From early experiments to modern electric-acoustic hybrids, the road to large-scale amplification for acoustic guitars has been a strange one indeed.

There’s really nothing like the warm chime of acoustic guitars. It’s a heartwarming sound that evokes the memory of learning your first few chords or playing songs by a glowing fire long ago. Sure it’s fun to blast your favourite electric through a fat stack, but acoustics will always be just a little more organic and wholesome, particularly in an intimate setting. But how about on the big stage?

Acoustics have always presented their own set of challenges when it comes to the live stage. It’s been a long road, but artists these days have a lot of luxuries compared to times gone by. Developments like pickups and direct inputs have made it a lot easier to project that beautiful acoustic sound to large audiences and high-tech hybrids such as Fender’s new Acoustasonic Telecaster show just how far technology has come.

So how did we get here? Well, let’s take a look at the history of acoustic guitars on the big stage.

Taking it to the Stage

Acoustic guitars have been around in one way or another for over 500 years. Early cousins to the guitar such as the lute and the mandolin had varying popularity throughout the classical era, but it’s only been in the last few hundred years that guitars received their modern tunings.

For much of the instrument’s life, it was considered by many as a ‘tavern instrument’, and to be fair it’s perfectly suited to that environment. A band of a few acoustic instruments could sit in the corner of a tavern, alehouse or village court and still be heard by the whole room.

