“You canny bastard. You’re writing a farewell album.” *

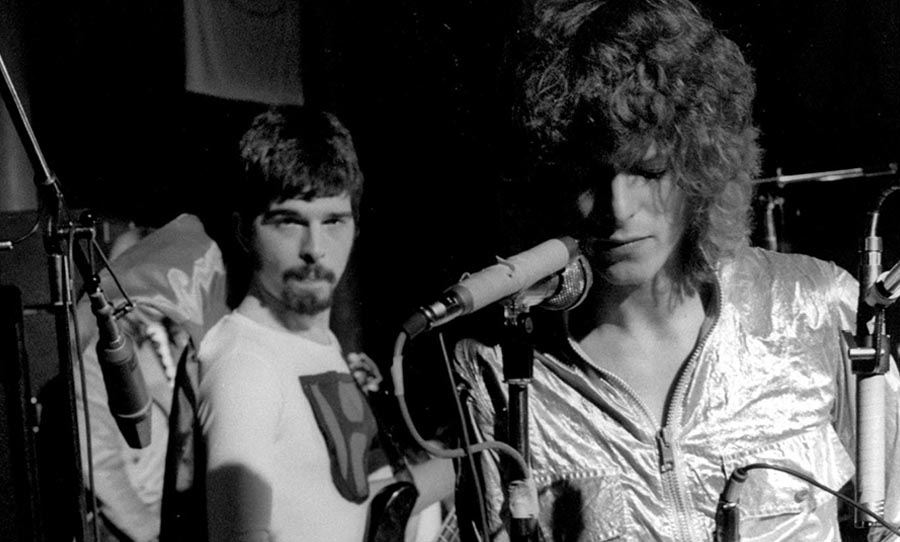

Tony Visconti started strumming the ukulele at age five, playing the bass guitar in his early teens, and writing arrangements when you could barely call him an adult. That’s when a British record producer caught wind of his talent and offered him some production work. Visconti moved from Brooklyn to London in April 1967. He was 22 years old.

Meanwhile, David Bowie had just released his first solo LP, slated as “an amalgam of pop, psychedelia, and music hall.” The record failed to chart. Bowie was 20 years old, very broke, and mostly unsuccessful. His song publisher arranged a meeting with a young American producer/bass player who had recently immigrated to the UK, thinking the two might hit it off and develop a mutually-beneficial relationship. Before the day ended, Bowie and Visconti had spent hours discussing Andy Warhol and underground American music, taken a long stroll down Oxford street, and wandered into a Roman Polanski film.

There were few artist/producer relationships closer than David Bowie and Tony Visconti. From Space Oddity to Blackstar – it was an epic, cosmic friendship until the final days.

Over the next forty-plus years the pair would collaborate on dozens of recordings, including Bowie’s second album (1969’s Space Oddity) and its 1971 follow-up, The Man Who Sold The World. Sometimes Visconti produced, sometimes he played bass or other instruments, sometimes he sang backing vocals. But success was not immediate, so sometimes Bowie did it without him.

After Bowie’s two Visconti-produced albums received mixed results, the two decided to call it quits. “Nobody was buying those records,” Visconti told Paul Du Noyer in 2012, “And much as I loved him artistically, we’re in the business of selling records. You don’t get invited back to the studio unless you show some returns for it.”

Their friendship remained strong and Bowie asked Visconti to come back and produce Young Americans, released in 1975. Highlights from that album included the title track (what Bowie described as “a predicament of two newlyweds”), a cover of The Beatles’ Across the Universe (featuring vocal work from John Lennon himself), and Fame, which became Bowie’s biggest hit to that point in the United States – his first number one single on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. Visconti would go on to produce and co-produce dozens of recordings for Bowie for the rest of Bowie’s life.

“He’s always been very trusting of me and we don’t have to have a great conversation before we do each album,” Visconti said to Du Noyer. “He states what he’d like to do, and because we share a wide range of interests, he only has to say ‘I’d like to go to Philadelphia and make an R&B album’ and I say ‘I’m right there, buddy, just let me pack my case.’”

Bowie started keeping a lower profile in the mid-2000s and it fell to his friend and colleague to serve as Bowie’s unofficial mouthpiece.

“I don’t know why he’s been so quiet,” Visconti said in a 2013 interview with The New York Times Magazine promoting The Next Day, Bowie’s 24th studio album. Bowie was doing fewer shows, making fewer appearances, and avoiding interviews altogether. A 2006 New York charity event ended up being Bowie’s final public performance. “People would say to me, ‘He’s dying, isn’t he?’ with a tremble in their voice. I’d say, ‘If he’s dying, he’s the best looking dying man I’ve ever seen in my life.’”

