The London-based, Southern-born musician builds her sonic world from a foundation of photography and surrealist painting.

For singer-songwriter Brittney Jenkins, the artistic force behind Pisgah, inspiration is a deeply interdisciplinary pursuit.

Her forthcoming album, Faultlines, excavates personal and familial fractures, but its sonic landscape is vividly shaped by a cadre of visual artists.

Drawing from her M.A. in Art History, Jenkins channels the haunting entropy of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, which graces the album cover, the ghostly domestic erasures of Francesca Woodman, and the cinematic rural alienation of Gregory Crewdson.

These influences merge with her alt-country and goth-folk musical roots to create a record that is as much a gallery of poignant imagery as it is a collection of shimmering, propulsive songs.

Here, Jenkins guides us through the visual artists who helped define Faultlines.

Robert Smithson

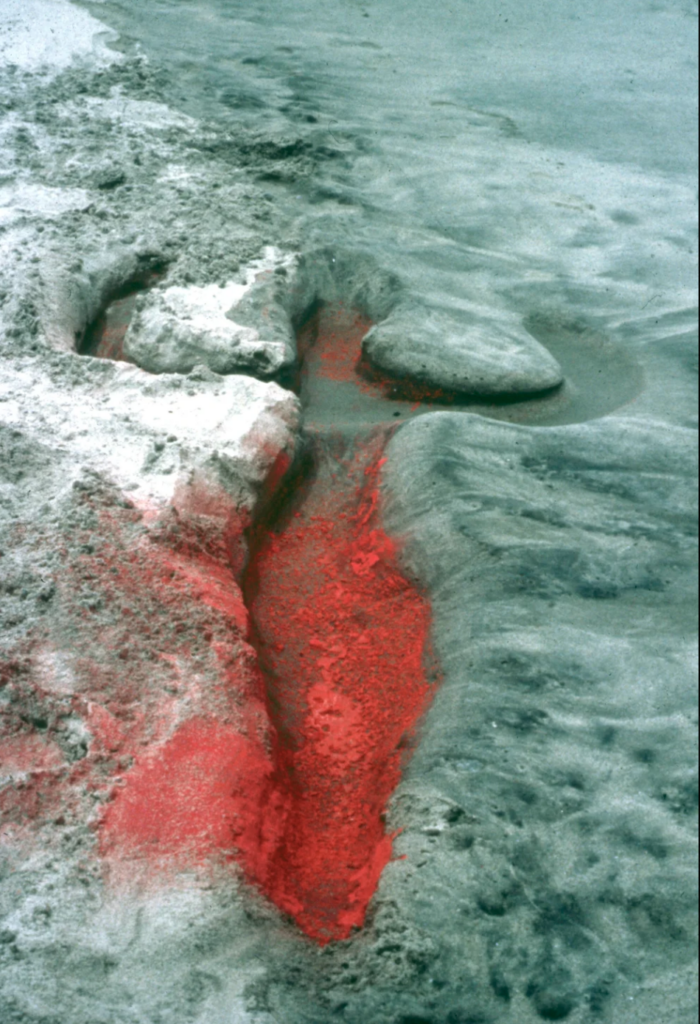

It feels right to start with Robert Smithson because the cover of the album is from the site of Spiral Jetty, his most famous art work. It’s a large-scale land art piece that’s located on the northern tip of the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

I’ve been obsessed with it since I was a young art history student, and I finally got to visit it this summer. The part of the Great Salt Lake it’s on is otherworldly and feels sacred, so I can understand why he was drawn to it when he was looking for a remote location for installation.

The work itself is about entropy, which is the idea that time and natural processes cause everything to dissolve into chaos and disorder. Entropy is a strong theme in the album so, while I wasn’t anticipating getting an album cover out of my visit to Spiral Jetty, I did. It was kismet.