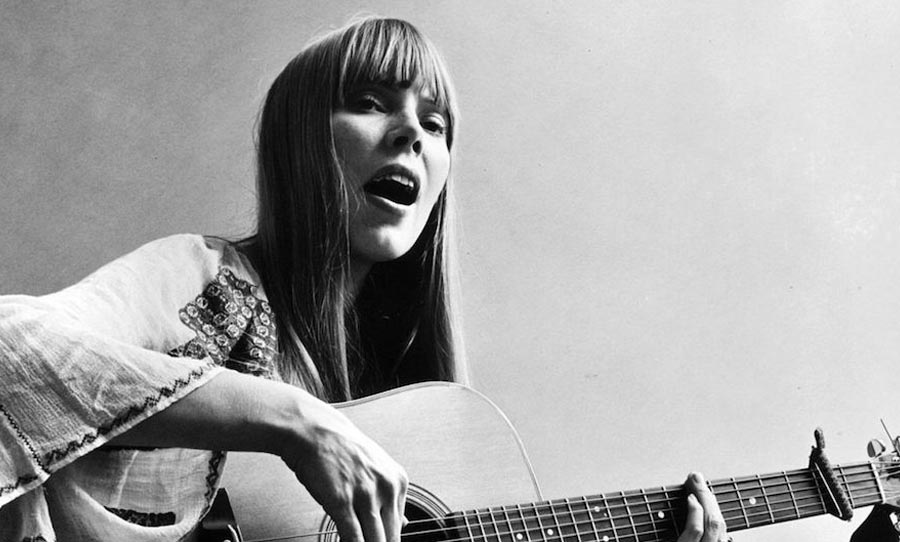

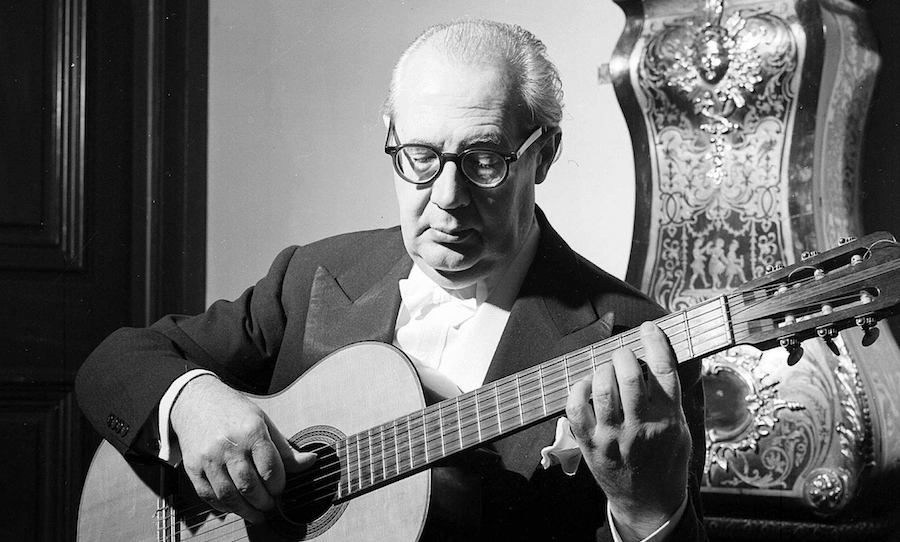

It wasn’t until the early 20th century when guitars began to enter the limelight that problems started to arise. Andres Segovia is largely credited for bringing the acoustic guitar to the big stage. Although volume capabilities were limited, the Spanish classical guitarist changed public perception of guitars through his extensive tours of Europe and the Americas in the 1920s.

”It is my great pride that I have brought the guitar out of the tavern and into the concert hall. Before, the piano was king, everybody played the piano, there were too many pianists,” said Segovia in an interview with the Tribune.

So the guitar had gained some respect as an on-stage instrument, but when it came to playing with larger companies, the acoustic guitar’s lack of volume was a challenge. An acoustic guitar in an ensemble had to compete with pianos, trumpets and violins, all of which were naturally much louder instruments.

Getting Louder

So what could be done to make acoustics more suitable for the big stage? Well, in 1927 John Dopyera invented the resonator guitar; an instrument designed to project enough volume to play alongside banjos and other instruments in the rhythm section.

The Selmer Guitar, developed by Selmer-Maccaferri in the early ’30s was a French variant of the resonating guitar, designed for classical applications. It went a long way to improve the acoustic guitar’s loudness issues in performance and it was the axe of choice of none other than Django Rhinehart.

Despite these improvements, it still wasn’t quite loud enough for big ensembles, I mean, try having a couple of trumpeters and a few enthusiastic sax players to compete with. So what then could be done elevate the guitar?

You may think the obvious response would be to ‘just mic it up’ as you would at an open mic night. And that would make sense, except at the time microphones and PA systems were still uncommon and in their infancy, and were mostly only used to project the voice in the prewar period. Of course, micing acoustics would become a common practice in years to come, but another technology was brewing that promised to solve the guitars woes once and for all.

Pickups

With the rise of jazz and blues, the guitar as an instrument was becoming more and more popular, prompting many frustrated players to try and find a way for themselves to be heard over a full band.

By the 1930s, the idea of electric guitars had been around for a while. Various patents from the early 1900s were filed and included clunky designs which used telephone transmitters placed inside violins and banjos. Other experiments used early carbon button microphones attached to a guitar’s bridge, which picked up vibrations but they had a pretty weak signal and didn’t take off.

George Beauchamp created the first working prototype of the electric guitar in 1931. He had been toying with the idea for some time and went on to manufacture the design with Adolf Rickenbacker later that year. George was an avid Hawaiian guitar fan, so naturally, his design used a lap-steel guitar that was fitted with an electromagnetic ‘horseshoe pickup’. The guitar used the vibration of strings over a coil of wire, wrapped around a magnet to ‘pick up’ the signal.

It looked like a frying pan, so that’s what they called it. The aluminium-bodied Rickenbacker Electro A-22 was the production version and hit the market, with a purpose-built amplifier sold alongside. It could be amplified, but it was a long way from the warm sound of an acoustic guitar.

Jazz Guitars

The frying pan was all well and good for Hawaiian and slide blues, but it wasn’t a super diverse instrument. In the 30s, Gibson designed their own pickup, and in 1936 placed a hexagonal pickup in the neck of the ES-150. Needless to say, it was a huge hit, especially in jazz ensembles where guitarists could take a more prominent role. It was made famous by the likes of Charlie Christian who cleared a new path for guitar soloists in jazz.

The distinct hexagonal pickup would even become to known as a Charlie Christian pickup. As a result jazz guitars soon became much more of a thing, especially from the 1940s onwards.

The Electric Acoustic

Another place the P90 pickup was fitted was in the neck of the Gibson J-160E, which is by many considered to be the first true electric acoustic guitar, an instrument popularised by a little old band called The Beatles. The pickup was mounted beneath the fingerboard of the dreadnought design, with tone controls on the top face, like an electric. It was manufactured all the way up to 1979.

The guitar didn’t sound particularly authentically ‘acoustic’, but it was a design that set the stage for the development of future acoustic guitars.

