South Asian representation has historically been limited in Hollywood by Orientalist caricatures. But there finally seems to be a change in the air.

Hollywood’s problem with inclusive representation is no secret. Historically rife with stereotypes, portrayals of minorities have been consistently reductive. The South Asian community has often been excluded, if not erased, from nuanced character portrayals in Western cinema.

As a result of this, South Asians have been dehumanised, even desexualised, in the roles we see on screen. White-washed, Orientalist perceptions of the community have been prevalent in cinema for decades.

Why does it matter?

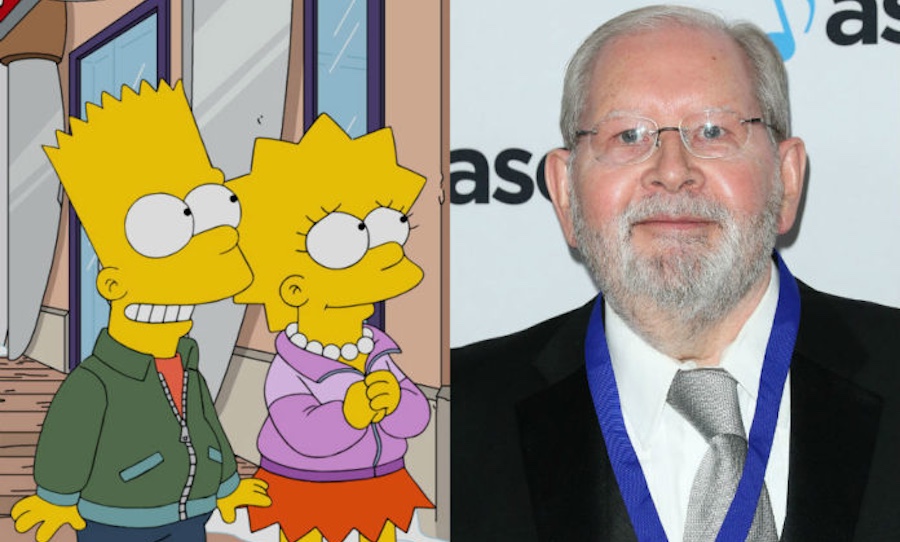

Essentially, Hollywood stereotypes are hugely problematic. If we focus on masculinity, South Asian men in Western society are depicted within a few key clichés. There’s Apu Nahasapeemapetilon from The Simpsons, whose characteristic sing-song, broken English — voiced by the very-white Hank Azaria — was one of the longest-running depictions of immigrant South Asian families on TV, and was a “[reflection] on how America viewed [South Asian immigrants]: servile, devious, goofy,” according to comedian Hari Kondabolu.

In the same vein, there’s also the caricatured narrative of the socially awkward, sexually repressed Raj Koothrappali from The Big Bang Theory.

Late to this but I’ve dealt with my share of Indian-bashing via the Apu character and to have the Simpsons dismiss it via Lisa is trash. Plain and simple. Time change, learn and grow. Don’t dig in to justify dumb stereotypes.

— Neera Tanden (@neeratanden) April 12, 2018

Both characters are examples of South Asian identity being used as a comedic punchline; a tokenistic representation that strips the characters — and an entire community — of a sense of identity. In Kondabolu’s documentary The Problem With Apu, several high-profile South Asian-American actors admitted that they had been asked to perform roles in the “style and voice” of Apu, despite their experience as trained actors.

Their experiences show that this type of representation can have a huge impact on the roles that are written for South Asian men, and continue the cycle of emasculated and exotified representation that we see on screen.

The hate that Hari Kondabolu gets pisses me off so much. If you watch his film, it’s clear that he loves the Simpsons and Apu, but has a complicated personal relationship with the effect the character had on his life.

— Kieran (@KingImpulse) October 28, 2018

Another example of questionable representation is Max Mighella’s role as American-Indian businessman Divya Narendra in the Oscar-nominated film The Social Network. Minghella is a British actor of Chinese and European descent. There really isn’t much else to be said on how problematic this type of erasure is, but just to clarify: they didn’t replace Narendra’s character, but intentionally cast a person of completely different ethnicity in the place of a South Asian.

If we consider the power held by production houses and executives, it raises an interesting question — why had South Asian identity been so alienated that it lost all relevance to Hollywood?

Max Minghella getting darker make up in the Social Network to play an Indian character pic.twitter.com/ak7V2elpek

— Irfan Damani (@DamaniIrfan) July 4, 2019

In short, meaningful portrayals of South Asians had historically been tossed aside by Hollywood. It goes without saying that the implications of such cavalier behaviour towards representation have the power to be destructive. Some may argue that “destructive” is an exaggerated term, but as part of the South Asian diaspora… I cannot see it any other way. Cinema holds the power to shape the way that members of the Brown community see themselves, as well as the way they are seen by others.

Many South Asians from the diaspora — including myself — have had a complex relationship with our identities. And while I acknowledge my position as a woman mostly writing about portrayals of masculinity, it is undeniable that the experience of internalised racism is genderless within our community.

The New Wave

Despite this, there’s a reason for optimism. Recently, there’s been a distinct surge in South Asian writers, directors, actors, musicians, showing that young South Asians are radically reconstructing what it means to be “Brown” in Hollywood.

