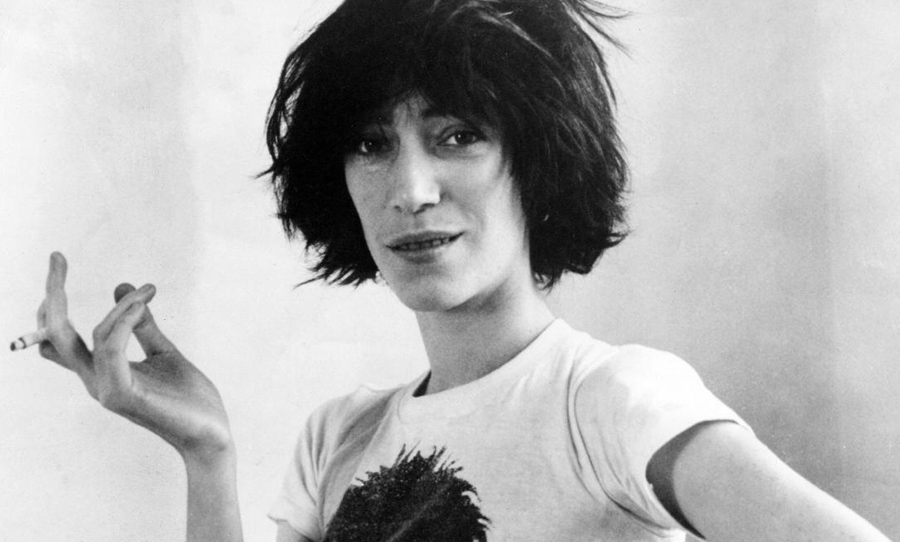

In the ’70s, New York was a crucible of musical style. Let’s take a look at one of the seminal albums of this time and place: Horses by Patti Smith.

With the establishment of the ’27 club’ at the beginning of the 1970s (the untimely deaths of Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix) new movements in music would begin to fill the void left behind by those losses, and the breakup of The Beatles in 1970.

The city to provide these new sounds was New York, which by 1975 had started to develop two distinct styles — punk and disco (later, it would also birth hip hop). The former is where Horses, Patti Smith‘s groundbreaking record, is situated.

Recorded at Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios and produced by ex-Velvet Underground founding member John Cale, Horses was Patti Smith’s debut and was released at the end of 1975 to critical acclaim with Arista Records. The studio wasn’t purpose-built for the task of recording. In fact, it was an old nightclub that Jimi Hendrix and his manager purchased in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1968.

Eddie Kramer, the engineer responsible for most of Hendrix’s output up to that point, described the space to Mix, saying that it was “not huge…the ceiling drops to 13 feet at one end, and is 16 to 17 feet at the other. But it sounded good…” Another interesting aspect of Electric Lady’s original studio is the gear used at the time. In the same interview, Kramer describes the debacle around the studio’s Datamix console:

“…The console builder was in over his head…it was unbelievably badly made…we literally had to rebuild the console, and it took two or three months to rebuild the console.”

Aside from the studio’s console (a custom build that also utilised API faders), the tape machine also bears mentioning. Kramer chose an Ampex MM-1000 tape machine as a complement to the studio’s smaller 2 and 4 track tape machines. The 16-track machine was wired for 24, which was later converted according to Kramer.

With the custom console and the modified Ampex tape machine in a subterranean environment, producer John Cale and band members Patti Smith, drummer Jay Dee Daugherty, guitarists Lenny Kay and Ivan Kral, and Richard Sohl on keyboards came together to put the material that would make Horses together.

While recording the album at Electric Lady Studios was Smith’s tribute to Hendrix, her friend and idol, the choice of producer was intended to recreate the band’s live sound in the studio. Smith’s decision to tap John Cale was completely arbitrary.

Initially, the producer and the artist wanted to push Horses in the same direction as the Beach Boys 1966 magnum opus, Pet Sounds — that is, multi-tracked and complex layering of instruments — but the single-mindedness of both Smith and Cale’s approach toward the ‘ideal’ record (the producer wanted to replace the guitarists’ battered instruments, for example) differed quite markedly.

Speaking to Rolling Stone in 1976, she related her experience with John Cale, lamenting that “all I was really looking for was a technical person. Instead, all I got was a total manic artist. I went to pick out an expensive watercolour painting and instead all I got was a mirror.”