Martin tried to get in on the action in the late 1950s with their D-18E and D-28E, which offered two DeArmond pickups and three control knobs. Many consider these to be flops as the pickups had a strange effect on the tone, however, Kurt Cobain favoured the D-18E.

Refining Developments

By the 1960s microphone technology had caught up and many artists simply used a microphone pointed at the guitar for acoustic performances. The best placing for this was at the point where the neck and the body meet, however it could still result in a boxy mid-range and ‘boomy’ feedback issues. Amplifying the sound via pickups could produce a clearer sound without the worrisome feedback, but until the 1970s manufactures didn’t think to design pickups specifically for acoustic guitars.

Ovation made grounds with Piezo pickups that used crystals to produce electrical signals, but it was Takamine’s game-changing ‘palathetic’ design, that reinvented the acoustic pickup. It used six piezo transducers under the bridge plate, resulting in clear definition between the strings. So clear that it’s still the most common acoustic pickup design to this day.

These pickups were so sought after at the time that some guitarists went as far as to buy a Takamine with the sole purpose of removing the pickups. Takamine went on to pioneer the active acoustic, which had an onboard preamp and adjustable EQ controls.

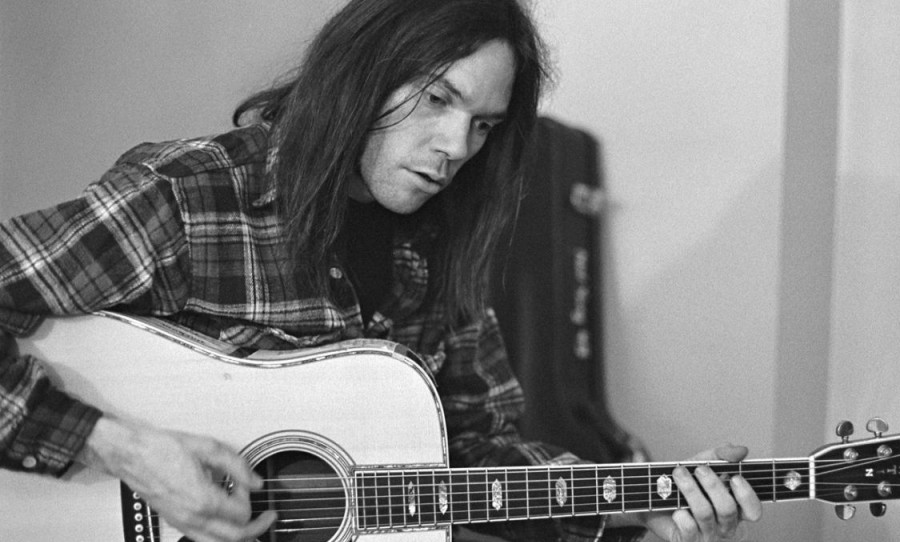

Some guitarists didn’t quite like the under saddle design and believed that palathetic pickups didn’t quite capture all of the sounds from an acoustics soundboard. The Barcus Berry pickup employed a soundboard transducer to scoop up the whole sound spectrum and similarly, the FRAP or Flat Audio Response Acoustic Pickup made famous by Neil Young used a unique stereo setup routed via a preamp

Towards the end of the 1980s, luthier Ken Donnell created a flexible gooseneck microphone that could be adjusted to the needs of many acoustic guitars. This design appeased those who still believe that microphones are the best way to pick up sound from an acoustic guitar.

Modern Tech and the Hybrids

In modern times, there are many options for microphones and pickups especially suited to acoustic guitars, however perhaps the most exciting of these are the designs that incorporate hybrid systems.

Amongst the most inspiring is Fender’s new Acoustasonic Telecaster, a design that uses a hollowed Telecaster body, however, it also uses a technology described as ‘Stringed Instrument Resonance System’. This high tech acoustic uses three different pickups, a Fishman Matrix Narrow pickup and ‘Acoustasonic Enhancer’ under the bridge, and a Fender noiseless pickup above. The guitar is able to blend each tone together and the result is 10 distinct voices, from classic acoustic tones to Fender electric tones and everything in between.

It’s an innovative design that shows just how far guitars have travelled and encourages daydreams of the crazy possibilities to come.

Find out more about Fender’s Acoustasonic Telecaster here.