From gospel’s fire to progressive rock’s grandiosity, Steiner paints a vivid picture of the forces that shaped Cave’s sonic universe with ‘Darker With The Dawn’

Forget mere biography, Adam Steiner‘s “Darker With The Dawn” plunges headfirst into the transformative crucible that forged Nick Cave.

It dissects the pivotal period that launched Cave from post-punk icon to one of music’s most revered poets. Steiner’s relentless pursuit of Cave’s self-analysis becomes a thrilling chase, unearthing the stories behind anthems like “Tupelo” and “Red Right Hand.”

This isn’t just a track-by-track analysis, though. It’s a tapestry woven with threads of biblical and literary influences, blues-soaked passion, and a profound understanding of Cave’s artistic evolution.

Whether you’re a fervent Cave devotee or simply a music enthusiast, “Darker With The Dawn” offers a laser-sharp, passionate exploration of a true artist. It’s a must-read for anyone who wants to witness the dawn of a legend, born from the darkest corners of self-examination. So, step inside, and let Steiner guide you with an exclusive extract of “Darker With The Dawn”, through the shadows to the light, where Cave’s music blazes like a beacon in the night.

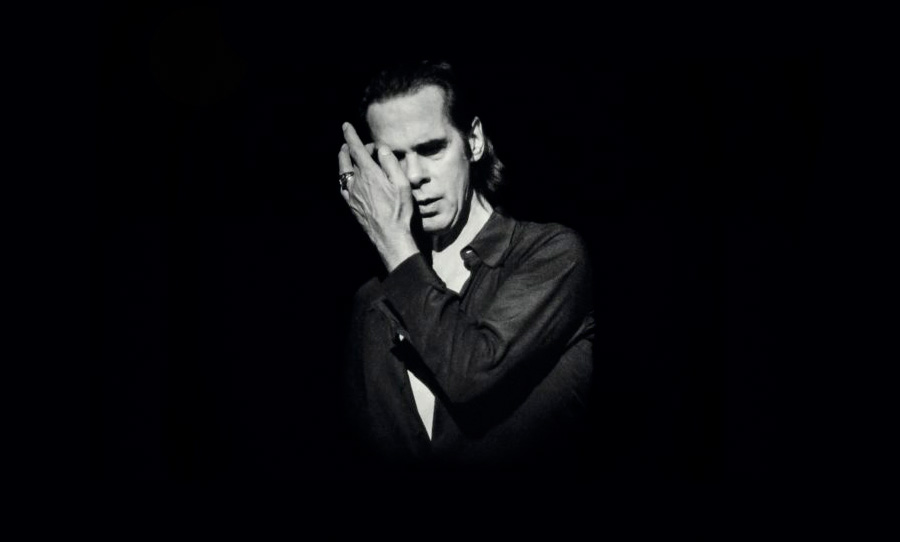

ROCK AND ROLL SAVIOR

Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds Find Triumph And Rebirth In The Wake Of Natural Disaster

A raging storm draws a thick curtain of black rain down upon the crooked and cracked land. Sweeping in across the horizon, water keeps on falling, the darkness only cracked by crooked spears of lightning and thunderous handclaps. A howling wind whips all along the skyline, bound inside the cyclone of a storm shot through with raindrop bullets, stretching time like a melting clock, beating into the merciless earth. In the stifled heartbeat of a repeating bass riff we hear a great rumbling terror move forward in its stuttering approach, every hiccupping second-third note breaking its terrible stride. The rivers have broken their banks, still waters are gathered to a rage, now nothing is here but the endless tide of the flood. Only Cave’s voice, full with both excitement and warning, breaks through the haze to guide us: “looky, looky yonder” at the skyline folding day into night. A sea of clouds bears down, smothering the land in leaden gloom, the electrified air swallowing up every last breath. The shadow of a great sweeping hand passes over the hearts of newborn twins, one stillborn, the other fighting for life, between them the wonder and the wrath of God as a moon-crowing chorus cries out the name of the forsaken place “Tupelo.”