This manic tension in the studio lead to Patti Smith distancing herself several months later from Cale’s work, telling Salon that it had been “spewed from my womb…it’s a naked record” — her way of highlighting the creative frustration with Cale.

Yet Cale’s affinity for working with female vocalists (having produced several of former bandmate Nico’s solo albums) had eventually worked its magic on the band, where they extended and improvised the songs, culminating in a nine-minute version of Birdland.

Widely considered the first ‘art punk’ record, Horses walks this line by combining rawness with sophisticated studio work. With engineering courtesy of Bernie Kirsh and guitar from Tom Verlaine of Television — the album’s underground aesthetic couldn’t be more appropriate, helped in part thanks to the beat poetry influenced lyrics, inspired by William Burroughs, among others.

The album’s opening track, Gloria: In Excelsis Deo, is a cover of the 1960s Van Morrison classic but recast as a marker for the forthcoming punk rock movement. The song opens with the memorable line “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine” accompanied by piano and guitar chords.

It follows the conviction that John Cale set out while working with the band: extending and improvising the song with improvised poetry which throws Gloria’s lyrical/sexual message into question. Supported by Kral and Kay’s guitar work, it took Van Morrison and Them’s Gloria, into a completely new sonic direction combined with frenetic improvised poetry.

The album then takes a less aggressive instrumental turn, with tracks like Redondo Beach and Birdland. With these tracks, poetry is explored, alongside two stylistic motifs; reggae and jazz. In the case of the latter, the themes of Birdland deal with death and transcendence, from the perspective of a boy and the alien relationship he has with his father — in this case, literally.

This comes from the line “No, daddy, don’t leave me here alone/ Take me up to the belly of your ship”. Both this track and Redondo Beach deal with themes of death, but the upbeat tempo and instrumentation of the album’s second track belies the dark theme. But where the story speaks of suicide, especially in the chorus, it becomes clear:

“Down by the ocean, it was so dismal/Women all standing with shock on their faces/ Sad description, oh I was looking for you.”

While side 1 of Horses deals with themes of sex and death, the opening track to side two, Free Money is a song referencing Smith’s time when she was growing up poor in southern New Jersey. With instrumental work and a ferocity that not only colours the rest of the album, the lyrics also point to that period in Smith’s life. It’s especially evident with the opening line:

“Every night before I go to sleep/Find a ticket, win the lottery/scoop the pearls up from the sea/cash them in and buy all the things you need”

While Free Money is about her experiences growing up, Kimberly is about family — specifically Smith’s little sister. The instrumental makeup of this track is in keeping with the traditions of rock, but the snare drum and bass guitar are in the front of the mix, while the electric guitar is playing second fiddle.

The album’s third-to-last track, Break it Up was written by Smith about one of her idols, the late Jim Morrison of The Doors. Written with the help of Tom Verlaine (who also contributed guitar for this track), it references mythology, among other things, and was inspired by a dream where Patti thought that Jim Morrison, bound like Prometheus, broke free with wings from a marble slab. Verlaine’s anguished guitar underscores the dramatic imagery provided by the lyrics.

The penultimate track in Horses, the epic Land: Horses/Land of a Thousand Dances, is a ten-minute romp into a psychedelic world where the protagonist, ‘Johnny’, is raped (The boy took Johnny, he pushed him against the locker/He drove it in, he drove it home, he drove it deep within Johnny), becomes addicted to cocaine (where ‘ white horses’ is mentioned, it is thought as a stand-in for drugs, as a nod to William S. Burroughs).

The final track, Elegie, is a memorial to Patti’s friend Jimi Hendrix, and the mournful application of piano and guitar underscore this, like ghostly wails from the void. The reference to Hendrix appears from a line lifted from Are You Experienced?, in the form of:

“Trumpets, Violins, I hear them in the distance”.

The final song was recorded live in the studio on the final day of recording, September 18, 1975; five years to the day that Hendrix died at the age of 27.

Patti Smith’s Horses has consistently been seen as one of the most significant recordings of the punk era, pipping The Ramones’ eponymous album by four months. But the record is more than just punk; the album blends themes of family, death, sex and drugs, delivered by a vocalist whose cold stare from the cover — just like its contents — is eternally enigmatic.