Chick Corea was a true musical scientist, exploring the limits of creativity and achieving the nuclear breakthrough of fusion jazz.

Chick Corea’s long career of musical innovation fairly earned him worldwide recognition. And if the is such a thing as universal respect, he earned it. Alongside his good friend and fellow pianist Herbie Hancock, he pioneered jazz fusion as a genre and twisted traditional musical conventions, transforming the way music was written, performed and consumed.

A massive 65 nominations make Chick Corea the fourth-most nominated artist in the history of the Grammys, 20 of which he won. While he passed away in early 2021, he has left a legacy as one of the most influential and groundbreaking jazz musicians of all time, alongside an extensive discography that showed him dipping his toes in almost every genre imaginable. This is the story of musical legend, Chick Corea.

The jazz juvenile

Chick Corea was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts in 1941, and was quickly immersed in the world of music. His father, a Dixieland style trumpet player, had Chick playing piano by the age of four, and drums by the age of eight. Already he had been consumed by the art of jazz, with early influences including Horace Silver and Bud Powell, jazz pianists who played a role in the growth of bop and swing music. Outside of playing in his high school drum and bugle corp, Chick Corea began playing his own jazz gigs, and after a brief stint studying at Juilliard, he began dedicating his time in pursuit of a career in jazz.

By the early 1960s, Chick Corea had begun playing in numerous different groups, including under Latin bandleader’s Mongo Santamaria and Willie Bobo, as well as some smaller jazz bands such as Blue Mitchell. In 1966, Chick Corea made his recording debut as a band-leader with Tones for Joan’s Bones, and in 1968, alongside Roy Haynes and Miroslav Vitous, he released Now He Sings, Now He Sobs. This was the first true exhibition of Chick Corea as an improvisational wizard. The album quickly became a jazz classic and in 1999 was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

The late 1960s was a pivotal time for Chick Corea’s career. From 1968 to 1970, he joined up with Miles Davis’s group, replacing his future friend and fellow musical pioneer Herbie Hancock. Miles Davis was transitioning towards jazz fusion at the time, and by convincing Chick Corea to begin playing electric piano, set events in motion that would change the future of the genre. During his time with Miles Davis, Corea helped to record numerous records, including Filles de Kilimanjaro and the infamous Bitches Brew. His transition to the use of electric instruments would stay with him for the rest of his career and allowed him to carve a path in the musical climate for several decades.

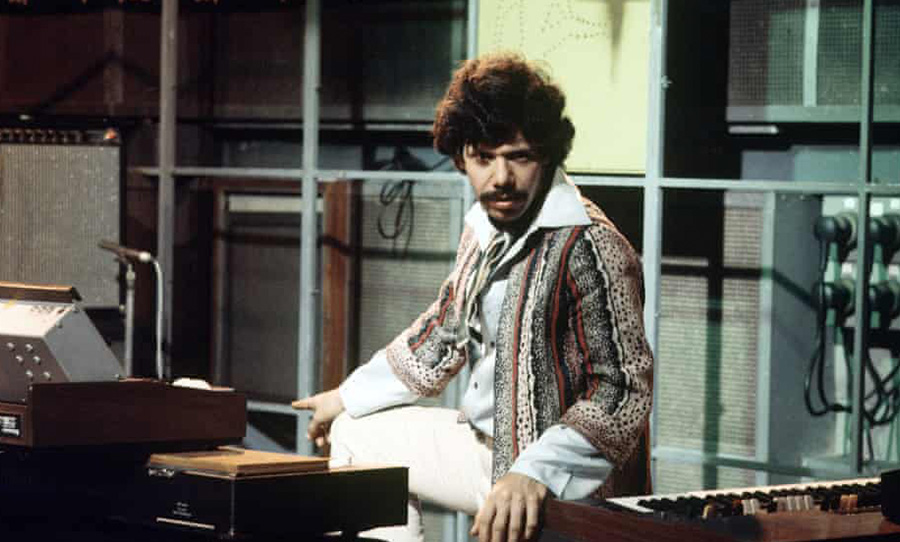

Photo: Getty Images

Returning to forever

In 1971, after continuing to build a reputation playing with Stan Getz and Circle, Chick Corea formed his own group Return to Forever. The group was made up of bassist Stanley Clarke, percussionist Airto Moreira, sax player Joe Farell and vocalist Flora Plume, and originally drew on Corea’s Latin and Brazillian influences. Return to Forever burst into the world in 1972 with their self-titled debut, which made it to number 8 on the Billboard jazz charts and earned Chick Corea his first two Grammy nominations.

Making use of what he had learned during his time with Miles Davis, Chick Corea began sculpting Return to Forever into an act focused on pushing the boundaries of jazz fusion. Less than a year after their first release, the group introduced drummer Lenny White and guitarist Bill Connors, and in 1973, released Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy. This album saw Corea delve deeper into the use of electronic instruments and sounds, melding prog and jazz together in a marriage of accented hits and changing time signatures. The album’s eponymous track provides a snapshot into the change that the group had rapidly undergone, with a wild heavy progressive rock sound, injected with the subtleties and nuances of jazz. Chick Corea was crafting a genre that was unlike anything that had been heard before.

In 1978, 2 years long after releasing their best-selling album Romantic Warrior, Return to Forever disbanded. Despite a short half-decade lifespan, the band had changed the very concept of what jazz was and set a precedent for the transformation and marriage of various genres.

The era of The Elektric

The next decade saw Corea continue to further his craft, working with artists such as Herbie Hancock and Thelonius Monk, until 1985, when he formed Chick Corea and The Elektrik Band. Featuring bassist John Patitucci, drummer Dave Weckl, and Australian guitarist Frank Gambale, The Elektric Band was designed with the pure intention of defining and developing the genre of jazz fusion. While the band’s lineup changed several times throughout its lifespan, The Elektric Band remained active until 2017. In a similar way to Return to Forever, the band released a self-titled debut album that set the tone of the band’s intentions.

Alongside performing with his new group, Chick Corea spent lots of time creating music and collaborating with other musicians, including his ensemble Change in 1999 and several solo piano records in the early 21st century.

Never slowing down

Up until his passing in February of 2021, Chick Corea remained active with an enthusiastic drive to continually sculpt every genre he touched. There are few people that have singlehandedly shaped music to the degree Chick Corea has, with his massive discography demonstrating his true passion for carving away at the walls of musical convention.

Having worked with some of the biggest names in music, such as Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and Steve Gadd, and influencing them in the process, Chick Corea has truly earned himself the title of a musical titan, doing what he did purely because it was his true love. At the news of his death, Herbie Hancock shared an insight on what Chick Corea was really like as both a musician and as a person:

“Chick was always playful; there was this kind of joy in his playing, and almost a childlike playfulness, like we’re playing in a sandbox, and it brought joy to me and then I would feed something and it would bring joy to him. We were like two kids. That was so inspiring and encouraging. There was never one hint of competition; it was all inspiration. So I could get inspiration from two [places]: I could get it from myself and from him. And I think he felt the same way.”