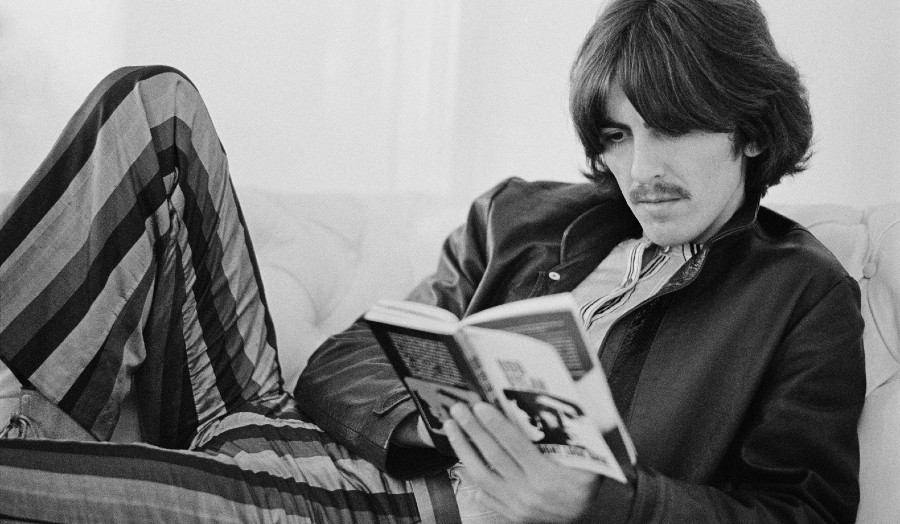

Endless rainfall opens The Bad Seeds’ second album The Firstborn Is Dead (1985) and falls throughout the song, as it does throughout so many of Cave’s songs. On “Tupelo” Cave invites the listener to bear witness to cataclysmic death and destruction wreaked by a natural disaster. We are dragged back to the southern town in deepest Mississippi, the birthplace of Elvis Aaron Presley in 1935—the new Jesus—brought into the world to fulfill his destiny as the future king of rock and roll, alongside his dead twin Jesse Garon Presley. Simultaneously his destiny reaches into the near future when a series of twelve tornadoes strike Tupelo on April 5, 1936, along with two days of flash floods that almost wiped out the town—all of which one-year-old Elvis survived. Cave collapses time where death, chaos, and creation are compressed into a singular frenzied moment.

Witnesses described the deluge as turning streets into rivers, telegraph poles are ripped out of the earth like sticks of corn from the fields, there are fires, and a rolling blackout descends on the town. The winds were so powerful that pine needles flew through the air and were embedded in trees like darting arrows. The simple clapboard house that Elvis’ father built for his family shook with the earth but remained standing, while others fell flat like they were built out of playing cards. The Gum Pond area of the town was all but destroyed, with several people hurled up into the air and dashed back down to earth so violently that their broken bodies were never recovered whole.

Cave compounds these events into his song, stretching the facts into myth as the flood of Tupelo carries with it echoes of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927—where the levees broke in 145 different places along the river, its nearest bend one hundred miles away from Tupelo.

More than 200,000 residents of the Mississippi Delta area were displaced and effectively exiled from their former home. Tens of thousands never returned, partly because there was nothing to go back to, but also due to the hostile racial climate of the time as displaced African-Americans needing relief were treated as unwanted immigrants in a foreign land. On the 1930 track “High Water Everywhere Part 1” Charley Patton sings of the refugee camps that flood victims were hustled into. Seeing the occupation of the moral high ground, he sings that it is not safe to leave for fear of being “barred,” meaning to be fenced in and put to work in camps.

The Bad Seeds’ “Tupelo” draws upon the more traditional blues song of John Lee Hooker’s “Tupelo,” recorded in 1959/1960, more than twenty years after the natural disaster had taken place. The song recounts the loss and devastation wreaked upon the small town, alongside nearby Gainesville. Hooker’s “Tupelo” keeps the story of the catastrophe alive and is delivered in memoriam to those who were no longer alive to tell it. With the line “What a mighty time” Hooker evokes the force of the Tupelo storm and tragic loss of human life that he had seen become a footnote to history. It also stands as a veiled reference to the shock and awe of (un)earthly powers to give and take away life within a single stroke. In the face of the tragedy Hooker discovers the cruel irony of faith; where God is either acting with terrible force or simply looking away, faith is no guarantee of salvation: “Could hear many people cryin’ “Lord, have mercy’ Cause you’re the only one that we can turn to.”

