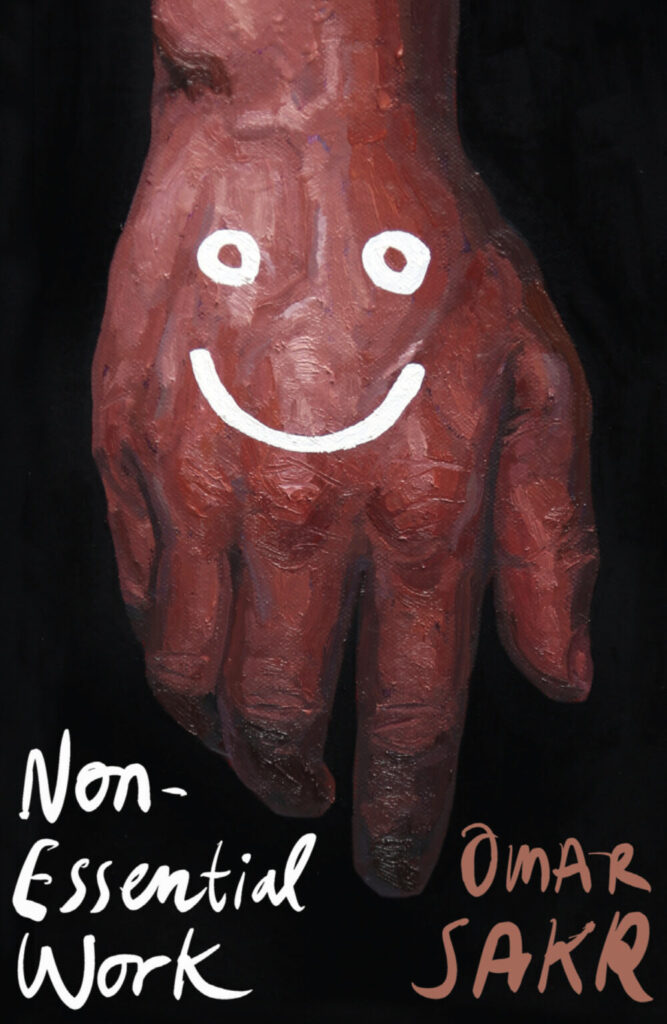

In his latest collection Non-Essential Work, Omar Sakr crafts hauntingly beautiful verses that explore themes of grief, displacement, and the enduring power of language.

In the world of poetry, Omar Sakr is a force to be reckoned with. The Australian-Lebanese poet, author, and editor has been making waves in the literary scene for years, his debut novel “Son of Sin,” released last year, received critical acclaim and was praised for its raw, honest, and evocative exploration of themes such as masculinity, identity, and the immigrant experience, and his latest collection, Non-Essential Work (UQP), is no exception.

With themes of love and loss woven throughout the pages, Sakr’s poetic language and form create a distinctive voice and aesthetic that sets him apart from the crowd. From sapphic stanzas to anagram poetics, Sakr fearlessly experiments with form, all the while grappling with the relentless nature of trauma and the power of language to express it.

We sat down with Omar to discuss everything from his writing process to his suburban woes, all the while reminding us that the enduring value of art is ultimately in the hands of its audience. With Non-Essential Work, Sakr has crafted a collection that speaks not only to the present moment, but to the very heart of what it means to be human.

Happy: What are you up to today?

Omar: My wife and I work from home, and we alternate primary care for our son. Tuesdays are my work day, but today is a little unusual for me—it’s the release day for my new book, so I went to Newtown to visit Better Read Than Dead and sign some stock. I’ve been in the social media mines since then, promoting it. Most of today will be spent doing admin and promotional work.

Happy: Tell us about your suburb, what do you love/not love about where you live?

Omar: I live in Auburn, and I love how close I am to the beautiful Gallipoli Mosque, I love how at home I feel here; I do not love that seemingly everyone smokes here, and nobody seems to care about the ‘no smoking’ signs. It’s particularly frustrating to me as a parent, because I can’t even take my boy out without have to walk him through a toxic cloud.

Happy: How has your writing evolved over time, and what do you see as the key themes and ideas that run through your work?

Omar: I’ve settled into myself, into my voice, and my writing is more assured, more precise than before. Grief is my world, and my work is finding the language to express it: the dislocation of the heart.

Happy: Your new collection, Non-Essential Work, explores themes of love and loss. What inspired you to delve into these topics, and what do you hope readers take away from your poetry?

Omar: In many ways this book springs from the word “relevant” that was continually pinned to my writing as a marker of its value. I wanted to question that value, to dig into each day and shake it until its images and ideas fell out of the prison of its date. From there I fell into everything else.

Happy: How do you balance the desire to capture the present moment with the desire to create something enduring?

Omar: Look, every writer is a maniac with control issues, but at some point, we have to let go and realise that whatever endurance a work has is decided by the audience and not us. Personally, my focus is on creating art that has the ability and power to work its magic principally on myself, first, and then whoever happens to be alive today—to hell with tomorrow, tomorrow is a problem for its artists.

Happy: How does the collection use poetic language and form to create a distinctive voice and aesthetic, and what role do rhythm, sound, and imagery play in shaping the poems?

Omar: I don’t normally engage with forms, but this collection is a departure in that sense—focused as it is so much on grief and the repetitive, relentless nature of trauma, I turned to the constraints of forms like Jericho Brown’s Duplex, and Marwa Helal’s The Arabic, as well as American sonnets, sapphic stanzas, hell I have even a sestina in there and I hate sestinas usually. I used mirror forms, iambic pentameter, and anagram poetics, in addition to the lyric free verse and prose poems you might expect from me.

All of it is reflective of my hopeless attempt to escape the trap of language, to turn it inside out, to circle obsessively what animates me most: love, of course, and loss.

Happy: As someone who has lived and worked across multiple genres, including poetry, fiction, and essays, how do you navigate the boundaries between different forms of writing?

Omar: I mean… the boundaries are there, irrespective of me. I can choose to obey them or not, like anyone else. I’m a full-time writer, so I’m often writing to commission or with a specific publication in mind. This means I set out from the beginning knowing the form of what I’m writing. Outside of that context, when I’m just dreaming up new things, though, I will say that poems are always poems, I never have an urge to make a poem anything other than what it is, whereas the other two can sometimes change places.

Happy: How do you approach writing about your own experiences, and what challenges or opportunities does this present?

Omar: I don’t! My experiences approach me, they bash me over the head, they demand to be articulated or else drown me, and so I write. I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again: whatever I imagine is also my experience, it is not separate. For me as a writer, the challenge posed by the ‘fictional’ and ‘real’ is the same: to create compelling literature that resonates with the music of the world and with other people.

Happy: And lastly what makes you happy?

Omar: My beloveds, of course, my wife, my child, my queer family; drag queens; faggotry in general, blessed be; trash TV; reading science fiction and fantasy; having enough money to live.

Non-Essential Work is available now via all good book sellers.