The 1970s was a phenomenally important decade that lead to the world we have today – from the first video game consoles and tabletop computers, to fuel crises that gave us the modern automotive landscape.

The 1970s was also a landmark period for music, from the launch of the Technics SL 1200 in 1972, to the Fairlight CMI by the end of that decade and the breakup of both The Beatles and The Doors, bringing an end to the ‘flower power’ psychedelia that was the hallmark of the previous decade.

A multitude of influential bands and artists, as well as recording and production techniques that are familiar to many in the industry today were first realised in the decade that gave us safari suits, Countdown and fondue parties.

Some of the bands that were the biggest in this critical era had their roots in the 60s – Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of The Moon and The Rolling Stones Exile on Main St could be their most loved (by critics and fans alike) albums, and they were products of the 70s.

Yet this story isn’t about a particular band, artist or trend – this is a story about the paradigms sought out by those bands already mentioned and others like them, to explore what is possible in music.

From the breaking down of musical trends to quantum leaps in technology, the 70s had it all. We take a look at an era that paved the way for modern music production.

The studio as an instrument

While the ancestors of modern synths such as the Mellotron were developed in the 1960s, transistorised technology was only just taking off, with the most recognisable Moog models coming onto the market starting in about 1972. Some early users of synths, were bands such as Pink Floyd, where the otherworldly pulse that you hear in On The Run from Dark Side of the Moon – bends your mind thanks to the Moog.

To focus on how significant the 1970s was to the music we have today, a single song comes to mind: 10cc’s I’m Not in Love from their album The Original Soundtrack (Mercury Records, 1975). This song was notable for its innovative use of not only synths and keyboards, but also from a production standpoint. This is because the soaring ‘choir’ that you hear in the background was cobbled together in a very intelligent way, using the entire chromatic scale and a 16 track mixing desk.

This painstaking process was fulfilled by each member of the quartet singing one note on the chromatic scale multiple times, and eventually arriving at the lush ‘wall of sound’ with a massive 256 voices!

While the song does feature conventional instruments, such as bass, guitar and drums – it’s the clever use of multitrack recorders and unconventional production such as the sound of a music box, providing a falling, ethereal close to the six minute track, or the whisper of “Be quiet, Big boys don’t cry” from the studio’s secretary, while the drum at the start of the track fulfills the role of the song’s heartbeat.

All of these reasons cemented I’m Not in Love as a significant title when it comes to studio innovation, with the mixing desk being used as an instrument, years before the sampler in order to create the abundance of layers that you hear on the record. This lush epic has maintained enough freshness to have been included in 2014’s Guardians of the Galaxy, rekindling interest in the track.

The digital revolution

Another important innovation during the 1970s was the development and utilisation of digital technology. Once such band to embrace this innovative way to produce sound was Joy Division, in the recording of their seminal album Unknown Pleasures (Factory Records, 1979). During the tracking of the album, the band used the pioneering AMS Stereo Digital Delay, which was released in 1978.

The AMS 15-80S, to give it its official name, is a rackmount effects unit that is used to add delay to any signal passed through it, allowing the user to determine how many milliseconds of delay they desired and was accordingly, adjustable. It was used extensively on Joy Division’s debut, produced by Martin Hannett.

The machine produces a ghostly sound, and its contribution to the tonal atmosphere of Unknown Pleasures cannot be underestimated. Along with other effects that Hannett used on the band’s records, the AMS Delay was undoubtedly essential to Joy Division’s cold and distant sonic identity.

In fact, by the end of the decade, digital technology had managed to infiltrate the music making process from beginning to end – or from creation to consumption. The manipulation of tones via synthesis was hitherto an analog pursuit. In 1975 however, the first digital synthesiser, the Synclavier was built by Sydney Alonso and Cameron Jones. Commanding price tags north of $75,000, this was no bedroom instrument. Yet, it found homes with the likes of Stevie Wonder, Frank Zappa and Sting among others.

Even more than the sounds they produced, inventions like the Synclavier and the Fairlight CMI were harbingers of a contemporary studio workflow. In digital terms, today’s DAW based systems are several generations removed from the predominantly analog realm of the 70s studio. The essential components of what we take for granted in our modern setups – digital sampling, hard disk recording, seamless sound editing – were all pioneered in the heady days of this conspicuous epoch.

As we move down the production line from music performance, we begin to encounter digital recording systems. The 3M Digital Audio Mastering System began tracking in the late 70s, but at a cost of over $100,000, was still a thoroughly professional tool. The PCM-1 by Sony further democratised digital recording and was the first commercially available analog-digital and digital-analog converter, a piece of technology inherent in every audio interface today.

The PCM-1 was originally a 14-bit system, but would eventually become record with 16-bit resolution. Why? It would have to comply with the next revolution in the consumption of music: the compact disc – the format that would dominate the industry for the next two decades or more. So the life cycle of production, recording and product was encircled by digital innovation. Although digital methods of music production weren’t yet completely dominant by the dawn of the 80s, the technological leaps of the 70s would lay down the blueprint for studio practice as we currently know it.