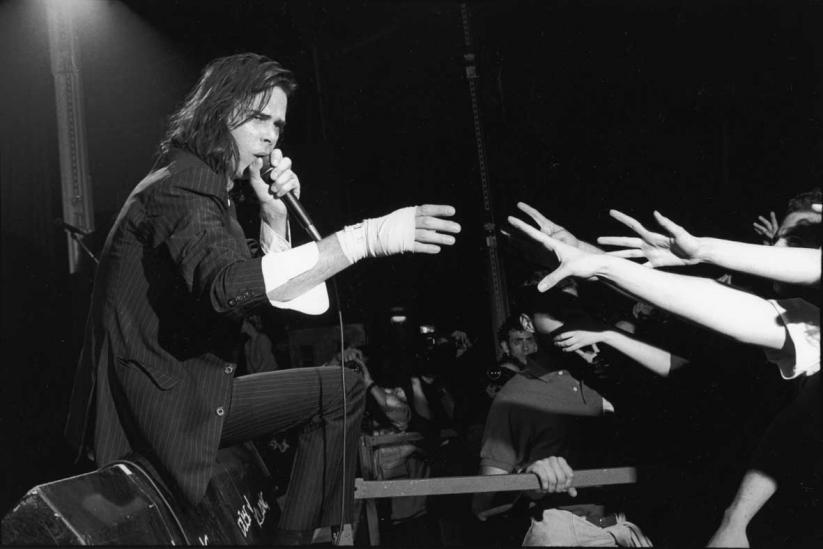

Live performances of “Tupelo” continue to expand into an unwieldy monster of sonic force overwhelming its creators. Cave’s tumbling words march the song forward, a deranged antenna struck by manic revelation. He dredges up the blues spirit amid a rising tide of bristling guitars and ominous smashing cymbals, only for The Bad Seeds to bring the whole edifice crashing down around them in great swells of tension and release. Amid this autodestruction the chorus spills into chaos as Warren Ellis holds his violin above his head toward the heavens like a lightning rod inviting a riotous squall of feedback.

“Tupelo” marks Elvis’ birth as musical messiah, announcing the second coming of the blues—crashing into the creation tale of Jesus Christ—both delivered as mankind’s savior only to be delivered and crucified as its sacrificial lamb.9 This is the starting point of rock and roll as a major cultural force, the breaking point at which populist music is electrified into the band format. Transcending grassroots jazz, rockabilly, and skiffle, it seemed to sweep away everything that had come before it. On the other hand, The Bad Seeds’ music becomes a dark funereal celebration for traditional rock and roll in the mid-1980s, just after The Birthday Party rode the wave of post-punk revolution. In all this confusion Cave managed to conjure forth the future while dredging up the bones of the past to create a terrific new present beyond the original innovators such as John Lee Hooker, with “Tupelo” straddling history as it blurred time.

“Tupelo” contains the lyric “the firstborn is dead,” referring to the symbolism of twin brothers, divided across life and death. It becomes the album’s title track, framing the songs that follow. There is also some inspiration from the Hebrew translation of the Bible where Jacob “moves on his brother’s heel,” raising the stark and primal image of a grasping hand of a child who tries to equal or usurp his own brother (Esau) so that he might live or simply to be the firstborn favored son. Elvis’ weaker twin becomes a sacrifice, accidentally martyred to deliver his brother who flourishes in his stead, solely drawing upon all of his mother’s love and strength.14 In Cave’s first novel, And the Ass Saw the Angel, the book’s mute protagonist Euchrid Eucrow grasps his brother’s heels and slides out after him from the womb. “With all the glory of an uninvited guest,” the second son tries to best the first. Cave regurgitates from “Tupelo” the image of Euchrid’s stillborn twin buried in a shoebox, with the added embellishment that it is tied with red ribbon a vivid streak of the umbilical cord’s mingled red, purple, and blue; blood into bruise.

