Ummagumma’

- Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall’

- King Crimson’s ‘In The Court Of The Crimson King’

- David Bowie’s ‘David Bowie’

- David Bowie’s ‘Hunky Dory’

- The Grateful Dead’s ‘Live/Dead’

- The Allman Brothers Band’s self titled debut

- Led Zeppelin’s ‘Led Zeppelin II’

- Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’

- The Rolling Stones’ ‘Let It Bleed’

- The Clash’s ‘London Calling’

- AC/DC’s ‘High Voltage’

- The Doors’ ‘Morrison Hotel’

- Sigur Rós’ ‘Ágætis byrjun’