Visconti produced Bowie’s final two albums. They recorded The Next Day in total secrecy. Visconti said it was not hard to conceal its existence from the public. If someone asked, he lied.

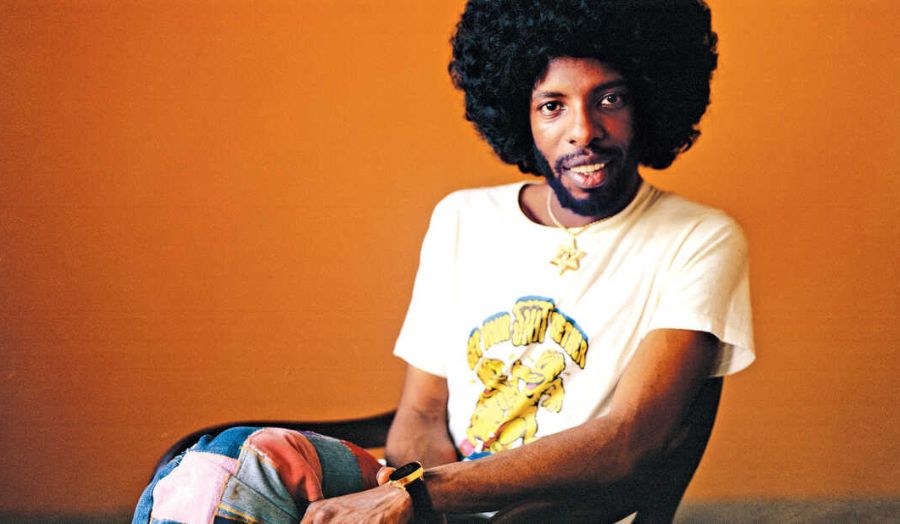

★ or Blackstar was Bowie’s final studio album and much less of a secret; Rolling Stone published a preliminary review of it back in November. “We were listening to a lot of Kendrick Lamar,” Visconti told Rolling Stone of the album. “We wound up with nothing like that, but we loved the fact Kendrick was so open-minded and he didn’t do a straight-up hip-hop record. He threw everything on there, and that’s exactly what we wanted to do. The goal, in many, many ways, was to avoid rock & roll.”

The album’s official release came on January 8, 2016, a Friday. It was Bowie’s 69th birthday, and a handful of GIFs and videos honouring the artist were making the rounds on social media.

Bowie died two days later, on Sunday, January 10, shocking all but his inner circle. Visconti said he knew about Bowie’s liver cancer a year earlier when the artist showed up for a recording session for Blackstar. “He just came fresh from a chemo session, and he had no eyebrows, and he had no hair on his head,” Visconti told Rolling Stone on January 13, “and there was no way he could keep it a secret from the band. But he told me privately, and I really got choked up when we sat face to face talking about it.”

Visconti said he spoke with Bowie via FaceTime a week before his death, and Bowie talked about a few new demos he had on hand for a follow-up album to Blackstar. “And I was thrilled,” Visconti continued, “and I thought, and he thought, that he’d have a few months, at least. Obviously, if he’s excited about doing his next album, he must’ve thought he had a few more months. So the end must’ve been very rapid. I’m not privy to it. I don’t know exactly, but he must’ve taken ill very quickly after that phone call.”

Many of the interviews with Visconti leading up to the release of Blackstar reveal Visconti’s unique perspective on Bowie’s mind and personality. Some also show how much Visconti was learning about Bowie even shortly before his death.

Take this quote from Rolling Stone’s November 2015 preview of Blackstar: “What he gives away is what he writes about. I think a lot of writers feel like, ‘If you want to know about me, just study my lyrics.’ That’s why he doesn’t give interviews.” Visconti said, answering a question he couldn’t just two years prior. “He’s revealed plenty in past interviews, but I think his life now is about his art. It’s totally about what he’s doing now.”

Or this one, from a January edition of The Sun: “He’s obviously a much happier man now and he’s really much more solid as a human being. He doesn’t practise any of those indulgences that he did in the seventies. None of us do. We’d be dead.”

Or this, from the January 8 Los Angeles Times, published just two days before Bowie’s death: “He comes prepared now. This is an old dog with new tricks. Now, by not announcing he’s making a record, he gives himself the time to be creative. Playing saxophone on these demos, bringing in radical guitar parts. He really is making music for himself these days. There’s no fluff about David Bowie anymore. There never was, really.

* Tony Visconti to Rolling Stone (1/13/2016)