In the many shoeboxes of Eucrow we find gathered toenail clippings, hair, and cicada shells in a grisly collection of body matter, like the locks of women’s hair nailed as scalps to the walls of Cave’s one-man box room in Berlin. These gathered remnants echo the significance of religious relics; as gory as they are increasingly absurd, the process of physical shedding exposes the precarity of the body, particularly when compared to the unbearable weight of the ephemeral soul, stripped of life into stillness. In “Tupelo” the shoebox as a flimsy cardboard coffin expresses both the fragility of the newborn corpse and the tragedy of the insubstantial pauper’s grave. The biblical power of “Tupelo” draws in part upon Presley’s own religious background, which deeply informed both his and Cave’s earliest music. Greil Marcus noted: “Even if Elvis’ South was filled with puritans, it was also filled with natural-born hedonists, and the same people were both.” Cave for his part could carry this duality with him. Presley was born into the stringent Calvinist sect of Christianity, but in the South, this manifested as powerful preachers, carrying the force of God in heart, body, and voice, to become the “faith of grace, apocalypse, and emotion.” There is a combined effect of sermon and gospel music performed upon the congregation-as-audience that Elvis would grow up among: “The preacher rolled fire down the pulpit, men and women rocked in their seats, bloodying their fingernails, scratching and clawing in a lust for absolute sanctification..It was a faith meant to transcend the grimy world that had called it up.”

Whether by accident or design The Firstborn Is Dead becomes a “Deep South concept album,” that in its most theatrical moments draws upon the heritage of classic Americana in all its span but still manages to subvert it to become something other, bending cultural history askew. By 1983 Cave had more or less relocated the band to Berlin, the last outpost of the “other” West in Europe—the entire enterprise became a work of will, imagination, and abiding love for the records of past America’s now distant time and place. Mick Harvey sees the album as a fragmented pastiche, an attempt to draw upon blues lineage but also to rise above it, becoming a postmodern tribute to authenticity itself. A transitional record bookended by “Tupelo” and “Blind Lemon Jefferson,” The Firstborn Is Dead combines Cave and The Bad Seeds’ earliest musical influences with the perspective of the band they would become, dissecting the connective tissue from which they would continue to evolve, seeing their sound deepen and broaden with each new album. Tennessee Williams said that “the South” was a construct of the popular imagination; there was no such place beyond the art that helped create it, mythic truths that would later transcend it. The power of the blues draws upon the nascent energy of the land and its history, reified in the Southern Gothic tradition that haunted the shadow narrative of Elvis Presley. In isolation Tupelo is hardly an auspicious place, but it expresses the musical culture he grew up in. Born on the wrong side of the tracks, Presley was raised in the poorest part of town alongside the black community. In an era of Jim Crow laws, which even after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1865 had brought about the abolition of slavery, enforced a psychic barrier of difference and alien territory between white and black neighborhoods, ghettoized by physical and mental barriers. The situation of his humble background exposed Presley to both gospel and blues music, and the roots of these musics in “spirituals” that would likely have been sung by the enslaved ancestors of his neighbors only a generation before.

Gospel drew uniquely upon the religious vernacular, the songs rooted in Christian narratives of deliverance and salvation, the struggle in a world of sin that found real-life counterparts for biblical characters. In his first book of autobiography, former slave and later abolitionist orator Frederick Douglass claimed the spirituals as folk songs and that they were the true testament against slavery: “They were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish . . . a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.” Douglass’ description seems to prefigure the spirit that blues music would become: “The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.” In order not to drown in their pain, the singer must rise above it.

The push and pull of deliverance and self-abnegation were also present in Cave’s music, alongside the glorious troubles of the blues singing tribute to “the joys and the pain of the world of flesh.” From the more comfortable white perspective he was able to cross over into the more metaphysical realm of spiritual deliverance from evil and wrestle with the rules and societal strictures of biblical moral codes. With so much of his music Cave reached for tenderness and insight while throwing the kitchen sink of biblical narrative along with it. Southern spirituals and gospel would transmute into the blues, thought to have originated in Mississippi or Alabama sometime after 1860, marking a divide that reflected the two sides of the black experience like a flipped coin. The “pre-freedom longing for escape” was an expression of pain, suffering, and hope of people “living in bodies that did not belong to them,” cast between heaven and earth with the blues expressing “the post-freedom realities of day-to-day life,” realizing a new baptism of fire. If slavery is punishment without crime, then life beyond the plantation becomes further time served in a hostile and unwelcoming world.