First-generation South Asians like Mindy Kaling and Aziz Ansari both created, and starred in major TV productions in the 2010s, The Mindy Project; Never Have I Ever; The Sex Lives of College Girls, and Master of None, respectively, with Kaling starring in multiple Hollywood blockbusters (A Wrinkle in Time and Ocean’s 8); comedian Hasan Minhaj headlined the White House Correspondents’ dinner in 2017 and hosted the late-night talk show The Patriot Act; Bollywood star Priyanka Chopra’s starred as an FBI agent in Quantico from 2015-18; Spin’s Avantika Vandanapu is positioned as the first Indian-American lead in a Disney Channel film; Sex Education’s Simone Ashley is slated to lead the incoming season of Bridgerton.

mindy kaling cinematic universe edit never have i ever four weddings and a funeral the office the mindy project a wrinkle in time ocean’s 8 late night pic.twitter.com/vwj4mjoAQM

— ゚ ✩ 。࿐ ・ 。゚ (@sanktaamita) September 18, 2021

All these artists — and many more — are reinventing what it means to be young, Brown, and in complete control of your cultural, social, and sexual identity. The Mindy Project’s eponymous Mindy is a sexually active, complex comedic character, Master of None’s Dev quietly, yet fundamentally, investigates his hyphenated identity living in the West, and Never Have I Ever’s Devi defies the “nerdy” Indian girl trope and explores her teenage sexual identity.

And while South Asians have steadily begun to make their mark on TV, there’s been a similar air of change in cinema as well. But before we get into that, it’s worth mentioning that there is a gendered nature to this wave of representation. Movies like The Big Sick and shows like the aforementioned Master of None, often elevate Brown male sexuality by using Brown women as one-off plot lines to diversify their eventual end goal: to end up with a white woman.

Now, let me be clear: there is absolutely nothing wrong with interracial relationships. But in terms of representation and cinema, the issue arises when male POC narratives are written to justify dating/marrying outside the culture by disparaging the women of their own culture. It’s an aspiration to whiteness — conveyed through jokes, laughs, comments, etc. — that is ironically reflective of the exact same representation issues faced by male POC that we discussed earlier.

A Reimagining of the South Asian Leading Man

While film roles for South Asian men have historically been limited to comedic, side-kick characters, there have been two recent notable exceptions to this rule: The Sound of Metal and The Green Knight. In my short life, they’re perhaps the first two roles I’ve seen that don’t engage with emasculated ethnic stereotypes, despite the lead actors’ South Asian heritage.

Sure, while both the lead characters are not written to be of South Asian descent — and despite the fact that I am a firm believer that South Asian ethnic identity still deserves appropriate representation on screen — it’s an aspect of both films that struck me as unique.

In The Green Knight, the dynamic between the Arthurian source material of the film and leading man Dev Patel’s British-Asian identity is a refreshing creative decision. It subverts the age-old Hollywood tradition of centering whiteness in cinema, allowing the audience to experience a world where a Brown man is a hero. In particular, the lead hero Gawain.

For those who don’t know, Gawain is the nephew of King Arthur and a joyously intricate character in the Arthurian legend. It’s an awesome instance of positive representation, where South Asian men are afforded the complexities of masculinity – including the joys and tribulations that come with it.

like on one hand it is kind of weird how everyone has latched onto dev patel as the Token Hot Guy Of Color Of The Month but also i’ve spent my whole life hearing about how indian guys are gross/disgusting/sex obsessed/etc so it is nice to have some positive representation

— cam (@caffeinecrawls) September 18, 2021

Wanna watch the green knight again just to look in awe at dev patel

— 🔪 (@Iuvmako) September 14, 2021

Next, is the Oscar-nominated drama The Sound of Metal, which stars British-Pakistani creative Riz Ahmed. Playing the protagonist Ruben, the role saw Ahmed become the first Muslim actor to be nominated for Best Actor at the Academy Awards, amongst several other nominations that included Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay. The narrative follows the life of Ruben, a talented young drummer who loses his hearing and attempts to navigate a new sense of identity.

Beyond its critical representation of the d/Deaf community, one of the most stunning aspects of Ruben/Ahmed’s depiction is when he’s presented in the opening shot as topless, visually drenched in magnetic sex appeal. It’s a scene not commonly associated with South Asian men in Hollywood. As a former heroin addict and a deaf drummer, Ahmed’s character is infinitely complex and allows the image of a Brown man to possess sexuality, whilst also holding a vulnerable, emotional identity.

The images of Patel and Ahmed may not seem significant to some, but for a community that has been mostly ruled by stereotypes in cinema, it’s reassuring to see a visual of a South Asian being afforded a complex identity, whilst simultaneously being at the center of a Hollywood movie.

The critical and commercial successes of both The Green Knight and The Sound of Metal further prove the excellence that can arise when Brown actors are given the chance to break free of the constraints of the stereotype-riddled, trivial roles that Hollywood has given them in the past.

Riz Ahmed is so hot I can smell this picture. pic.twitter.com/AVeMioHe84

— Joel Kim Booster (@ihatejoelkim) December 22, 2020

Lastly, in the case of historical representation like Apu, it’s never been about being “able to take a joke.” Many people in our community have had valid experiences of trauma that correlate with the way our culture has been caricatured by white creators on screen.

With The Green Knight and Sound of Metal, it finally feels like a step in the right direction. While the progress is slow, respectful and inclusive representation seems to be taking the front seat in many productions coming out of America, and South Asian creatives are rightfully reclaiming their cultural identities. We, and all other minorities, deserve the chance to be represented as the complex, diverse human beings that we are — and it seems like Hollywood’s beginning to catch on.