Francesca Woodman

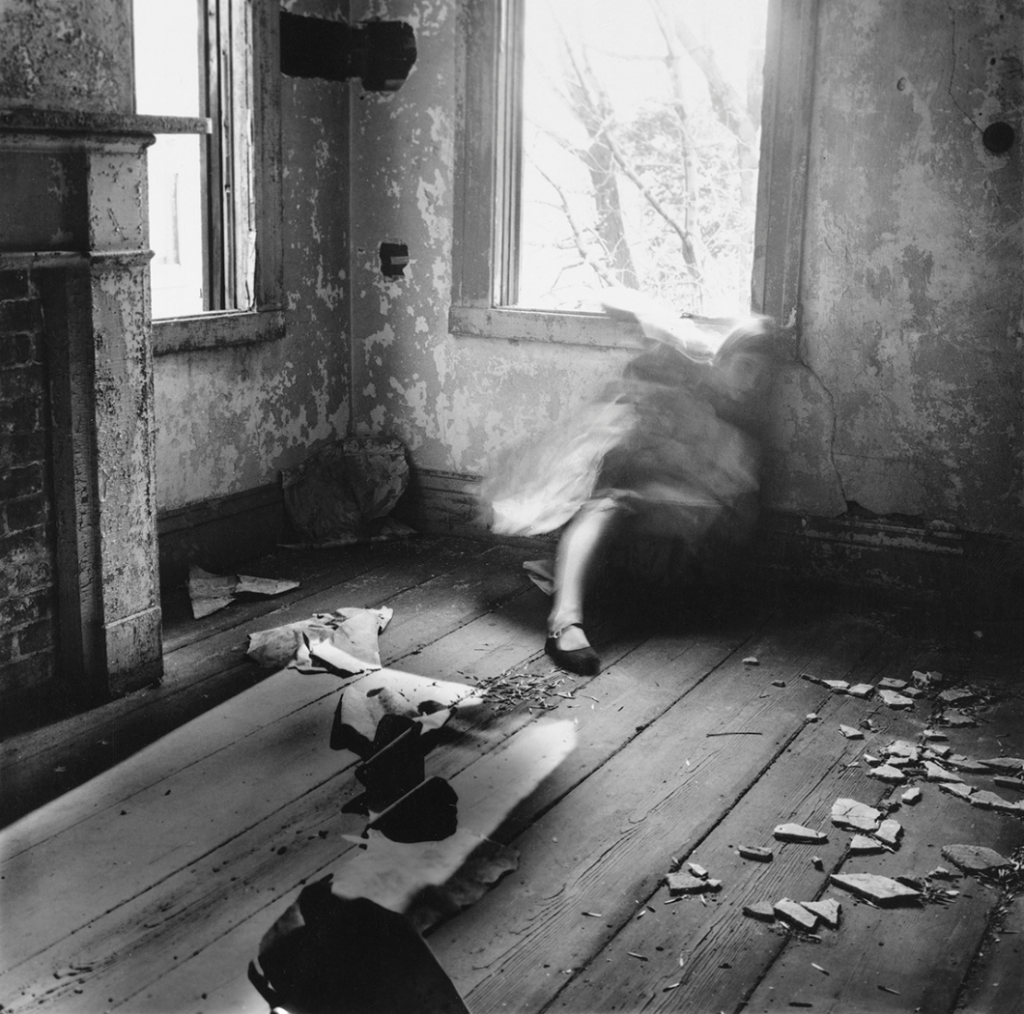

Francesca Woodman was an American photographer who captured some of the most phantom-like, surreal self-portraits I’ve ever found. She primarily used black-and-white film and her photos are often set in dilapidated domestic spaces that look like they haven’t been occupied in decades.

She’s always disappearing into the walls, hanging from doorframes in uncanny ways, and coming out of spaces you don’t expect. She’s one of my favourite photographers and, even though she died at 22, she left behind a substantial body of work that I never get tired of looking at.

Faultlines is so much about familial lineage dissolving and reshaping the boundaries of who I am, and the way she uses abandoned, chaotic domestic spaces in her work really resonates with that theme. The photo I always come back to is untitled, but it’s the one where she’s mid-movement, dissolving into ripped wallpaper in an abandoned house.

Gregory Crewdson

Oh, Gregory Crewdson. He’s one of my favourite living photographers and I discovered him very serendipitously. I was working for a cultural comms agency in London in 2018, and he had a show called ‘Cathedral of the Pines’ at The Photographer’s Gallery in Soho.

Frieze Week is amazing if you work for an arts/cultural organisation because you get free entry to everything, and that’s how I ended up at his exhibition! I didn’t know anything about him until then, and it completely blew me away. His photos are really cinematic, like an entire novel in one image.