How disco changed the music scene

When people think of the 1970s, one of the things they tend to picture in their heads is John Travolta in a polyester suit, strutting around a lit dance floor to the tones of the Bee Gees in Saturday Night Fever. While this is seen as a factor in the popularisation of disco itself, this 1977 film was also a catalyst in the downfall of the genre by the end of the decade – culminating in the Disco Demolition Night at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on 12 July 1979. So where did all this start, and how is it sonically significant?

Disco can trace its stylistic origins to R&B, soul and funk from the late 1960s. Famous labels that had disco outfits on them were primarily based in New York City, and included ones such as Salsoul Records, Atlantic and Prelude Records to name a few.

Disco (and its post-demolition incarnation, post-disco) was innovative insofar as the use of classical musical instruments and ornate production, such as Bebu Silvetti’s Spring Rain (Salsoul, 1975) or MSFB’s Love is the Message (Philadelphia International Records, 1973). Not only that, but the multilayered arrangement of both of these also included the use instruments such as the Fender Rhodes piano, adding to the depth and density of the mix.

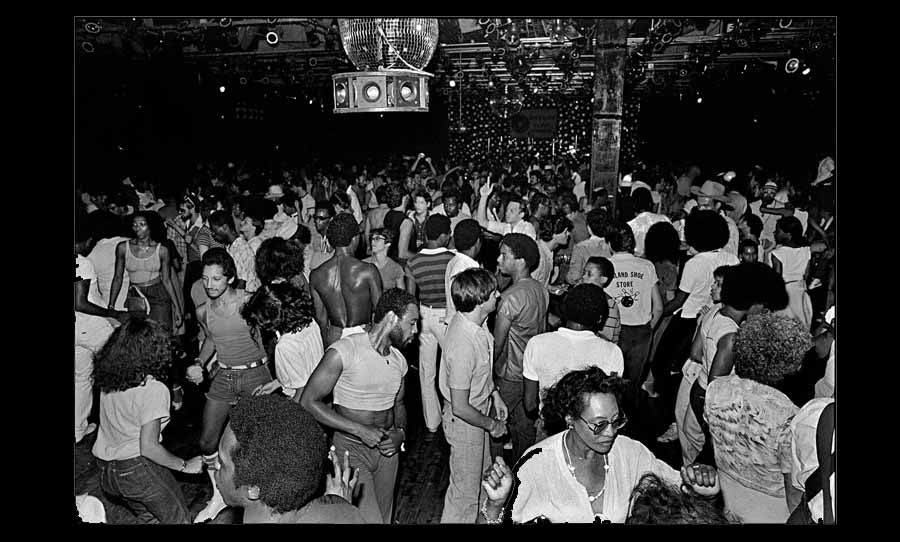

Aside from the opulent studio productions of these hits, disco also revolutionised the way people experienced music in social settings. In 2016, a consequential figure in the development of Disco music (and subsequently house music) passed away. David Mancuso helped to popularise the big, dancefloor grooves that disco is famous for with his parties at a New York loft in the early 70s.

According to Tim Lawrence’s Love Saves the Day (Duke Uni Press, 2003), Mancuso’s set up for the loft propagated the sound of disco music itself due to the large Klipsch speakers that he wanted for his post-counterculture, free of charge parties – in its own right, an important development that contributed to the sound of disco: is its ability to fill a room with sound. Mancuso continued to experiment, using two Philips turntables without a mixer (something inconceivable today!), and JBL tweeters to augment the listening experience.

Later in the decade, after the events of Disco Demolition Night, the genre experienced a mainstream decline and was brought back underground, thanks to the exploits of Larry Levan, Frankie Knuckles and many more in the New York disco scene at the end of the 1970s.

Levan’s brainchild, the Paradise Garage, was made from a converted parking garage, opening in 1978. One of the biggest sonic contributions was the addition of two giant 500W speakers with enclosures in a W shape, nicknamed the ‘Levan Horns’, constructed from Jensen-derived speakers and the aforementioned JBL tweeters.

The sort of tracks that were played at the Garage defied conventions of what disco music was in the popular sense. Aside from playing the tracks aforementioned, the Garage was the sort of place where you heard cutting-edge electronic music, especially as the 80s dawned – from artists like Thelma Houston, Chic and countless more – with a glossy, synth-driven and simultaneously bass heavy sound.

The 1970s, while a decade shaped by questionable fashion choices and war in Vietnam, was a groundbreaking decade for music that continues to resonate. Covering all musical innovations of the 70s is a herculean task, but just a narrow glimpse reveals a richness of diversity in production and progress in audio technique.

From old rockers shedding their hippie psychedelia in favour of a grittier, bluesy sound, through to the electronic futurism of acts such as Gary Numan and the fuzzed-out experimentation of bands like Pink Floyd – the decade featured several evolutionary leaps in music production. This was thanks to the work that not only gave us smaller, more powerful electronic instruments – but also the sounds and aesthetics that musicians, engineers and producers have drawn on for inspiration since.