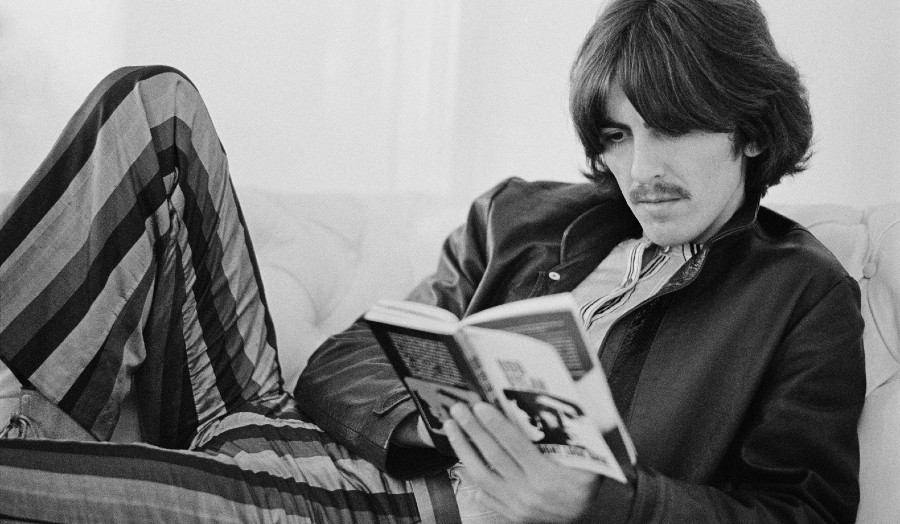

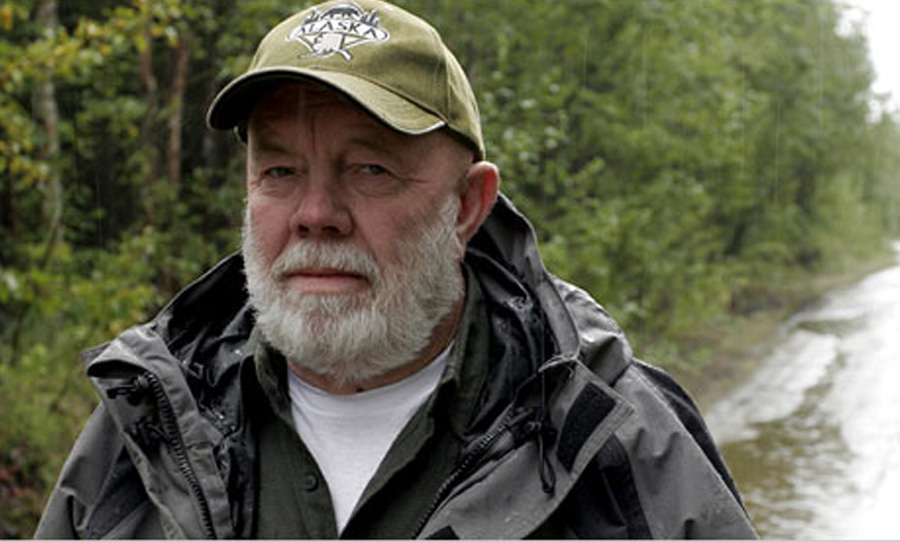

Gary Paulsen’s childhood memoir Gone to the Woods speaks to his audience with vividness and brims with his unique poetic voice.

In the domain of childhood literature, Gary Paulsen is colossal, possibly the biggest ever. With an astonishing 200 books to his credit, he’s won the Newbery Honor three times — childhood literature’s equivalent of the Booker Prize.

He knows how to speak to kids. And as you might expect, this preternatural ability was forged in his own childhood. Gone to the Woods [Pan Macmillan] is the story of this period of his life. Rendered in a poetic style that is fundamentally unique to him, it reflects the adventurousness of his oeuvre, but also sheds light on the fissures that punctuated his early years.

Gary Paulsen’s infancy was spent with his mother in wartime Chicago. While she made ends meet working in a “munitions plant making twenty-millimetre cannon shells.” She drank, she partied, she found companionship in a laundry list of men who were strangers to the young Gary.

Now imagine this: to escape the debauchery of his surrounds the five-year-old was summoned to live with his Aunt Edy and Uncle Sig in the wilds of Minnesota. He would make the journey of some 800 miles via train, by himself:

“His mother took him to the station in Chicago, carrying his small cardboard suitcase. She pinned a note to the chest of his faded corduroy jacket scribbled with his name and destination, shoved a five-dollar bill in his pocket, hugged him briefly, and handed him over to a conductor.”

As you can glean from the quote above, the memoir is written from the third-person perspective. Rather than following Paulsen as a child, the reader is presented with ‘the boy’ instead. And though we can only speculate at his reasoning, in effect, this device draws encourages the reader to interpret Paulsen as a fictionalised character and fill in the blanks, as it were.

The boy’s train adventure is a mere appetiser for an oncoming era of forced independence. But it’s also a period of immense growth and nurturing. Thrown in the deep end, it’s exhilarating to witness how kindergarten-aged Paulsen takes to his work on the farm, overcoming incredible challenges, all the while forming his lifelong affinity with the rhythms of nature.

Trials and tribulations return to shatter this idyll. Forced to live in The Philippines with his mother and father, a U.S. Army officer stationed there after the end of World War II, he was left to his own devices.

Upon returning to America, he embarked upon a life — barely an existence — of fringe-dwelling. Shaking down drunks for loose change in the local bar, scrounging around for game in the bush. It’s in these moments in which we find Paulsen’s prose at its idiosyncratic best:

“It was too early to run the bars for change. And it was cold. Blue cold. That’s how he thought of it. Walk with one ear pressed down in the collar of your jacket until the other ear got numb. Then switch ears. Left, right. Numb, flip ears, numb.”

Through happenstance more than anything, he finds another nurturing presence: a librarian who turns him onto books. Broken as the boy is, he still yearned to grow. “…he wanted to see ahead, see what was over the next hill,” Paulsen writes of his adolescent self, “and when he saw what was there, he wanted to keep going, see the next and the next and the next.”

The hallmarks of Paulsen’s style, his directness, his flair for adventure, his complete lack of pretension, is reflected in his memoir. Nowadays, Paulsen continues to live well away from urban centres, but not on the fringes. Instead, he’s shared his gift with the world. Gone to the Woods traces the journey of what could have been a tragedy, but in the end, became a triumph.

Gone to the Woods is out now via Pan Macmillan.