The blues sparked rock and roll’s native sensuality to become an “affective freedom” of real needs, loves, and desires that were “denied them in slavery and dismissed in freedom.” The blues was a language that transcended situation, with universal sentiments that could not be denied by the hardest of hearts. Numerous examples feature in Cave’s discography. “The Witness Song” from The Good Son (1990) draws upon the gospel song “Who Will be a Witness?” Elsewhere, The Bad Seeds’ chilling cover of “Hey Joe” stands apart from the original blues and Jimi Hendrix’s more famous choppy and fluid guitar. Cave and his band hammer the song home into an eerie drone, more dread-dirge than psychedelic dream. Cave’s “City of Refuge” was based upon a blues standard that carries echoes of the history of fleeing slaves. The Bad Seeds’ wild-with-fear version has him running blind in a sandstorm, knowing that wherever you go, you take your problems with you. Howlin’ Wolf reframes the scenario on his 1966 performance of “Down in the Bottom”: “When you see me runnin’ / you know my life is at stake.” The song tells the story of a young lover escaping from his partner’s “old man,” perhaps to avoid a shotgun wedding, but it is the narrative of running, from the law or social authority, that Cave made the returning race in his songs. Perhaps when Howlin’ Wolf sings it, he’s carrying the echo of his ancestors’ inherited trauma running from slave masters, the constant threat of the lynch mob, and away from America.

Fundamentally the blues are about “survival [or not] on the meanest, most gut level of human existence.” This “meanness” has double meaning, reading as literal cruelty or lack of kindness, being done to, or by, the singer—raw and real. This hard-bitten (and hard-won) knowledge that could come across as sour, bitter, and angry, alongside the expression of deeper passions, the blues was sometimes considered in deviant opposition to gospel and spirituals. These evocations of struggle fed into Cave’s listening experience, softening and hardening his musical and emotional ear.

This bleeds into the mythologizing of Robert Johnson and his early death in 1938 at age twenty-seven and the legend that he sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads, standing as one of stations of the cross where sin meets the possibility of salvation. Johnson makes his choice (or is chosen) to become a great guitar player, never looking back to see what might have been lost in the exchange. He would be murdered at the hands of a jealous husband, or so the legend goes. Johnson’s confrontation with the blues becomes a kind of inner struggle, urgent and overwhelming. He sounds more like an addict than a prophet when he sings: “The blues, is a low-down achin’ heart disease/Like consumption, killing me by degrees.”

In the ghostly songs that emerged in his wake, Johnson becomes both doom-bringer and emotional emancipator, his devotion to music claiming him as a martyred saint. His and Cave’s paths would cross again on the lyrical and thematic visitation of 2013’s “Higgs Boson Blues,” where Cave cannot decide whether Johnson or the Devil came off with the better part of the deal of revelation renewed. Cave would end The Firstborn Is Dead with “Blind Lemon Jefferson”—a contemporary of Johnson and Leadbelly—one many young black men crowned and condemned as the nascent king of the blues who would die young, aged thirty-six. Cave explained that he did not have much interest in the musician himself, more what he represented: the notion of paying your dues, as presented in the trials and tribulations of blues music.

A timeless Bad Seeds track, “Tupelo” looms tall as the self-made myth that confirms Cave as both postpunk heretic and rock and roll redeemer. Offering a conjoined vision of past and present, it declares the band’s future mission to save the contemporary music scene of the mid-1980s from itself by resurrecting the vitality of rock in a new language. “Tupelo” marks the moment The Bad Seeds became a band apart from the mainstream, continuing to pay warped tribute to the blues bound over to legend, tradition, and creative renewal—as they trashed, junked, and scrapped sound to remake the music of the past in their own image.

Adam Steiner is the author of Darker With The Dawn — Nick Cave’s Songs Of Love And Death.

Check out Darker With The Dawn here.

Connect with Adam Steiner on Instagram, and find out more here.