There’s something so deeply American about them for me because they’re visual representations of broken dreams, discontentment, and the entropy (there’s that word again) in everyday life, particularly in rural areas like the part of North Carolina I grew up in.

It’s hard to choose a favourite, but there’s one photo called ‘The Shed’ from Cathedral of the Pines that I thought about a lot while I was making the record.

A woman stands in a sheer nightgown just outside the door of an old shed, hands covered in mud and looking down at the ground. It’s like she’s spent all night digging for something that she can’t remember now that the light of day has returned.

That’s often what it feels like to write songs for me, and what it felt like to write this record.

*trigger warning – discussion of sexual assault and violence

Anna Mendieta

I found out about Ana Mendieta through a book called Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency a few years ago, and honestly I couldn’t believe I hadn’t heard about her sooner.

She was a Cuban-American artist making brutal and beautiful feminist work about what it means to live in the world in a female body. In her photographs bodies become the natural landscape.

Sometimes we see them in the process of merging, and sometimes we only see the imprint they leave behind once the body’s faded completely from view.

In addition to her eco-feminist photography, she made some really unflinching works about the normalisation of sexual violence against women.

The most haunting, confrontational example is a work called ‘Untitled (Rape Scene)’ from 1973 that she made in response to the rape and murder of a young woman at University of Iowa where she was studying at the time.

I haven’t included an image of it because honestly it’s really painful to look at, but she posed as a semi-nude bloodied victim of sexual assault as a performance art piece for her fellow students and photographed it.

This particular image unfortunately reflects my own experience of being sexually assaulted, which I wrote about in ‘Bone to Pick’. I love her work because it forces us to look at brutality that we want to desperately look away from, and I want to embody her unflinching directness in my music.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard

I took a black-and-white film photography class in undergrad and found Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s ghostly photos when I was in that course. I’ve always been drawn to the ghostly and macabre (as you can probably tell by now), so I fell in love with his work immediately.

He lived and worked in Kentucky, also part of the American South, and captured the southern gothic so well. Like Francesca Woodman, he experimented a lot with slow shutter and capturing the movement of the figures and other phenomena in his photographs.

In his work his subjects often wear unsettling looking masks while holding strange props like dolls, dead birds, and rubber chickens.

The result is a surreal take on southern gothic, where the surroundings look familiar enough (especially for someone who grew up where I did) but become uncanny through his direction of the compositions.

There are a couple of his photos that I kept coming back to while I was making the album, the first an untitled image of a figure moving unnaturally in front of an old wooden sign and the second an image of two figures sitting in dark shadow in what appears to be an attic.

His work feels like capturing a dream, where everything’s just a little bit off, and that’s how I want my lyrics to feel – dreamlike, but revealing glimpses of truth.

Leonora Carrington

I wrote my master’s thesis about Leonora Carrington’s paintings, so she’s really special to me and has been a touchpoint in my life for many years now.

For those who don’t know her, she was a British artist who got involved with the Surrealists in Europe in the 1920s until she relocated to Mexico City during World War II, and she made some of the most layered, symbolic art works in the Surrealist movement.

She was born into a wealthy Irish-Catholic family but rejected her family’s pressure to conform to the societal standards for a young woman of her social class and became an artist instead.

She was a badass in the truest sense of the word, and through her lifetime made paintings, wrote novels and poems, and designed theatre sets and costumes.

Her paintings are populated with strange figures that are often anthropomorphic and seem to be conducting strange rituals, and they’re populated with mythic and occult symbols.

The painting I returned to as I was working on the album is called ‘And then we saw the daughter of the Minotaur’. I love this particular painting because, for me, it’s about what’s born from the violence and viciousness of generational trauma, and the way our family histories follow us.

It’s literal for the young minotaur robed in orange, a colour associated with the transformative power of fire, who sits at the table.

Yet despite her resemblance to the fearsome Minotaur from Greek mythology, she’s poised and regal as she welcomes two small children into her court.

There’s no sign of threat, but it looks like they’re about to be initiated into something really special. There’s so much more I could say about this painting, but I’ll finish with this.

It resonates with me so much because it makes me think about what it takes to find our way out of the labyrinth and into a truer version of ourselves, and that’s what the final song on the record (‘Song for Jason Molina (Cold Rain)’) is about.